The Fraud of the Century

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2024

- Creators

- Paul Nelson

- Topics

By Paul Nelson

A chance meeting in the Ramsey County jail in early 1923 led to one of the longest criminal trials in St. Paul history. The story that unfolded there—slowly, very slowly—had the elements of a nineteenth-century novel, or maybe a farce, or even an opera: a hapless (or conniving) widow; a venal (or impossibly clueless) public official; a cynical con man (or a big dreamer in over his head); ethnic pride exploited; life savings ravaged; backs stabbed; and (probably) justice finally served. It’s no wonder that, on some days of trial, spectators would not leave their seats for fear of losing them. The Daily News called it “perhaps the most spectacular case in the history of the courts of the northwest.”

When Criminals Connive

It all began in jail, and, in due time, ended behind bars—again. Clarence Cochran and Ed Ritter were salesmen (or crooks), there on bad check charges. Arthur Lorenz, managing editor of St. Paul’s German-language newspaper, Die Volkszeitung, was held there on arrest warrants for criminal libel in Illinois. In the pages of the Illinois Staats-Zeitung, he had written in December 1921 that the American Legion consisted of “the refuse of the nation” and a bunch of “. . . tramps, vagabonds, and bums . . .” It might have been Lorenz’s first turn behind bars, but Ritter and Cochran were veterans of the calaboose. Both had been arrested twice in 1922—once for possession of bonds stolen in a New York City mail robbery and again for cashing a worthless $3,618.50 check. In jail, Cochran and Lorenz got to talking.

Clara Bergmeier of St. Paul had inherited the Volkszeitung Publishing Company from her husband, Frederick William, when he died in 1905. The newspaper had once thrived, but World War I hit it hard. In 1917, the United States, on orders of Pres. Woodrow Wilson, had interned its editor (Bergmeier’s brother-in-law, Fritz) as an enemy alien. Then, the state canceled its printing business with the company. And, of course, German immigration to the United States was suspended by the war.

By 1923, Die Volkszeitung’s circulation was fading, debt was mounting, and Mrs. Bergmeier, at sixty-one, was looking for a way out. She had tried to sell the paper to German American buyers, but her asking price—$100,000—was not met. To raise cash, she resorted to selling stock in the corporation. On advice from Lorenz, she also hired Lorenz’s former cellmate Cochran, first as circulation manager, then to help sell stock.

Takeover Troubles

Within weeks, Cochran had taken over the sales operation; within months, he owned the company. Bergmeier had found no buyers for it at $100,000, but Cochran contracted to acquire it for $150,000. He procured an inflated appraisal of its real estate (Volkszeitung Publishing owned the building at Third and Jackson) then used that appraisal to justify issuing corporate notes and bonds (supposedly secured by the real estate), which he peddled to investors. For Cochran, Volkszeitung’s greatest asset was not its publishing business or its building; it was its subscriber list—16,000 names of mostly aging and thrifty German Americans. That’s where he had gone to find the money he promised Bergmeier (he had none of his own) until stopped by state regulators.

The resourceful Cochran then made a pivot. Bergmeier had been treated at, and later invested in, the Minneapolis Sanitarium Hotel. This outfit claimed to use an effective treatment for diabetes (one of its local innovations was implanting sheep glands in humans) and needed more space. However, it had run out of money to enlarge its facility on Harmon Place. Cochran created the Loring Holding Company, bought the hospital, secured a fanciful appraisal showing an inflated value, and set about raising cash by selling notes and bonds. Loring Holding Company authorized selling up to $2,000,000 in bonds based on assets generously valued at about $275,000. Cochran’s sales team neglected to tell people that a Minneapolis city ordinance forbade locating a hospital within 1,000 feet of a park. Loring Park stood across the street.

All of Cochran’s securities promised to earn 7 percent annual interest, with payment in gold coin. Thus, they were “gold notes” and “gold bonds,” supposedly secured by mortgages on the various real estate holdings. Gold, with its ancient allure of mysterious intrinsic value, has always been attractive to hucksters and their marks. Cochran employed a small army of salesmen across Minnesota and into Wisconsin, the Dakotas, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and as far as Montana.

There were in those days no national securities laws. Minnesota had had a state securities registration statute since 1917—a weak one (violations were only gross misdemeanors) with holes that Cochran mostly tried to exploit. The statute did not apply to short-term notes (less than eighteen months at first, then fourteen months, then twelve), nor to bonds secured by mortgages where the debt did not exceed 70 percent of the value of the mortgaged property. So, Volkszeitung and Loring Holding Company sold short-term notes and made use of their inflated appraisals for selling bonds.

This only partially worked. On August 6, 1924, a Hennepin County grand jury indicted Cochran, Ritter, and six others—who would be their future codefendants in the federal trial—for violating state securities laws in selling Loring Park Holding Company securities. That charge was dismissed on a technicality, but, in 1925, Cochran pled guilty and paid a $900 fine in Washington County for peddling the same securities there. Four months later on December 6, the state securities commission ruled that Loring’s application to sell some preferred stock would likely “work a fraud upon the purchasers thereof.” The commission restricted stock sales to current Loring note and bond holders and demanded a complete financial statement. But nothing slowed Cochran down.

Ponzi Schemes

The disadvantage of bonds and notes, from the seller’s point of view, is that they promise payment; they are IOUs. Stocks, on the other hand, promise nothing. Between November 1923 and July 1926, Cochran incorporated (though he kept his non-German name out of all of them) four brick companies bearing the name Hardstone—makers, he claimed, of a superior brick. When Volkszeitung and Loring gold notes and bonds came due, Cochran’s salesforce induced many investors to take Hardstone stock instead of cash in payment. When investors did get cash (none of it gold coin), it came not from profits but from money cadged from later investors. There was plenty of Ponzi in Clarence Cochran. The head of Cochran’s sales team was the German-born and German-speaking Lorenz.

Minnesota’s 1917 securities law also required that people in the business of selling stock to the public first get a license from the state securities commission. The law required salesmen to be bonded and gave the commission the discretion to reject a license application “. . . for such cause as may to the commission appear sufficient.” The commission had denied licenses to Cochran and his brother in 1922; they were known.

In 1925, Gov. Theodore Christianson appointed Minneapolis banker Andrew E. Nelson state Securities Commissioner for an eighteen-month term effective July 1. In 1926, Nelson presided over the application of Hardstone Brick Company of Little Falls and Hardstone Brick Company of Duluth. Commission staff knew Cochran was the organizer, knew he had been denied a securities license, knew of his various arrests, and knew, of course, of the commission’s recent actions against him in the Loring Holding Company case. At the Hardstone Little Falls hearing, Commission Investigator Ingolf A. Grindeland told Nelson that Cochran was “one of the most crooked promoters ever.” Some investors in Loring Holding Company, Grindeland said, were now “reduced to a literal diet of bread and water.” No Cochran enterprise should ever be approved, he warned. Commissioner Nelson approved Hardstone Little Falls just the same.

But other commissioners smelled a rat. Nelson immediately went on a long vacation. He had, after all, been in office a year. Four weeks later, on August 24, the insurance and banking commissioners ordered suspension of all trading in Hardstone stocks until the companies provided more financial information. They never did. In October, they denied registration for Hardstone Appleton (with Nelson, wisely, not voting.) In January 1927, the commission ordered an investigation into Hardstone Duluth and Little Falls.

It’s one thing for an obscure commission to issue an order; compliance is something different. By the end of 1926, Cochran’s men had brought in nearly $2 million from the sales of notes, bonds, and stocks in Volkszeitung, Loring, the Hardstone Companies, and another Cochran entity—First Investment Company—overwhelmingly from people with German surnames. None of the companies made money.

Most made nothing at all.

Cochran and Lorenz had found an angle. World War I xenophobia, more virulent in Minnesota than elsewhere, had denigrated German culture and put German Americans on the defensive. The two and their salesmen played on the lingering resentment, hurt, and pride felt by many German immigrants to the Upper Midwest. In the state Securities Commission’s investigation file on Loring Holding Company, there is a small stack of typewritten notes that appear to be talking points for Cochran’s salesforce. One of them reads:

Are You German? Than [sic] invest your money in German-American Undertakings, not in British corporation [sic] who with your money pay the propaganda of those who call you Huns and Barbars. . . .

Some salesmen, it was said, asked Die Volkszeitung subscribers if they owned Liberty bonds. If the answer was yes, they were trained to reply, “What kind of German are you? That’s blood money!” Then, people would be urged to exchange the bonds for Volkszeitung securities. Agents hawking Loring Holding Company securities told investors that the hospital employed German doctors, German nurses, and German methods. Investors in Hardstone Brick stocks were told that the company used German machinery and German recipes. They most definitely had an angle.

The Unraveling

The unraveling began in January 1927. On January 15, Commissioner Nelson rescinded registration of Hardstone of Little Falls. But, for Nelson, it was too late. Gov. Christianson had already decided not to reappoint him because of complaints about the Cochran enterprises and let Nelson’s term expire at month’s end. On January 16, the Pioneer Press reported—front page—a lawsuit against the Volkszeitung Publishing Company by unhappy investors. Later in the winter, the state senate had directed the Ramsey County attorney to investigate dealings between Cochran and Nelson. In April, the Senate Rules Committee reported that it had found “irregularities” in Nelson’s dealings with Cochran and urged Ramsey County to investigate. When, on May 13, 1927, Ramsey County Judge R. D. O’Brien ordered seizure of Volkszeitung’s financial records, both Cochran and Lorenz had disappeared. On September 24, a federal grand jury in St. Paul indicted Cochran, Lorenz, Nelson, and nineteen others on federal mail fraud charges. Cochran was found in Chicago; Lorenz and three others remained at large.

A word here about the difference between state and federal courts. There are two parallel American court systems. Every state has its own courts, and that is where the majority of crimes are prosecuted. The US Congress created the federal courts in 1789 but gave them limited scope. On the criminal side, they may handle only offenses against federal law, such as federal tax violations and crimes that crossed state lines like wire and mail fraud. By the mid-1920s, federal agents and prosecutors knew how to use these laws—in this case, against mail fraud—to great effect. And, as Minnesota Attorney General Gustav Youngquist later explained, the federal mail fraud statute was much better in this instance than Minnesota’s tepid securities law—much harsher penalties and a better fit. Cochran’s essential crime was not the selling of securities but, rather, that the securities were worthless, that is, fraudulent. Any use of the mail in the scam—inevitable—brought the mail fraud law into play.

When trial began on January 16, 1928, in the St. Paul Federal Courts Building (now the Landmark Center), the defendants found Judge John B. Sanborn, Jr. presiding. They could not have been happy about that. Sanborn had been state insurance commissioner when Minnesota’s first securities laws were passed, which made him a member of the Securities Commission. Cochran, Ritter, and company faced a judge who knew the territory. What’s more, he knew Cochran and Ritter. They had appeared before him on check fraud charges in 1923 when Sanborn was a Ramsey County district court judge.

Sanborn, for his part, encountered an extraordinary scene: eighteen defendants (four others were on the lam, and one had pled guilty), two prosecutors, thirteen defense attorneys (Cochran conducted his own defense), twelve jurors probably not pleased to be sequestered in a nearby hotel, and a packed house every day in a smallish courtroom. Stamina would be tested and patience required. The trial went on for fifty days, including several evenings and Saturdays, the longest trial to date in the Minnesota federal court. The proceedings made the front pages almost every day.

The prosecutors—US Attorney Lafayette French, Jr. and his assistant, William Anderson—faced a host of challenges, not least of which was keeping the jury interested and engaged. Whole days at the beginning were taken up with wrangling about business documents and then reading them into the record—mind-numbing stuff.

But there were also compelling characters (including Cochran himself), moments of drama, and tales of pathos and betrayal. The prosecutors, who had the power to set the tone, went for pathos early. Starting January 31 after all the record-wrangling had been worked out, they brought on a host of aggrieved investors with life stories to tell.

Gustav Massow, age seventy, had sailed twenty-two years in the Kaiser’s navy then settled down and worked as a janitor in the courthouse at Redwood Falls. His life savings of $6,000 had gone into Volkszeitung. “Now I have only my home, no money, and my wife is sick.” He had met cannibals in the Papuan Islands, he said, but unlike Cochran’s salesmen, Louis Tobias and Alfred Meyer, “. . . they were kind and didn’t take anything from me when I was in need.”

Hugo Geese of Waseca limped to the witness stand. When he received $5,000 in compensation for losing a leg in a railroad accident, Cochran salesmen appeared and signed personal guarantees “insuring” his investment for the full amount in gold notes and bonds. Now the money, like his leg, was gone forever.

Carl Peters, a seventy-year-old farmer from Janesville, told of being persuaded to trade $2,400 in Northern States Power stock—worthless, he was told—for Volkszeitung securities. “They hypnotized me and I turned over Liberty bonds, too.” On and on it went—effective courtroom pathos.

Testimony at the trial revealed still more about Cochran and Lorenz’s methods. German-language circulars for the Volkszeitung Publishing Company promised:

You and your wife may depend on it that we will not recommend an investment to you through which our German readers would lose their money. Every one of our readers is in a similar position. . . , having saved a few thousand dollars through a lifetime of hard work and we do not wish to burden our German conscience and be responsible for the loss of the few cents they have saved up for their old age.

The cynicism is breathtaking. Separating their German readers from their life savings was exactly what Cochran and company so energetically set out to do.

Other circulars celebrated “the German spirit of invention [that] brings to shame all calumny directed against the Germans during the days of the war. . . . The American architects are very much enthused over the German hard brick and are ordering it [Hardstone] by the millions. . . .” If they were, they weren’t getting it from Cochran—he had no factories at all.

When Volkszeitung IOUs came due, the salesmen often appeared with Loring and then Hardstone stock certificates to exchange for the notes instead of paying with money. In private, Cochran told his team, “Use a lot of sob stuff. The more sob stuff you use, the quicker you will bring out their money,” and “Get some money. I don’t care how you get it, but get it. We will take care of the squawk.”

While the investors were paid—if they got anything—mostly with promises and stock, Cochran and his associates had been paid. At trial, a forensic accountant calculated that from October 1923 through March 1927, forty-one months, Cochran received $158,000. His top six salesmen earned $17,215 on average or about $100 a week. To put that in some context, a union newspaper pressman could expect to make about $45 a week. The accountant also found that on May 1, 1927, two weeks before its books were seized, Volkszeitung had $60.38 cash on hand. Cochran had taken a St. Paul institution, turned it into a criminal enterprise, and bled it dry. Now it had gone into receivership.

And it’s no wonder. Under the terms Cochran devised, for every $1,000 in one-year debt that Volkszeitung agents sold, Cochran got $50, the salesman $100, and the investor $70. Put another way, for every $1,000 Volkszeitung borrowed, it received $780. That’s an expensive way to do business. Cochran was looting his own company.

A Dirty State Player

The most spectacular revelations of the trial had to do with former securities commissioner Nelson. Why had he approved sales of the Hardstone companies securities despite Cochran’s unsavory reputation? The story came out at trial in a moment of some drama when the prosecution produced part of a letter that Cochran had written to Lorenz in February 1926:

I got word from a friend of mine that our Scandinavian friend on the Security commission [Nelson, presumably] was ready to enter into negotiations . . . He is not interested in stock, but is interested in cash, and a permit for [Hardstone] Duluth carries a modest fee of $50,000. . . .This outlandish price, of course, is a holdup . . .

Even for Cochran, just giving Nelson $50,000 was too direct. There was (at least according to prosecutors) a better way. While Nelson was a banker, he also had a side business: he and his family owned Stats Tidning, a Swedish-language newspaper that just happened to be located in the Volkszeitung building and printed on Volkszeitung presses. The business limped along.

What happened next was hotly disputed at trial, except for this: Nelson agreed to sell Stats Tidning to Cochran for $50,000. The deal was struck in February and the $15,000 down payment made soon after. Cochran got immediate access to Stats Tidning’s subscriber list, later called “the Swede sucker list,” supplementing the Volkszeitung’s “German sucker list.” Then, in April, Nelson approved the stock registration of Hardstone Duluth, and, in July, against the protests of staff, Nelson approved Hardstone Little Falls. At trial, Nelson swore that his dealings with Cochran had nothing to do with it, but the bald facts are these: when he approved the Hardstone registrations, Cochran owed him $35,000, which Nelson disclosed to no one. Thus, Nelson had a personal financial stake in the prosperity (and cash flow) of Clarence Cochran.

One more detail, in the category of “you can’t make this stuff up,” came out at trial. At the same time, in April 1926, Cochran bought $1,375 in diamonds from Nelson. Nelson saw nothing fishy about that either, or so he said.

The Verdict

The trial dragged on through February and into the middle of March. Cochran—thirty-eight years old, slim, bespectacled, a family man—testified that he took personal responsibility, sort of, for investors’ losses but put the blame for the collapse of his ventures, and thus the worthlessness of the securities, on the State of Minnesota. If only he had been allowed to keep going, to carry out the grand plan, the brick companies would have gotten their machinery, made their bricks, reaped their profits, and all investors would have been paid. But the meddling state stepped in just before it all came together. This is the classic defense of the con man and Ponzi artist.

The long-suffering jurors got the case on March 13, 1928, after fifty days of testimony. They took another fifty-one hours to reach their verdicts. Despite everything, they had been paying attention. They acquitted six lower-level salesmen but convicted Cochran and Nelson on all counts and the rest of the salesmen on most. Then Sanborn brought down the hammer: twenty years in Leavenworth for Cochran, Nelson, and Ritter. The five top salesmen were sentenced to ten years each. Of course, this did nothing for the victims. The Volkszeitung bondholders got back twenty cents on the dollar; everybody else got nothing.

Coda(s)

The case has a coda—or a series of them. Arthur Lorenz, on the lam, was caught in Toronto in March 1928 and duly tried, convicted, and sentenced to the same twenty years as Cochran and Nelson.

On March 28, 1929, State Rep. John A. Weeks, Minneapolis, introduced a bill in the legislature to indemnify those who had lost in the Volkszeitung swindle. The state, he said, had “a moral obligation” to reimburse because of Andrew Nelson’s central role in the fraud.

It was only then that the true scope of the con became public: Weeks published a complete list of those who had been duped and the losses of each. Cochran’s salesmen had found victims in sixty-three of Minnesota’s eighty-seven counties, plus many more in Iowa, Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, and Montana—over a thousand people in all. There were nearly two hundred victims in Ramsey County alone, their losses ranging from $20 to the gut-wrench suffered by German immigrant, William Schimmel. Married, with three children, renting a house in Frogtown, he had saved $14,000 (by one calculation nearly $250,000 in 2024) that he turned over to Cochran. He lost it all, and there was irony to boot: Cochran’s agents were trained to denigrate Northern States Power stock as worthless trash compared to good German enterprises like Hardstone Brick and get customers to trade it for Hardstone stock. Schimmel labored underground every day for Northern States Power.

The numbers testify to the extraordinary energy and effectiveness of Cochran’s agents. Unlike, say, financier Bernie Madoff, who fleeced mostly the rich, Cochran and company went after those who could afford to lose nothing. And unlike Madoff’s clients, who reaped bountiful returns until it all came down, Cochran’s investors were promised, at most, a 7 percent return. This was such a Minnesota con: the investors were promised no risk, yes, but only modest returns, and not in, say, precious metals hedge funds, but in bricks. Weeks’s bill, which caused a great hubbub in the House, possibly because it was designed, in part, to embarrass Gov. Christianson, was voted down decisively a few days later.

Nelson, Cochran, and their cohorts appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and lost. Nelson and Cochran reported to Leavenworth in 1930; Lorenz in 1931. But Nelson didn’t stay long. The shame, ordeal, and expense of the case, according to one press account, broke his health. He was sixty-two years old but looked older. After two years in Leavenworth, Pres. Herbert Hoover gave him a pardon on August 18. He was released six days later. Nelson returned to Minneapolis and died there in March 1933, at age sixty-five.

Clara Bergmeier was never accused of a crime, but testimony showed that on at least two occasions she assured nervous investors that her company (by then, no longer hers) was sound. The receiver for Volkszeitung sued her for $174,000; what became of that lawsuit is unknown. She died in St. Paul in 1934.

Arthur Lorenz entered Leavenworth federal prison on November 21, 1931. In April 1935, he was transferred to a federal medical center in Springfield, Missouri. What became of him after that is also unknown.

Clarence Cochran received a commutation of his twenty-year sentence and was released on December 22, 1936. For orchestrating the theft of $2 million and destroying the life savings of over a thousand people, he served slightly more than six years in prison. Cochran moved to Milwaukee, then back to St. Paul, where he died, living on Ashland Avenue, in 1963.

Lessons Learned

Was anything learned from the exposure and prosecution of the Volkszeitung fraud? The victims probably had a light go on—but too late. Nelson might have recognized that a public official should not sell diamonds to someone he is supposed to be regulating—again, too late.

But it’s probably safe to say that the people of Ramsey County and the rest of Minnesota learned nothing. The exposure of financial frauds was and continues to be followed by more and even greater frauds. The human desire for wealth without risk and the capacity for self-delusion make an irrepressible pair. Cochran’s was Minnesota’s fraud of the century—but not for long.

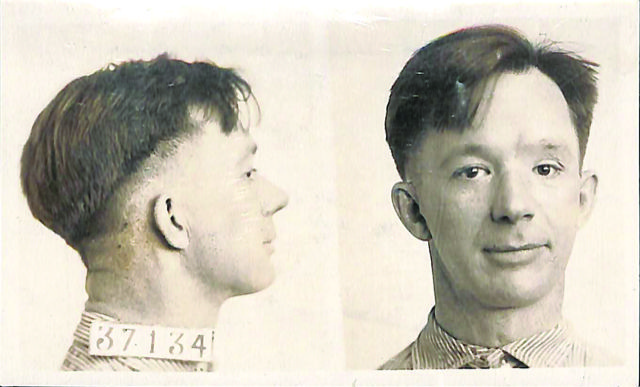

Acknowledgments: The author is grateful for the timely and creative assistance of Stephen Spence of the National Archives and Records Administration in Kansas City, especially for the prison mugshots of Andrew Nelson and Clarence Cochran.

Paul Nelson is an amateur historian living in St. Paul. Born and raised in Ohio’s Connecticut Western Reserve, he is the author of many publications of Minnesota history and a graduate of the University of Minnesota Law School. He is a frequent contributor to Ramsey County History magazine.

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2024

- Creators

- Paul Nelson

- Topics