Confluence: A History of Fort Snelling

- Year

- 2021

- Creators

- Reviewer: Matthew W. Wright

- Topics

2022 Minnesota Book Award Winner

![]()

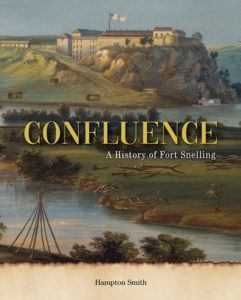

Confluence: A History of Fort Snelling

Hampton Smith

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2021

256 pages; hardcover; $34.95

The past six years have seen the publication of two new histories of Fort Snelling and its surroundings by the Minnesota Historical Society Press. These two books, Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History by Peter DeCarlo (2016; annotations added 2020) and Confluence: A History of Fort Snelling by Hampton Smith (2021), present the first book-length studies of the fort from (and before) its founding in 1819 to its final decommissioning after World War II.

Previous books, such as Marcus L. Hansen’s Old Fort Snelling: 1819-1858 (1918) and Evan Jones’s Citadel in the Wilderness: The Story of Fort Snelling and the Northwest Frontier (1966), focused on the early years of the fort until its first decommissioning in 1858, when Minnesota became a state. Other books have been published by Mary Henderson Eastman, Charlotte Ouisconsin Van Cleve, Henry Hunt Snelling, and, in recent years, Corrine L. Monjeau-Marz and Stephen E. Osman. However, these typically highlighted personal memories or particular aspects of the fort’s history and did not aim for comprehensiveness.

The DeCarlo and Smith books attempt to cover the entire chronological history of the fort. They will likely provide at least part of the foundation for the new interpretive plan for Fort Snelling, which, having recently marked its 200th anniversary, is in the midst of a major renovation and reorientation in its historiographical presentation.

Both books reflect, as earlier ones did, the preoccupations and prejudices of their era. Hansen, for example, wrote from a triumphal nationalist perspective and was primarily concerned with the fort’s role in establishing the sovereignty of the United States in a frontier territory after the War of 1812. The Smith and DeCarlo books are written largely from a postcolonial perspective that does not accept uncritically the legitimacy of US national expansion and privileges the perspectives of Indigenous people, particularly the Dakota. They also reflect present-day concerns with race, gender, and sexuality. This marks a clear shift in the way that the stories of the fort and its surroundings are told.

Smith’s book is divided into chronological chapters covering the fort’s history and its surroundings and their place in Dakota and Euro-American history before Zebulon Pike’s expedition in 1805 until the final chapter on the establishment and re-creation of Historic Fort Snelling as we know it today. Each chapter presents the history in the larger context of local, national, and world history, and is compellingly and accessibly written. Smith uses primary sources to great effect, including quotations from letters, journals, newspapers, maps, and paintings. The section on the place of dueling among officers at the fort under (and including) Colonel Josiah Snelling is particularly fascinating. There is also an attempt to include the stories of those seen as missing in previous histories, particularly Indigenous people, African Americans both enslaved and free, and women of all ethnicities.

The effort to include a fuller Native picture of the fort and its surroundings finds less success in Smith’s discussion of Dakota and Ojibwe warfare, which was a constant presence around the fort and in the territory until the forced removal of most of the Dakota in the wake of what is commonly known as the US Dakota War of 1862. As Theresa Schenck notes in her 2009 introduction to William W. Warren’s History of the Ojibway People (1885), “Warfare had . . . an eminent place in Ojibwe life in the first half of the 19th century . . . And not only had the Ojibwe-Dakota conflict extended over two hundred years of Ojibwe history, it was still going on, much to the horror of the newcomers to Minnesota Territory . . . it was indeed the most salient feature of aboriginal life at that time.” Smith does briefly note several instances of Dakota-Ojibwe violence in his book, but they are downplayed or couched in ways that emphasize cooperation and fellowship. This is a larger problem in DeCarlo’s book, which deemphasizes this conflict even more. These two books present an intentional shift in the historical representation of Minnesota’s Indigenous peoples that focuses less on the warrior cultures of the Dakota and Ojibwe and more on a story of Indigenous harmony, victimization, and survival.

Smith’s book successfully executes his goal of presenting a history of the fort and its surroundings that reflects the experiences of a variety of people. The question of the fundamental significance of the fort, which, in the view of Osman in Fort Snelling and the Civil War, was “how generations of soldiers and civilians used the fort as a fulcrum for regional growth,” is not disputed by Smith. However, his evaluation shifts from a positive or morally agnostic reflection of historical change to one of regret and critical reflection.

Osman also writes that “Indigenous peoples were displaced, as they themselves had displaced earlier native residents of the region.” This understanding of migration and conquest as a fundamental part of Indigenous (and, indeed, all human) history is missing in Smith’s book, which accepts uncritically the notion that the Dakota originated at the Bdote (confluence) of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers (discussions of other origin myths, such as at Lake Mille Lacs are also missing) and does not discuss archaeological and historical linguistic evidence of Dakota migration, which is admittedly inconclusive and contested.

The question of whether or not Euro-American colonization of the area surrounding the fort, and indeed, America and other modern settler colonies worldwide, is so qualitatively different from other forms of migration, displacement, and conquest as to necessitate this particular postcolonial historiographical perspective, I will leave for the reader to ponder.

Overall, Smith’s book is highly recommended for readers well-versed in the history of the fort and those new to the subject. The other books mentioned in this review also are necessary reading to understand the varied ways in which this important local historical site has been and can still be seen.

Matthew W. Wright studied history at St. Olaf College, Waseda University, the University of Washington, and UCLA. He has taught history and worked as a historical interpreter at the Minnesota State Capitol. He is a member of the Ramsey County Historical Society Editorial Board.

- Year

- 2021

- Creators

- Reviewer: Matthew W. Wright

- Topics