Fifty Years of Hmong Lives in Ramsey County

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2025

- Creators

- Chia Youyee Vang, PhD

- Topics

Reflections from the 1.5 Generation

By Chia Youyee Vang, PhD

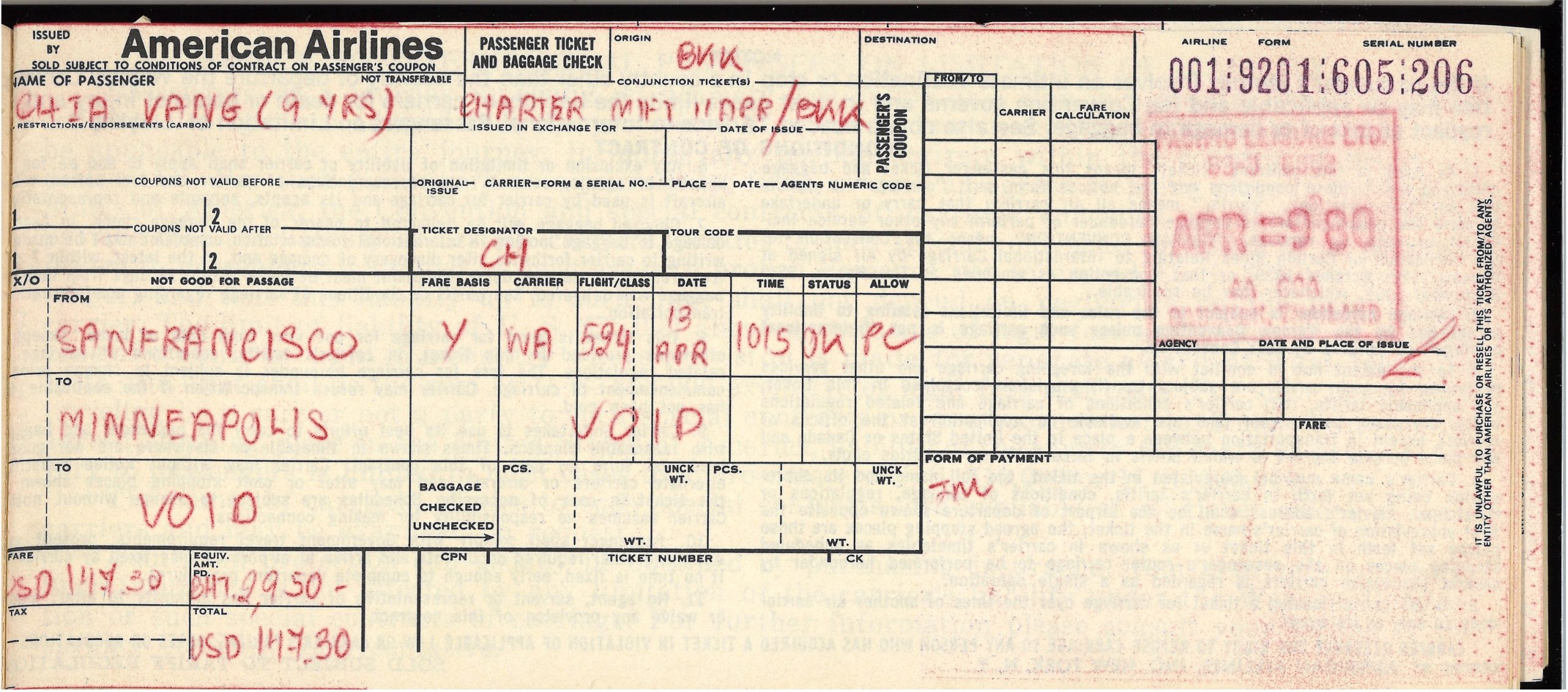

On April 11, 1980, my family of eight boarded an American Airlines charter flight at Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok, Thailand. The day before, my father, You Yee Vang, had signed a promissory note for a travel loan in the amount of $1,632. We arrived exhausted and disoriented in San Francisco. My father was 41 and my mother was 39. Years later, my parents shared that they were afraid throughout the international journey. Fear was accompanied by emptiness and a sense of helplessness because it was impossible to imagine what life would be like in America.

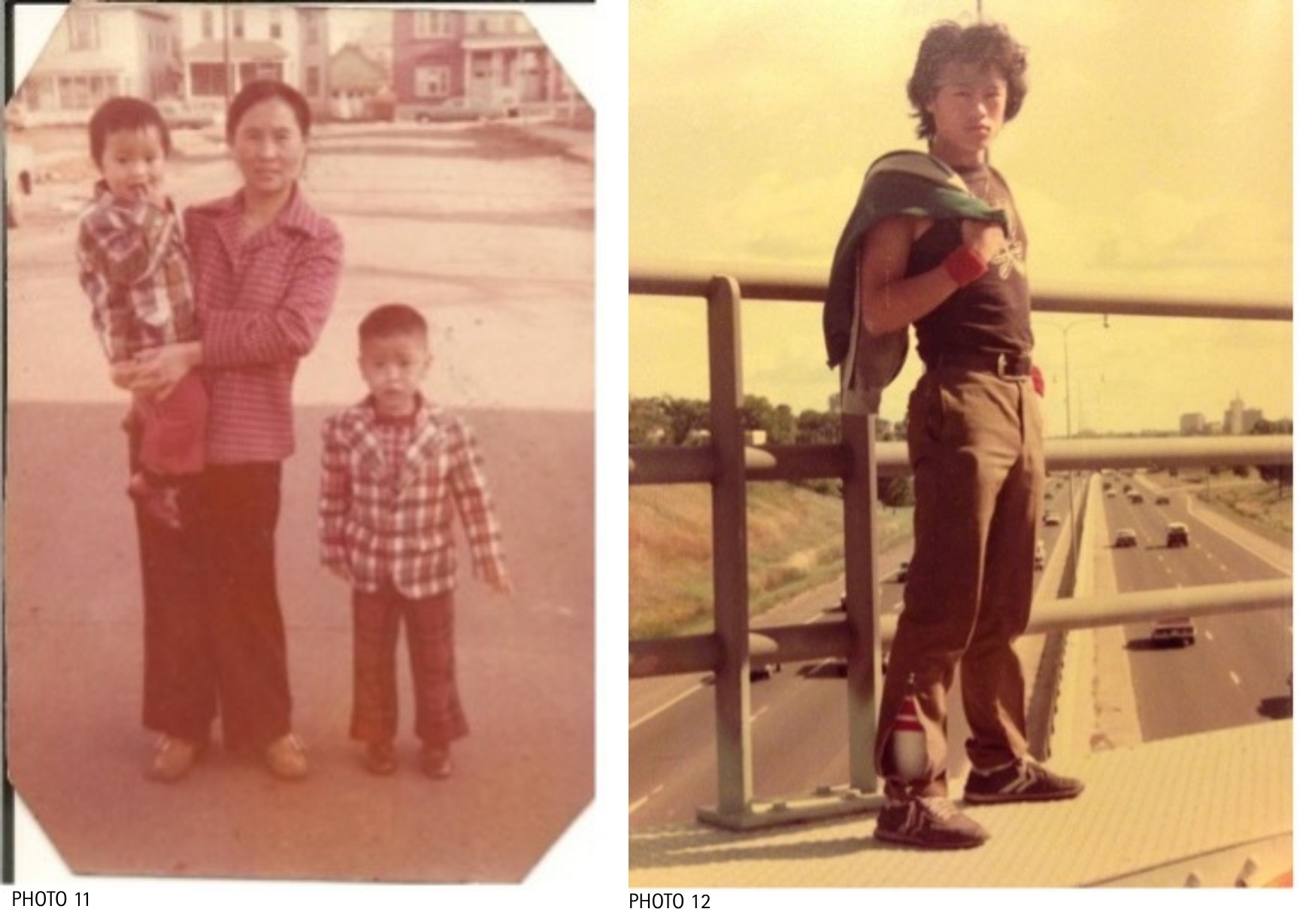

The six of us ranged in age from 2 to 14. We had spent the previous six months in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, before we were accepted for resettlement under the auspices of the American Council Nationalities Services. Our local sponsorship was the International Institute of Minnesota. We arrived with not much more than the clothes on our backs and were processed along with many other refugees. On the morning of April 13, we flew to Minnesota and were greeted by my father’s younger brother, Tong Vang, and his wife, May A Yang, at the Minneapolis-Saint Paul International airport. They had settled in Minnesota in 1976, just a year after the first Hmong refugees arrived in the state.

As a refugee child raised in St. Paul’s under-resourced neighborhoods, I had to overcome many barriers, including the insecurity caused by displacement on multiple levels; my family moved seven times before my high school graduation. Despite these challenges, I was able to go to college and eventually earn a doctoral degree, become a tenured professor, travel to many parts of the world, and now serve as vice chancellor at a large American university. While my personal experiences are mine alone, my story is certainly not unique. Out of the nearly 1.4 million people from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam who sought refuge in the United States following America’s disengagement from the Vietnam War, Hmong from Laos represented about ten percent.1 During the last few decades, the role Hmong played in the U.S. Secret War in Laos that occurred parallel to the larger war in Vietnam has been explored in films, books, as well as popular and academic articles.2

People of the diaspora have also been the subject of advocacy efforts to secure well-deserved recognition for both Hmong and American veterans who fought this secret war. About a dozen memorials have been erected to recognize their wartime contributions, including a small plaque on Grant Drive in Arlington National Cemetery and the Minnesota Memorial for the United States and Alliance Special Forces in Laos on the grounds of the Minnesota State Capitol. While there are more stories from this immigrant generation to be told, in locations where many Hmong Americans reside, there has been increased awareness among the general population about why ethnic minority people like them were forced to leave their way of life and escape to the United States. Much has been written about their struggles to integrate into American society.3 Parallel to these struggles were the tremendous sacrifices by the immigrant generation to survive at all costs, as well as an intense desire by us, their children who are the 1.5 generation, to overcome a range of barriers and realize the American Dream.

Although I have lived in the Milwaukee area for the last nineteen years, I consider St. Paul home. The physical location is where my immediate and extended family set down roots. It is the answer I give when people ask where I am from. It is also where I travel for most major holidays. In this article, I reflect on how Ramsey County became the county with the largest Hmong population in the United States, and what it was like growing up in St. Paul during the 1980s. In addition to my own reflections, I invited two of Ramsey County’s prominent Hmong leaders from my generation to share their memories. Collectively, our experiences demonstrate how our adherence to the Hmong values of hard work and commitment to family and community allowed us to create impactful personal and professional lives. In doing so, we and those from our generation were able to leave behind the margins to which we and our elders were initially relegated in order to build one of the strongest and most vibrant Hmong communities in this country.

Seeking Refuge

Following the April 30, 1975, fall of Saigon, some Hmong leaders in Laos who had worked with the Royal Lao Government and the American-sponsored clandestine secret army, along with their families, were airlifted to Thailand. Thousands found their own way out in the immediate aftermath. Over the course of the next two decades, many more escaped and sought temporary refuge in Thailand. Since 1975, about 145,000 Hmong were resettled in the United States as refugees. Where the new arrivals initially settled reflected the availability of state and local efforts to sponsor refugees, which resulted in people being dispersed across the country.4

The first Hmong family, Dang Her and Shoua Moua, arrived in Minnesota in December 1975. Dang was a parolee since he had served as a US Agency for International Development field assistant. More came the following year. Leng Wong (formerly Vang) and his family were the first Hmong refugees to be resettled in the state. As the situation in Southeast Asia further deteriorated, the number of arrivals continued to increase. From 1975 to 1980, more than 40,000 had been resettled throughout the country, but the 1980 Census counted only 5,208 people of Hmong ethnicity.5 In the subsequent decades, the U.S. Hmong population increased exponentially. The United Nations-sponsored refugee camps in Thailand closed in the mid-1990s. Thereafter, the growth of the population was attributed largely to natural increase.

Today, Ramsey County is the county with the largest Hmong population (48,189) in the United States and St. Paul (36,177) is the city with the highest Hmong population in the country.7 Altogether, Hmong Americans represent about nine percent of the county’s 550,000 residents, spread across sixteen cities. Minnesota’s Hmong population remains second to California (107,458) with Wisconsin in third place (62,331). In addition to St. Paul, three other cities have Hmong populations over 10,000. Two are in California (Fresno, 27,705 and Sacramento, 17,483) and one in Wisconsin (Milwaukee, 12,251).8

What contributed to the concentration of Hmong in Ramsey County? The early refugees found this region to be a place where the private and public sectors collaborated to support them. There were many obstacles to overcome for all involved, but what made the adjustment to an unfamiliar place manageable was the way in which individuals and organizations were committed to providing access and support to the refugees.9 The refugees, for their part, reached out to friends and relatives who had been resettled elsewhere and tried to encourage them to move to Minnesota. They knew that they could better support themselves and other refugees if they were in close proximity to Hmong already settled there.

As more Hmong people moved to St. Paul, they were able to advocate for interpreters and a plethora of support staff in schools, health care facilities, and workplaces. They soon established community-based organizations to provide basic needs support as well as education and training to newcomers. They started businesses that catered primarily to the Hmong population, participated in the U.S. political process to ensure they have representation, accessed resources to establish Hmong-focused schools as well as other nonprofit organizations, and hosted a wide range of community gatherings such as the Hmong International Freedom Festival held annually for more than four decades at Como Park’s McMurray Fields. Though the name of the event and specific activities have changed over time, sports competitions have been an integral part of the festival.

The critical mass has enabled the endurance of a vibrant community where Hmong culture and its traditions can also be sustained. As a result of the concentration of Hmong in Ramsey County, over time, Hmong American professionals of all fields from other locations chose to move to this area to use their expertise in service of the community. This phenomenon contributed to diverse socioeconomic experiences among Hmong in this region. In the early years of resettlement, few people lived outside of St. Paul. With a growing professional class, Hmong residential settlement expanded to suburban areas, as illustrated by the presence of Hmong Americans in most cities within Ramsey County.

Growing Up in Ramsey County

As I reflect on my experiences of growing up in St. Paul during the 1980s, I realize that we had so little, yet we managed to keep our heads high. Once I learned how to read and write, I immersed myself in books. It was a way for me to cope with everyday challenges. We were poor financially, but what we and many other refugee families like us had was that we were not deficient in love and community. What we have had to overcome to reach a place like the United States has made us resilient. As a teenager, I realized that I had access to opportunities that were unimaginable only a few years ago. If people like my parents and the thousands of people who had to be uprooted can keep going, then I had no excuse to not make something of myself. While remaining deeply committed to Hmong culture and traditions, my parents, You Yee Vang and Pang Thao, were openminded and supported my interests in and outside of the classroom.

In the mid-1980s, my family began seasonal gardening. Each spring, my parents went to order plants, buy the fertilizer, and other necessary supplies. Because of school, my four brothers, younger sister, and I only helped on weekends. As soon as school was out, we were obligated to work in the fields. While our classmates attended summer enrichment programs, we toiled the land with our parents. While our friends went swimming in the afternoons, we enjoyed fermented mustard green with a bowl of mov ntse dlej (rice in water) with our parents.

My summer Saturday mornings often went as follows. My parents got out of bed still fatigued but accompanied by a sense of excitement about the most financially rewarding day of the week—at the farmers’ market. They cracked the doors of our bedrooms and demanded, “Sawv os! Txug moos moog muag khoom lawm. Sawv tseeg!” Our minds responded, “OK, we’re coming,” but our tired bodies wanted to scream, “It’s only 5 a.m.! It’s summer vacation! We want to sleep for another five minutes. Just five more minutes, please!” Since we did not own the land we farmed, we had to bring the vegetables to our home in St. Paul and prepare them to sell the next day. Saturday was the busiest day at the St. Paul Farmers’ Market. Hundreds of prospective customers strolled through the aisles. Some came merely to enjoy the vibrant atmosphere, while others purchased fresh vegetables until their arms could no longer handle the weight.

Working on the farm was tiresome. But being in the country afforded us many experiences that one could not have in the city. For example, at the farm in Hugo, I asked my father to teach me how to operate a car. I was 14. He would let me drive from one end of the field to the other. As soon as I turned 15, I signed up for driver’s education. Just as he did to teach my mother and two older brothers to drive, my father filled milk containers with dirt from the farm. He would then get up early on weekends to take me to practice parallel parking at the Aldrich Arena parking lot. If there were cars present, then he would find another empty lot. At the empty lots, he inserted a branch inside each container high enough so you can see from inside the car. Then he placed the containers far enough from each other to parallel park.

As soon as I turned 16, I took my driver’s exam. During the first attempt, I was intimidated by the male examiner’s tone of voice—monotonous, uninterested. I was incredibly nervous that I turned right at a stop light where a sign said “no turn on red.” I failed. Over the years, each time I saw a “no turn on red” sign, it reminded me of my failure. I did pass on the second try. I loved to drive and fought my siblings to do so anytime I could. As a short person driving a van loaded with vegetables to the farmer’s market, I felt a sense of control. No matter how busy the market was, I always succeeded to parallel park.

As a student at Washington Junior High (now Washington Technology High School), I began to join extracurricular activities. I played volleyball and softball. My favorite sport was softball. I was an infielder (third base and shortstop) in seventh grade, and I was the pitcher in eighth grade. My love for the game earned me the “Slugger Award.” A fond memory was that my family rented the lower unit of a duplex in the Thomas-Dale neighborhood (a.k.a. Frogtown) that was owned by the legendary Minnesota Twins player, Tony Oliva. Every time he came to collect the rent I would serve as interpreter for my parents so that I could talk to Tony. He was always interested in what I had to say. Although he was retired from baseball at the time, he even got me autographs I wanted of Twins players Kirby Puckett and Kent Hrbek.

I attended Como Park High School for the first semester of ninth grade but then transferred to Johnson High School on the East Side once my family received a Section 8 voucher for a single-family home. It was the first such house we lived in, so my siblings and I were ecstatic. We had gotten used to moving, but I had hoped for some stability to finish high school with the friends I had made in middle school. I transferred in the middle of the school year with apprehension, but I became involved in several extracurricular activities immediately and made some new friends within a short period of time. I competed for and won leadership roles that allowed me to spearhead special projects. I did not know how to swim well, but I dared to join the Catalina Club, which was Johnson High’s synchronized swim team. Practicing for hours after school greatly improved my swimming skills. During my junior year, I participated in the Close-Up program, where I traveled to Washington D.C. to learn about the political process and visit many historical sites.

During my senior year, I received two recognitions that were defining moments for me as a young person. Since there were many other students who ranked much higher than I did academically, I initially did not think I would have a chance, but I decided to submit my essay anyway. When I was chosen as the 1989/’90 recipient of the Chief Justice Warren E. Burger/Edna Moore Writing Scholarship, it significantly increased my confidence. Justice Burger was an alumnus who started the scholarship in 1985 to honor his English teacher, Edna Moore. Regarding the second recognition, I was nominated as a Homecoming Queen candidate. At the time, Johnson High School was racially diverse, but the candidates always overwhelmingly consisted of our white peers. Although I did not win, I came in second and was the school’s first Hmong student to be Lady-in-Waiting. Due to some school violation by the queen, she was dethroned, and I became Homecoming Queen. In the grand scheme of things, it is such a small moment, but what it meant for me and the hundreds of Hmong students at Johnson High School was that we too belonged and had the right to claim our places in that space.

As one of the first few girls from my extended family to graduate from high school with grand plans to go to college, my parents held a soul calling ceremony for me. My father was a shaman. He performed the ceremony in the basement of our house on Luella Street. We did not have room in the main living area so his alter was in the basement. While he carried out the rituals, my mother prepared a bundle of white strings. The women relatives helped to prepare food. Before the meal, everyone present took turns to tie strings around my wrists wishing me good health and luck to achieve all my goals.

Lee Pao Xiong

Lee Pao Xiong is Director of the Center for Hmong Studies at Concordia University-St. Paul, a role he has held for nearly two decades. His prior roles included Director of Housing Policy and Development for the City of Minneapolis, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Urban Coalition, and Executive Director of the State Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans, the Hmong American Partnership, and the Hmong Youth Association of Minnesota.

My family arrived in the United States from Ban Vinai Refugee Camp on October 22, 1976. We initially settled in Menomonee, Wisconsin but moved to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1979 to be closer to my mom’s family. One of my mom’s cousins and stepbrother were among the first Hmong refugees to resettle in Minnesota. We lived in the North End neighborhood until 1982, then moved to McDonough Homes, a public housing project, and lived there until 1985. One of my best memories about living in the North End was waking up early on Saturday to stand in line at the Salvation Army store on East Seventh Street to dig through piles of free clothing. As I got older, I also recalled going to the Salvation Army store on University Avenue East in St. Paul to similarly sort through the piles of free clothes.

Growing up at McDonough Homes, we faced a great deal of racism. People did not know why we were there. There were lots of racial fights because many of us got picked on. For example, one day while I was taking out the trash, a kid threw a rock and hit me. I was furious, so I chased him to his house. His older brother came out and held me down while the kid who threw the rock punched me. I felt helpless and was hurt pretty bad. After that incident, I decided I would not allow myself to be treated that way again. As a result, I took up martial arts. At the time, Lao Family Community of Minnesota was in the YMCA building in downtown St. Paul. The YMCA allowed the theater to be used to teach martial arts for free. Many of us enrolled in the course were taught by Grandmaster Xay Long Yang. This building is no longer there. In its place is a parking ramp. I also have fond memories of my high school years when I was an active student. I was inducted into the Como Park Senior High School Hall of Fame in 1992.

In reflecting about Hmong experiences in Ramsey County over the last fifty years, I’m proud that the Hmong have contributed greatly to the political, economic, cultural, and education of this region. A notable achievement is political engagement. Choua Lee became the first Hmong person elected to public office in the United States when she won a St. Paul school board election in 1991, and we now have nine members of the state legislature who are of Hmong descent. The youngest person to be elected to the St. Paul City Council is Nelsie Yang. When May Chong Xiong was elected to the Ramsey County Board of Commissioners in 2023, she became the first Asian, the first Hmong-American, and the youngest to serve. Another contribution to the state is the Hmong population’s buying power, which exceeds one billion dollars. Finally, I am also pleased that we have two major Hmong shopping malls in Minnesota: Hmongtown Marketplace and Hmong Village.

MayKao Y. Hang, DPA

MayKao Y. Hang is Vice President for Strategic Initiatives and Founding Dean of the Morrison Family College of Health, University of St. Thomas. Dr. Hang’s former roles include President and CEO of the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation; Adult Services Director with Ramsey County Human Services; and Resident Services Direct with the Saint Paul Public Housing Agency.

Upon our arrival, we were resettled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in August 1976, and moved to St. Paul, Minnesota in September of 1978. We moved to St. Paul because my dad fell in love with the city after visiting earlier that spring. Our family included my mom, dad, three sisters, and a brother. We lived at McDonough Homes initially, but within three years bought a house in St. Paul. We were proud to be one of the first Hmong homeowners. All my siblings and I graduated from college, and three of us would go on to earn graduate degrees. I have great memories of being a student at Como Park Senior High School, where I played varsity tennis and participated in various other clubs. Highlights included winning “Rookie of the Season” in gymnastics and many high school debate rounds.

My fondest memories are being in meadows, parks, and lakes in St. Paul and Ramsey County: swimming during long summers at McCarrons Lake, fishing at Lake Phalen, and taking walks on Wheelock Parkway, and gardening with my mom. Unfortunately, I have no pictures of us doing these activities; we didn’t always have a camera during these early days in St. Paul.

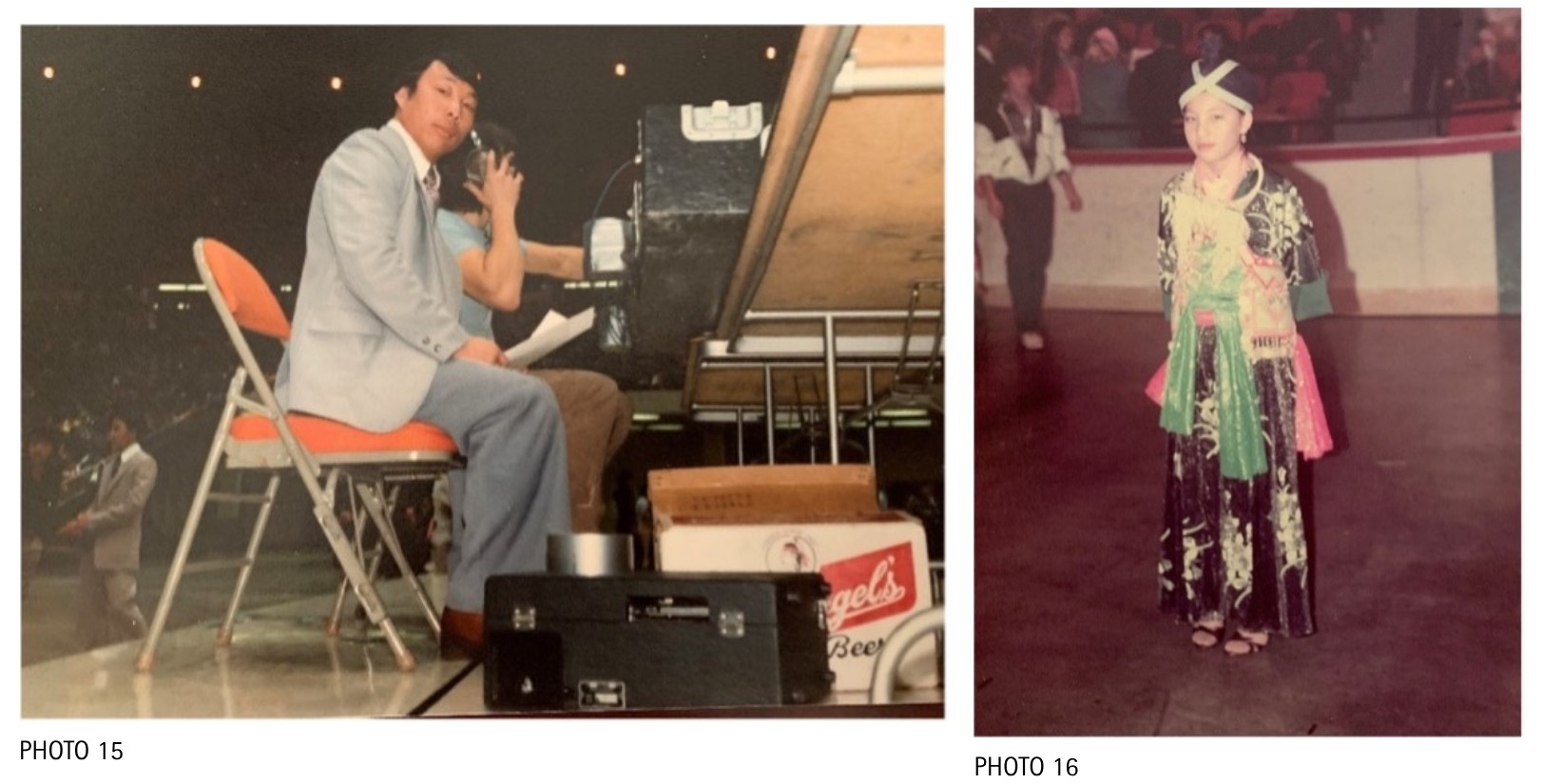

My family is service-oriented, and the other memories I have include my parents always being engaged in community activities to preserve Hmong culture and heritage. My dad, Blong Yang, was one of the co-founders of the Hmong New Year, Lao Family Community Center, the Hmong Youth Association, the Hmong Sports Festival, and the Hmong Cultural Center.

A picture of my dad in the early 1980s shows him working as he enjoyed the Hmong New Year from behind the scenes. He was monitoring the sound system and making sure all of us could see and hear the main stage. The Hmong New Year would become an annual get-together.

Overall, I am proud of the civic, economic, and educational contributions of the Hmong community in Ramsey County. The Hmong have helped fuel the growth and quality of life in Ramsey County. They are leaders, administrators, teachers, physicians, and deans. From humble origins, the Hmong have greatly increased their impact on society as Americans.

The Next Generation

It is undeniable that refugees, often fleeing conflict, persecution, or natural disasters, face incredible hardships as they embark on their journey to find safety. Arriving in a new country, they must confront language barriers, cultural differences, and the daunting task of rebuilding their lives from scratch. Despite these obstacles, many refugee groups like the Hmong exhibit remarkable resilience and determination. They draw upon their inner strength and the support of their communities to overcome adversity. The belief in the transformative impact of formal education has motivated the younger generation to realize their refugee parents’ dream of a better life. The many traditions that their refugee parents and grandparents brought with them have certainly changed over the course of the last five decades, but we have witnessed that through hard work, education, and the willingness to adapt, the Hmong community in Minnesota broadly and in Ramsey County specifically, has succeeded in contributing to this region in meaningful ways. Individuals like Sunisa (Suni) Lee, born to Hmong refugee children who grew up in St. Paul, serve as the embodiment of resilience and determination. As the first Hmong American gymnast to make the U.S. Olympic team and win an Olympic gold medal at the 2021 Tokyo games, and one gold and two bronze medals at the 2024 Paris games, her achievements have focused even greater positive attention on a community which, fifty years ago, knew little about Hmong people but opened their homes and community to welcome us.

Chia Youyee Vang is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where she also serves as Vice Chancellor for Community Empowerment and Institutional Inclusivity. Dr. Vang is an internationally known expert on Hmong history, culture, and contemporary life. She is author of four books: Prisoner of Wars: A Hmong Fighter Pilot’s Story of Escaping Death and Confronting Life (Temple University Press, 2020), Fly Until You Die: An Oral History of Hmong Pilots in the Vietnam War (Oxford University Press, 2019), Hmong America: Reconstructing Community in Diaspora (University of Illinois Press, 2010), and Hmong in Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008). In March 2016, the University of Minnesota Press released her co-edited volume, Claiming Place: On the Agency of Hmong Women.

NOTES

- Chia Youyee Vang, Hmong America: Reconstructing Community in Diaspora, University of Illinois Press, 2010.

- See Ken Levine, Ivory Waterworth Levine (Producers), Becoming American: The Odyssey of a Hmong Refugee (New Day Film, 1983); Christopher Robbins, The Ravens: The Men Who Flew in America’s Secret War in Laos (New York: Crown, 1987); Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1945-1992 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Roger Warner, Backfire: CIA’s Secret War in Laos and Its Link to the War in Vietnam (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); “The Hmong and the Secret War,” Valley PBS, May 6, 2021.

- Chia Youyee Vang, Hmong America: Reconstructing Community in Diaspora (University of Illinois Press, 2010); Jeremy Hein, Ethnic Origins: The Adaptation of Cambodian and Hmong Refugees in Four American Cities (New York: Russell Page Foundation, 2006); Lillian Faderman, I Begin My Life All Over: The Hmong and the American Immigrant Experience (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999).

- As an eight-year-old child, I remember only bits and pieces of how my family escaped from Laos in 1979. Much of what I know has been informed by my research in western countries where Hmong resettled and in Southeast Asia. As a historian, I have spent the last two decades sifting through archival materials and conducting interviews with hundreds of veterans and civilians who had been driven to fight in and for their villages and towns.

- Mark Pfeifer, “Hmong Population Trends in the 2020 U.S. Census,” Hmong Studies Journal, vol. 26, no. 1 (2024), 1-12.

- Pfeifer, 8.

- Pfeifer, 9.

- Pfeifer, 8.

- Chia Youyee Vang, Hmong in Minnesota, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008.

- Hmong Studies Journal, Hmong Census Data analysis. https://www.hmongstudiesjournal.org/hmong-census-data.html.

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2025

- Creators

- Chia Youyee Vang, PhD

- Topics