Communist Clarence Hathaway and His Powerful Impact on Minnesota Politics

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 4, Fall 2024

- Creators

- Jim McCartney

- Topics

By Jim McCartney

Communist Clarence Hathaway liked what he saw as he looked over the crowd that packed the St. Paul Auditorium at the 1937 Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party Convention. Among the 300+ delegates, he estimated that eighty to eighty-five were Communists. Hathaway and Minnesota Communists enjoyed what few radical ideologies ever before attained: an intimate relationship with a major political party and the executive branch that controlled it. The key was the connections Hathaway had forged with the administrations of Gov. Floyd B. Olson (1931-1936) and Gov. Elmer Benson (1937-1939), including personal relationships with those two leaders.

The communist influence also came from its participation in the Farmer-Labor Association clubs that made up the party’s grassroots. And Communists were present in Minnesota’s unions, as well. In fact, the Communists played a substantial role in the party until they were ultimately expelled from the new four-year-old Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party in 1948 as hysteria about perceived communist threats against the United States began to intensify.

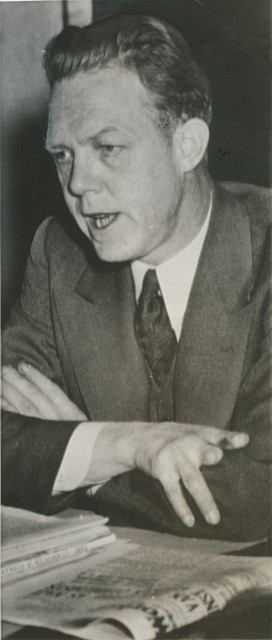

Few Communists played a bigger part in influencing Minnesota politics and government than Hathaway, who at the height of the US Communist Party’s power and popularity in the 1930s, was considered one of its “Big Three” leaders, alongside Earl Browder and William Z. Foster.

A Life of Personal and Professional Turmoil

Clarence A. Hathaway was born January 9, 1894, in Oakdale Township, just east of St. Paul and attended high school in Hastings. He became a tool and die maker and joined the International Association of Machinists (IAM) in 1913 at the age of nineteen. Lean, blonde, and athletic, Hathaway looked like an “All-American boy”—some say he even played semiprofessional baseball.

Despite his lack of postsecondary education, Hathaway would become a powerful speaker, writer and editor, and an influential political activist and labor organizer. This was at a time when Minnesota workers and farmers assembled and organized to confront the power of railroads, banks, and corporations, challenging them directly but also wielding significant power over local and state governments. As a worker who grew up in a rural area, Hathaway understood the concerns of farmers and workers, and he became a powerful advocate and speaker for them.

Orville Olson, a Socialist who worked in Gov. Benson’s state highway department, said Hathaway was one of the greatest speakers he had ever heard, noting a time he saw the leader address a crowd in New York City:

. . . I’ll never forget it. . . . the place was packed, he’d talk in a whisper and people could hear him all over. . . . He had that capacity for bringing points home.

Hathaway also had a personality that one historian described as “gay, warm, and slightly unstable.” His penchant for liquor, women, and errant behavior would lead to both personal and professional turmoil throughout his life.

Three Fingers: “The Sign of His Trade”

Despite his accomplishments in other areas, Hathaway was especially proud to be a machinist. Testifying in court years after he left the factories, Hathaway held up his right hand, showing the stumps of his index and middle fingers. “That is the sign of my trade,” he said.

While a machinist, Hathaway quickly rose in the ranks of the Minnesota labor and political movement. In 1922, he was elected IAM’s business agent for the Minnesota district and parts of Wisconsin, representing member interests and speaking on their behalf to management and the public while also handling negotiations and grievances. The following year, he became a vice president of the Minnesota State Federation of Labor, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which represented skilled workers.

He got involved in local politics, too. In the early 1920s, he became secretary of the Working People’s Nonpartisan Political League (WPNPL), which had been established, in part, by William Mahoney, a St. Paul union organizer who would one day become the city’s mayor. The WPNPL was the urban equivalent of the Nonpartisan League, which had been formed earlier in the 1910s by Minnesota farmers frustrated by price-gouging middlemen at grain elevators, railroads, stockyards, and banks. Hathaway worked with Mahoney to merge the two groups into the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Federation, personally introducing the merger proposal at a joint convention in St. Cloud.

The quick rise and stunning success of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party—representing both farmer and worker organizations—prompted Hathaway to help Mahoney try to establish a national Farmer-Labor Party with Progressive lion Robert La Follette at the head of its ticket. The two Minnesotans organized a national convention in St. Paul in 1924.

At the time, it was not well-known that Hathaway was a Communist. In 1915, in the midst of World War I, he moved to Scotland, working in a shipyard in Glasgow, then in Dundee, and, finally, at a metal factory in Manchester, England. All were hotbeds of labor unrest. In 1916, Hathaway returned to Minnesota a Socialist.

On August 30, 1919, he traveled to Chicago as a delegate to the Socialists Emergency National Convention. But a rift between the “Regulars” and the “Left Wingers,” who were energized by the Communist Revolution in Russia, led to left wingers (including Hathaway) to be refused seats at the convention. As a result, the left broke away that same weekend to organize the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

In the early 1920s, Hathaway was head of Minnesota’s Communist Party and established a communist presence in the IAM. In 1923, he joined CPUSA’s National Committee.

His efforts to build a national Farmer-Labor Party were made with the support and encouragement of the Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky in 1924. Hathaway served as secretary for the Farmer-Labor Party’s first national convention in St. Paul, which convened June 17 of that year, as mentioned above.

The disclosure of communist involvement in the convention led La Follette to denounce the gathering and withdraw less than a month before it opened. Meanwhile, a power struggle following Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin’s death in early ’24 led to a shift in Moscow’s thinking: rather than merely support a new third party, they wanted more control. While many Progressive delegates stayed home after La Follette’s withdrawal, the Communists attended the Farmer-Labor convention in force. They would take it over, adopt a revolutionary platform, and substitute their own slate of candidates at the top of the ticket. Mahoney did not see this coming.

And Hathaway was likely surprised by Moscow’s pivot in approach to the convention, as well. He was ordered to assign Communist delegates to influence other delegates. When the treachery became too much. Hathaway fled the convention, allegedly ending up in a “speakeasy where he had drowned his troubles and eased his conscience with bootleg liquor.”

Later, in the Daily Worker, the widely circulated newspaper of the CPUSA, Hathaway wrote that by taking over the convention, the Communists ended up with “a house of cards that crashed on our heads.” The fiasco soon led to the expulsion of Communists from the Farmer-Labor group and from the local labor movement. They wouldn’t return to the Farmer-Labor Party for a decade—a return led by Hathaway.

Hathaway’s Rise in the Communist Party

Hathaway survived the heated factional battles in the CPUSA during the mid-1920s through his deft ability to shift allegiances. The ouster from the Farmer-Labor Party didn’t discourage Hathaway from speaking to audiences about CPUSA. For example, in March 1925, as Minnesota’s district organizer, he gave four talks in Duluth on “The Growth of a Communist Party in the United States,” “The Decline of Capitalism,” “The American Labor Movement Today,” and “Farmer-Laborism in Minnesota.”

In 1926, on the recommendation of his American Communist mentor, James Cannon, Hathaway was sent to Moscow to join the first class of the new, prestigious International Lenin School (ILS) for party activists. School instructors, whose goal was to develop a core of disciplined Communist cadres worldwide, taught academic courses and practical political techniques.

However, in Russia, Hathaway showed signs of personal turmoil that would later upend his life. After a drunken fight with a Moscow policeman, he received a strict reprimand from the party. He split from his wife, Florence, who had stayed behind in the US with their children. He would eventually remarry a fellow Communist from Lithuania (then part of the Soviet Union). A biographer of Hathaway concluded: “Heavy drinking during his stint in Moscow and desertion of his wife and three children did his reputation little good.”

While in Moscow, Hathaway saw Cannon swayed by the ideas of Trotsky, who had become disenchanted with the post-Lenin leadership and was expelled from the party in 1928. Back in America, Hathaway broke with Cannon and spearheaded a drive against Trotskyism, which ultimately led to Cannon’s expulsion from the party that same year.

Hathaway soon allied himself with Earl Browder, who was taking over the CPUSA. Under Browder, Hathaway assumed a rapid succession of important party jobs, first as a district organizer in New York, and then as editor of the monthly magazine of the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), Labor Unity.

In the early 1930s, mostly from New York, Hathaway managed William Z. Foster’s campaign for US president and ran his own campaigns in 1930, 1932, and 1934 to represent New York in Congress.

If that wasn’t enough, in July 1933, he became editor of the New York-based Daily Worker. That year, there were hundreds of articles about Minnesota in the national paper, primarily focusing on the state relief march to the Minnesota legislature by members of a dozen local unions, along with continuous meetings about joblessness. The Hormel Meatpackers’ Strike in Austin, Minnesota, which began early in the year, sparked strikes or threats to strike at other packing plants, including the Armour and Swift & Co. facilities in South St. Paul (Dakota County). The Daily Worker kept readers informed of the fights for rights by local members of the Packinghouse Workers Industrial Union. And the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike, in which deputized private police and strikers died in separate incidents, headlined the front pages of the Communist paper over the summer of 1934.

Depression/Fascism Reunite Communists/Farmer-Labor

During the Great Depression, the Soviet Union began to be viewed by many Americans in a new, more positive light. The “workers’ state” with its planned economy seemed to offer frustrated farmers and workers a desirable alternative to the failed capitalist system, with its mass unemployment and widespread social misery. In addition, as the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, Soviet leaders shifted their international strategy from promoting world revolution to seeking antifascist alliances with Western democratic powers, endorsing the idea of a coalition or popular front of communist and noncommunist forces.

Moscow’s suggestion that the American Communists form a nonrevolutionary left-wing party led them to Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor Party, which they envisioned as a cornerstone for a nationwide Farmer-Labor movement. To guide the local Communists’ reentry into the Farmer-Labor Association, CPUSA sent two national officers to Minnesota: Browder and Hathaway.

Hathaway “returned to his old haunts, conferred with [Minnesota’s governor, Floyd] Olson, and guided the Party caucus.” The local Union Advocate noted that Hathaway visited Minnesota repeatedly in 1936 to convince fellow Communists to show some “brotherly love” to the Farmer-Laborites.

The Communists’ bitter attacks on Olson and his programs ceased. They conceded that “serious mistakes were made in the past” in relation to the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party and now hailed the party as an answer to the failures of the New Deal. Hathaway went on the radio in 1936. “My friends,” he said, “let us build a peoples’ front, a Farmer-Labor Party.”

Meanwhile, Olson and the left wing of the Farmer-Labor Association quietly welcomed the Communists back into Minnesota politics. As noted previously, Communists had been banned from membership in the Farmer-Labor Party since 1925—the result of the 1924 national Farmer-Labor Party convention debacle.

Olson made it easier for Communists to join the party, and at the party’s 1936 state convention, about forty of 667 delegates, or 6 percent, were Communists, according to estimates from Minnesota Communist Nat Ross. That would grow exponentially over the year so that, at the 1937 convention, the percentage of Communist delegates exceeded 25 percent (eighty to eighty-five Communists out of 300 delegates), according to Hathaway’s estimates.

In February 1936, Hathaway bragged to Browder of the “many very favorable developments” in Minnesota. “We have ready access to the leading circles of the Farmer-Labor Party and, to a considerable degree, of the trade unions.” Meeting secretly with Olson and Benson, the two had “the specific task of organizing the left-wing.” At the 1936 Farmer-Labor convention, Communists participated in all activities of the convention, including the leading committees, Hathaway reported.

Although 1936 was a strong election year for the Farmer-Labor Party, it was also the year it unexpectedly lost its leader and most popular figure, Floyd Olson.

While often mentioned as a candidate for US President, Olson had announced in November 1935 that he would run for the US Senate. A month later, two events rocked that Senate race: Olson’s opponent, longtime incumbent, Republican Thomas Schall, died in a car accident; and Olson discovered he had stomach cancer.

Olson appointed Elmer Benson, his state banking commissioner, to succeed Schall. Benson, for his part, announced that he would run for governor. When Olson died in August 1936, several weeks before the election, he was succeeded by his lieutenant governor, Hjalmar Peterson, who led the state for all of four months.

Ultimately, Benson won the governor’s race. Olson’s replacement on the Farmer-Labor ticket—Ernest Lundeen—won the US Senate race, and Farmer-Laborites secured five of Minnesota’s nine congressional seats. It was an impressive showing by the Farmer-Labor Party, despite Olson’s untimely death.

To Browder, Minnesota was a model for how to successfully execute the popular front strategy.

A Fraught Relationship

Of course, there were wrinkles in the new partnership. Early on, Hathaway fretted that Gov. Olson had become too chummy with the Democratic Party in agreeing to become part of the New Deal coalition. He also groused that Minnesota Communists were too friendly with the Farmer-Laborites, not only because of Gov. Olson’s alliance with the Democratic Party, but also because of his uncritical support of the New Deal, and his antiunion role in the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike. Browder eventually asked Hathaway to temper his criticism.

Although Communists were allowed into the Farmer-Labor Party, this relationship was kept quiet because many voters found Communism objectionable, stemming from the initial Russian revolution (1917-1923) and the creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). But this secrecy bothered Samuel Darcy, another national Communist figure, who complained about the “furtive goings and comings through side doors.” He noted that some Farmer-Laborites felt that the secretive communist forces manipulated or menaced them.

Darcy argued that a more open relationship would help Benson and the Farmer-Labor Party counter a growing swell of anti-communist criticism both from outside and inside the party. Browder disagreed, viewed Darcy’s criticism as an attack on his popular front policy, and had him demoted.

Seeds of Self-Destruction

Eventually, this quiet alliance and the growing opposition to it led to troubles for both Farmer-Laborites and the Communists. When Gov. Benson’s legislative platform flagged after the 1936 elections, Hathaway suggested that a “people’s lobby” push reform legislation. With the blessing of Benson and his party, 2,500 people gathered in St. Paul on April 4, 1937. The next day, they marched to the state capitol and pushed their way into the building. Some 200 demonstrators—many Communists—settled in the senate chamber overnight. Early the next morning, Benson stopped by to tell them they had “done a good job” and then requested they leave.

The unease and anger over the “people’s lobby” fed the growing hostility within the Farmer-Labor Association toward both Communists and Benson.

Meanwhile, a newly elected Farmer-Labor congressman in Minnesota brought unwanted attention to his communist ties. In 1936, Hathaway, with the aid of the Communist Finnish Workers Clubs in northern Minnesota, had helped John Bernard win a congressional race to represent Minnesota’s eighth district. Bernard was the only member of Congress to vote against imposing an arms embargo on Spain after the Spanish Civil War broke out between the left-leaning popular front and the right-leaning nationalists. He also read stories from the Daily Worker into the Congressional Record on a daily basis. Bernard’s communist sympathies made some members of congress uneasy.

The stories about communist influence in the Farmer-Labor Party brought Minnesota to the attention of the Dies Committee (House Committee on Un-American Activities), which would later work with a similar US Senate committee headed by Sen. Joseph McCarthy. The growth of anti-communist sentiment in America, reflected in these two committees, would peak during the Cold War, during which anyone suspected to be associated with the Communist Party was treated, often unfairly, as a pariah.

Farmer-Labor Party Stress

By this time, the Minnesota popular front model showed weakness. Gov. Benson was in trouble with both the legislature and the state’s unions, and he faced an ugly primary challenge from Hjalmar Petersen, who wanted to win back the governorship. At the same time, Hathaway warned the Communist Political Bureau that the Republican Party—particularly its gubernatorial candidate, Harold Stassen—was becoming a threat to the Farmer-Labor Party.

Although anti-communist sentiment was strong at the 1938 convention, the left wing still had enough sway within the Farmer-Labor Party that Hathaway blocked a concerted anti-communist movement within the party. Still, in a speech at the University of Minnesota in October that year, Hathaway felt compelled to minimize the communist influence:

All this talk about the sympathy Governor Olson, Governor Benson and other Farmer-Labor leaders have had for communism is just so much hooey. . . . As for the claim Moscow is singling out Minnesota for special attention and dictating our work here—that is sheer fantasy.

Ultimately, Benson won the nomination but, as Hathaway predicted, was easily beaten by Republican Stassen in the general governor’s race. Most Farmer-Labor congressmen, including Bernard, lost that year. In 1939, the Farmer-Labor convention stiffened the prohibition against Communist membership and expelled fourteen known Communist delegates (out of sixty-three). Because anti-communist sentiments were strong enough in the US that few people publicly acknowledged they were Communists, it was difficult to prove a delegate was Communist.

Darker days for Hathaway would soon follow. A series of personal and professional missteps, combined with the growing pressure to defend the shifting positions of Bolshevik leader Joseph Stalin during World War II, would end up nearly destroying him.

Sued for Libel

In 1936, Hathaway, as editor of the Daily Worker, had come to the defense of Olson and the Farmer-Labor Party following the sensational murder of Walter Liggett, a muckraking editor from Minnesota. As a result, Hathaway quickly became embroiled in libel suits.

Three years earlier, Liggett had returned to Minnesota to help build the Farmer-Labor Party as editor of a new newspaper, the Midwest American. However, Liggett soon became disenchanted with Olson and wrote articles about corruption in Olson’s party, especially its alleged ties with organized crime leaders, such as Isadore Blumenfeld, aka Kid Cann. Liggett called for the FBI to investigate the situation as they had recently done with Al Capone in Chicago.

Despite bribes, threats, and even a beating from Kid Cann and his gang, Liggett refused to back off. On December 9, 1935, he was gunned down in the alley behind his Minneapolis apartment as his wife Edith and daughter Marda looked on. Kid Cann was charged with murder but acquitted. No one else was ever charged.

After Liggett’s death, his widow and others, including the Republican Party, continued investigating Olson and organized crime, implying that Olson was complicit in Liggett’s murder. After reading about the situation and conferring with union and Farmer-Labor Party officials, including Olson, Hathaway assigned, approved, and likely helped write a series of articles for the Daily Worker that attacked Liggett, his widow, Republicans, and other Olson critics.

A front-page Daily Worker story, “Liggett Was Murdered by the Underworld for His Scavenging,” called Liggett a “traitor to the Farmer-Labor Party, a blackmailer who demanded loans from underworld characters, and a cheap tool of the Republicans.” The coverage accused Edith of “trying to capitalize, politically and financially” on her husband’s death, adding that “it is especially disgusting to see the widow of the slain publisher selling the corpse limb by limb to the highest bidder of the Minnesota Republication party.”

In 1938, Edith sued the Daily Worker and Hathaway for libel in New York. The prosecuting attorney for the related criminal libel case was Thomas E. Dewey, the aspiring Republican district attorney of New York.

Hathaway testified that the stories were intended to look at how the Republican Party used Liggett’s murder to hurt the Farmer-Labor Party. Outside court, the Daily Worker claimed that the libel case was “spawned by the Trotskyists and utilized by [prosecutor Thomas] Dewey to further his Presidential ambitions.”

Hathaway lost in court; the judge said he was guilty of “outrageous, vile and cowardly libel. . . .” Out on bail on appeal, Hathaway was restricted from leaving Brooklyn for six months but continued his duties as editor of the Daily Worker and public representative of the CPUSA. In 1940, Hathaway served a brief jail term.

Explaining Stalin’s Shifting Stands

During the course of the trials, the Communist Party position in world affairs rapidly moved from espousing antifascism to pacifism after the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact (Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) was signed on August 23, 1939, and then to interventionism when Hitler invaded Russia on June 22, 1941.

That was a lot to explain to the American public for high-profile Communists like Hathaway. He was caught off guard when the pact was revealed, given that he recently denied rumors of the agreement by retorting that “there is as much chance of that as of Stassen and I getting together.”

Barely a week after the pact was signed, Germany invaded Poland. Great Britain, then France, declared war on Germany. Now, the Communists saw the war as a conflict between two “imperialist camps” and insisted that America should stay out of it. In a lecture on April 27, 1940, Hathaway said that America wants to keep the “war going” to profit from it by selling “planes, raw materials [and] cotton” to England and France.

The Hitler-Stalin Pact damaged the Communists’ alliance with New Deal liberals. Many popular front organizations collapsed when the Communists insisted that the groups support US neutrality in the war.

In 1939, The New Yorker’s “The Talk of the Town” column skewered Hathaway’s increasingly frenetic situation as a busy editor and apologizer for Stalin:

Certainly the most harried of Communists these days is the editor of the Daily Worker, Clarence Hathaway. Not only does he have to explain, over and over again just what he thinks Stalin is up to but he is legally confined within the boundaries of Kings County, and he has to do both editing and explaining by remote control.

The New Yorker sarcastically noted that Hathaway’s saving grace was that the Brooklyn Dodgers were doing well, and, during his confinement, Hathaway could attend baseball games at Ebbets Field. Hathaway’s troubles soon got worse.

Expelled

In October 1941, Hathaway was expelled from the Communist Party. The party blamed Hathaway’s “failure to meet personal and political responsibilities,” “desertion,” and refusal to “rehabilitate himself.”

The New York Times suspected the departure of Hathaway, one of the “Big Three” in the American Communist Party, was “the most spectacular defection in the series of expulsions and resignations that began with the signing of the Hitler-Stalin Pact.” He was regarded as one of the party’s “ablest speakers and writers,” the Times said.

Hathaway publicly accepted the punishment with little comment other than it was “justifiable” because he couldn’t live up to his leadership’s “exacting personal standards.”

Hathaway’s problem drinking was blamed for the expulsion—a habit perhaps exacerbated by the pressures of defending Stalin’s pact with Hitler and a bombing attempt on the Daily Worker offices. Some historians say the libel trial, including jail time, was also a factor in his expulsion; others point to his personal strife, such as leaving his wife and children and his reputation for “carousing with women.”

The Soviet archives reveal that Moscow knew of some other troubling incidents involving Hathaway. One was from 1912, when Hathaway joined the National Guard of Minnesota, which suppressed workers’ riots and protected strike breakers. Another was a claim by his former wife that he had been a police informer.

Reemerging in St. Paul

After his dismissal, Hathaway disappeared from view. The New York Times reported that he had vacated his Brooklyn apartment without leaving a forwarding address. Commonweal magazine suspected that Russian military espionage may have caused his disappearance.

Not until 1946 did the media “discover” Hathaway. He had returned to St. Paul around 1945, working as a machinist and shop steward. He quietly and successfully reapplied to the Communist Party and then emerged as a union leader at the Industrial Tool & Die Co. He lived at 106 N. Smith Avenue, St. Paul.

With his drinking under control, Hathaway began to reassert his influence on union affairs and local politics as a Communist Party ally. He became a successful organizer for the United Electrical and Machine Workers Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), helping them negotiate their initial contract, after which he was elected shop steward and a delegate to the Hennepin County CIO Council. In April 1946, he was appointed a business agent for the CIO United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers union, Local No. 1139, where he assisted in negotiating a 16 sixteen-cent pay hike for 125 striking workers of Telex, Inc.

That same year, Hathaway was named member of Minnesota CIO, part of a group that demanded fifty-two weeks of pay a year, slamming salary practices at George A. Hormel & Co. (Austin) and Superior Packing Co. (St. Paul). Later in the year, after a temporary injunction, Hathaway led picketers against Osseo’s Bishman Manufacturing plant, demanding a fifteen-cent-per-hour wage increase, paid holidays, and the reestablishment of a union shop.

Soon, he would play a significant role again in Minnesota politics.

“Rescuing” Hubert Humphrey’s Early Career

Weakened by its association with Communism, in 1944, the Farmer-Labor Party merged with the Democratic Party to form the Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) Party. Farmer-Labor founder William Mahoney, who had left the party over its association with Communists, warned the Democrats that they were being “badly duped” by agreeing to the merger due to his former party’s continued connection with Communists.

In a 1967 speech in Oklahoma, Minnesota’s Hubert Humphrey, who at the time was vice president under President Lyndon B. Johnson, explained that, in 1946, the DFL was “dominated” by a “group of 50 to 100 Communists,” naming Hathaway foremost among that group.

Ironically, Hathaway may have helped save Humphrey’s fledgling political career. During the 1946 convention, the Communists could have nearly destroyed Humphrey—then the young mayor of Minneapolis. Some labor officials were frustrated with Humphrey’s intervention in labor disputes, including with Bell Telephone, as well as not allowing labor leaders to help choose a new police chief. They were ready to vote with the Communists to minimize Humphrey’s role in the DFL Party.

During the subsequent discussion among convention leaders about whom to endorse, the sentiment was to back left wingers only. But Hathaway intervened and convinced the left, including Benson, that, for unity and “the good of the party,” they should back a mixed slate. As a result, Orville Freeman, one of Humphrey’s closest colleagues, became party secretary.

Benson later said that this move gave the moderate wing of the party—which he called the “termites”—the opportunity to take it over. And so they did. In 1948, Humphrey won a US Senate seat, and his career took off. A Humphrey campaign leaflet asked: “Will the D-F-L party of Minnesota be a clean, honest, decent, progressive party? Or will it be a Communist-front organization?” Soon, the Communists were permanently sidelined by the DFL.

Whether or not he knew about Hathaway’s quiet, inadvertent effort in salvaging his nascent political career, Humphrey was proud and public about his role in ousting Hathaway and his fellow Communists from the DFL. For example, during his speech in Oklahoma, Humphrey reflected, “I’m in national politics today because . . . Orville Freeman and myself and a few others out there had the courage to come to grips with Communist domination.”

Back Up the Communist Ladder

By 1948, the anti-left-wing had set in among labor circles, too. Paranoia about Communism within and outside of unions escalated. Slowly, the period known as the second “Red Scare” (McCarthyism) took hold of the nation. In 1948, Hathaway was one of several state leaders supporting presidential candidate Henry Wallace, who ran on the new Progressive Party ticket and served as the thirty-third vice president under Franklin D. Roosevelt. The CIO moved to oust the leaders for violating union rules related to the campaign. In December 1949, Hathaway was dismissed from his role as business agent of the local union.

Despite everything, Hathaway continued working in St. Paul, living at 1455 Fulham with his second wife, Vera. In 1953, Vera, was arrested by immigration for possible deportation back to the Soviet Union. The case languished in the courts for several years. Eventually, the couple moved to New York, where Hathaway made another remarkable comeback, rising to lead the Communists’ all-important New York district in the late 1950s. Then, he was considered for a powerful position on the party’s National Committee.

During the vetting process in February 1960, however, Moscow again raised objections to Hathaway. Besides the earlier concerns (drinking and womanizing), Moscow had new ones—including the bombshell that, after his expulsion, Hathaway had been in contact with FBI agents in 1941 in Pittsburgh and 1947 in San Francisco. In addition, Moscow revealed that Hathaway had been an FBI informant since 1920, initially spying on a national meeting of Communist leaders at the Overlook Mountain Hotel in Woodstock, New York, in May 1921.

American Communist leaders Eugene Dennis and Gus Hall were shocked. Further ugly details emerged about Hathaway, who had allegedly “absconded with some money and ran off to Arizona with some woman” in 1943.

Hall confronted Hathaway and his wife at their anniversary party in 1960, announcing to them and guests that he had heard Hathaway was an FBI agent. Apparently, the couple did not react. However, later that evening, it’s been said, Hathaway consumed his first alcoholic drink in sixteen years.

Dennis explained this information put the party in a “hell of a fix.” If they fired Hathaway, they might lose the New York district. Instead, Hathaway was quietly shunted out of power, ostensibly for reasons of health.

Hathaway Joins “Radical Row”

Clarence Hathaway, who had suffered from emphysema, died in Los Angeles on January 23, 1963, at age sixty-nine. He was buried in “Dissenters’ Graves,” also known as “Radical Row,” near the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument in Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. Others buried there include William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, and Emma Goldman.

In labor historian Hyman Berman’s July 7, 1987-interview with one-time Communist leader and Minnesota radicalism historian Carl Ross, Ross recalled last hearing from Hathaway in his “later years,” when Hathaway either “was going up the ladder or reached the bottom. I’m not sure which.”

Ross emphasized that Hathaway was “a guy with such talents and with such long historic labor and political contributions.” Berman agreed, calling Hathaway one of the “last of the Mohicans” of the American Communist Party.

Jim McCartney is a St. Paul author who wrote a cover profile of Farmer-Labor Party founder William Mahoney for the Fall 2022 issue of Ramsey County History. After a long career as a newspaper journalist, including twenty-five years as a business reporter for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, he joined Weber Shandwick public relations’ healthcare and science teams in 2006, where he worked before going on his own in 2020.

See the following companion pieces:

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 4, Fall 2024

- Creators

- Jim McCartney

- Topics