Ramsey County History Winter 2024: H. Emil Strassburger

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 58

- Issue

- 4

- Creators

- Nicole Foss

- Topics

Volume 59, Number 1: Winter 2024

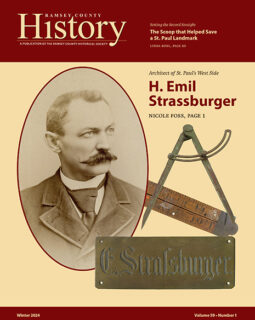

Architect of St. Paul’s West Side: H. Emil Strassburger

Author: Nicole Foss

Architectural Historian Nicole Foss grew curious about some of the old houses she passed on daily walks in her neighborhood. Curiosity led to research, which evolved into our cover story “Architect of St. Paul’s West Side: H. Emil Strassburger.” Very little has been published on the German immigrant Strassburger—until now. Most of the business blocks he designed in the late-nineteenth century are long gone, but several residences still stand tall along the West Side bluff. Strassburger’s architectural contributions to this neighborhood are significant. Foss describes Strassburger’s work and his willingness to experiment with the styles of the day, including the Richardsonian Romanesque style, brick interpretations of Stick style with Eastlake embellishments, and at least one exploration in Second Empire-inspired eclecticism.

Image of H. Emil Strassburger courtesy of John Riley.

Nearly thirty years into Minnesota’s state-hood, St. Paul was undergoing a building boom. By the mid-1880s, the economy had rebounded in the aftermath of the American Civil War and the Panic of 1873, fueling an influx of new residents and the construction of buildings to house and employ them. Keeping pace with the rest of the city was the West Side. A relatively new addition to the capital city, the neighborhood, located southeast of St. Paul proper, was so named because of its position on the west side of the Mississippi River from the perspective of steamboats traveling north.

German-trained architect Heinrich Emil Strassburger entered the milieu of the West Side’s rapid growth by way of San Antonio, Texas, in 1884. He brought with him formal European training, an eagerness to make his mark, and a willingness to experiment with the styles of the day. Strassburger is notable as the only formally trained architect to base his practice in the West Side during the neighborhood’s largest period of growth from the mid-1880s to the late 1890s. He is also recognized for several distinctive residential designs that remain as part of the Victorian-era architectural character of the West Side bluff today.

Strassburger designed commercial, residential, industrial, and municipal buildings throughout his career, which included an early stint in San Antonio, fifteen years in St. Paul, and nearly a decade in Crookston, Minnesota. While less than a third of his buildings in St. Paul are extant, most that remain retain fair-to-good integrity and reveal his masterful designs. These feature the Richardsonian Romanesque style, brick interpretations of Stick style with East-lake embellishments, and at least one exploration in Second Empire-inspired eclecticism. Strassburger’s skillfully designed buildings are visually dense yet energized by balanced asymmetry and lively ornamentation.

West Side Roots

When Strassburger, his wife, Amalie, their three-year-old daughter Gertrude, and infant son Richard arrived in St. Paul in 1884, the West Side had been added to the city only a decade earlier. Previously part of Dakota County, the land comprising the neighborhood was annexed in 1874, and the toll was abolished for the Wabasha Street Bridge, which connected the city to its newest neighborhood across the Mississippi River. The area’s geography has charted its development. To the north are the low-lying Flats, prone to frequent flooding, while rising to the south with a steep increase in elevation is the sandstone bluff. A mix of industries, railroad facilities, single and multifamily immigrant housing, and a commercial district characterized the Flats. The bluff was largely residential.

By the mid-1880s, the Flats were ethnically diverse, featuring a large concentration of Jewish residents who had fled the pogroms in Eastern Europe and settled among French Canadian, Irish, and German arrivals, along with some Dakota who had returned to their homeland following their forced removal in the aftermath of the US-Dakota War of 1862. In the early twentieth century, Mexican immigrants, Syrians, and Lebanese arrived, as well. Expedient residences sprouted up among the industries that sprawled across the Flats in contrast to a few stately limestone houses that remained from early well-to-do arrivals. The hodgepodge of residential and industrial land on the Flats was bisected by two main commercial throughfares that run northwest to southeast—Wabasha Avenue South (originally Dakota Avenue) and Robert Street South. They were knit together by perpendicular cross streets named after states. Over the next fifteen years, Strassburger’s architectural designs would help shape the built environment of Wabasha and Robert Streets South and both the Flats and the bluff.

Strassburger joined a growing number of professional architects gradually succeeding the city’s original master carpenters and masons. German architects predominated among the arrivals of the mid-1880s. Albert Zschocke, born in Zwickau, Saxony, arrived in 1883, the same year as Emil Ulrici, the American-born son of a German father and American mother. Strassburger followed in 1884, and German-born Hermann Kretz arrived in 1886. Among the city’s formally trained architects, Strassburger was the only one to base his practice in the West Side.

Saxony to San Antonio

Strassburger was born to Heinrich Ferdinand, a bricklayer foreman, and Louise Emilie Biesolt on July 11, 1853, in Bautzen, Saxony. Bautzen, known for its intact medieval architecture, is located near the borders of the Czech Republic and Poland, close to Dresden. Strassburger joined older brother Friedrich Oskar, while younger brother Paul followed three years later. Emil and Paul, the only members of the family to immigrate to the US, would remain close throughout their lives. Strassburger received formal architectural training in the early 1870s, although the institution he attended has yet to be identified. On September 18, 1877, he married Marie Amalie Pötschke at the Cathedral of St. Peter in Bautzen. Daughter Gertrude was born in Germany in 1881. Other children would eventually join the family—Richard (Texas, 1884), Henry (St. Paul, 1885), and Ella (St. Paul, 1888). In 1882, at the age of twenty-nine, Strassburger immigrated to America. The following year, his wife and daughter arrived, as did Paul.

The family first settled in San Antonio with Paul as a boarder. Paul found employment as a carpenter, and Emil was hired as a draftsman for Wahrenberger and Beckmann. The firm was founded in 1883 as a partnership between Albert Felix Beckmann, a San Antonio-born, German-trained architect, and James Wahrenberger, an Austin, Texas-born architect who had studied at the Polytechnic in Karlsruhe, Germany. Both Wahrenberger and Beckmann were Strassburger’s contemporaries in age.

It was not long before Strassburger struck out on his own; by January 1884, he had established an office at 245 Market Street in San Antonio. However, the family’s time there was short-lived. Within a year, they had relocated to the rapidly growing West Side neighborhood of St. Paul with its large German community. Paul followed a couple of years later.

Setting Up Shop

In St. Paul, Strassburger entered the economic and social spheres. He established his architectural practice in a business block along Wabasha Street South, the commercial gateway to the West Side. The two-storefront block was owned by Mathias Iten, a hardware dealer and early West Side resident. Strassburger took on the position of commander for the local lodge of the Ancient Order of United Workman, a fraternal benefit society. He also formed business partnerships. For a short time during his first year, Strassburger partnered with Jacob R. Steiner, a real estate agent and later newspaper manager and editor who worked briefly as an architect. However, they soon parted ways. Steiner’s name did not accompany Strassburger’s on any building permits from this time. Other ventures included the acquisition of real estate with men such as August Jobst, a blacksmith and another early West Sider, and Paul Martin, a prominent real estate developer.¹⁰

Strassburger’s first-known design in St. Paul was a three-story commercial block for Dr. George Marti, a pharmacist, on Wabasha Street South. The first floor of the building housed Marti’s prescription and sales rooms. The second floor housed offices for medical and legal professionals, and the upper floor included a public hall where fraternal organizations met. Strassburger’s design featured entranceways framed by polychromatic pointed arches on the first story and segmental arched windows with polychromatic window hoods on the second story. The building was topped by an ornate, galvanized-iron cornice with diamond-shaped ornament s at the corners, a half-round pediment supported by brick pilasters, and a sawtooth brick pattern below the cornice. Strassburger provided clear visual delineation between the stories with a belt course. He often emphasized the most visible corners of his commercial designs by accentuating them with an ornate bay window, turret, or tower. In this case, there was a canted two-story bay window at the intersection of Wabasha Street South and Fairfield Avenue.

Business is Booming

It was not long before Strassburger received affirmation that his decision to relocate to the West Side was sound. Several clients and commissions followed on the heels of the Marti Block project. Strassburger designed at least nine buildings in the neighborhood—including business blocks, stores, and two residences—in 1885 alone. Eight of these were on the Flats, with one residence on the bluff. Another early business project was the Lawton Block, designed in 1885 for brothers Albert M. and Charles B. Lawton, who owned a real estate, loan, and insurance company. The three-story brick building, which housed the Lawton Brothers and the West Side Bank on the first floor, was described as “very handsome and substantial” in Northwest Magazine. It included features found on the Marti Block—most notably a corner turret with an octagonal roof and segmental arched windows with polychromatic hoods. The windows on the elevation facing Wabasha and one bay of windows facing Chicago Avenue featured light-colored stone window hoods, which contrasted stylishly with the dark color of the brick walls.

Strassburger’s commercial commissions on the Flats continued at a brisk pace through the mid-1880s. His office was located in the Iten Block, which originally consisted of two store- fronts (numbers 88 and 90), designed by Ulrici in 1884. In 1886, Iten hired Strassburger to create a third storefront on the lot to the north, cementing the architect’s presence and serving as an additional bricks-and-mortar advertisement for his work.

That same year, developer Martin hired Strassburger to design a large commercial block adjacent to the Colorado Street Bridge along Wabasha Avenue South. The three-story brick block, known as Amity Hall, contained several businesses along with auditoriums where performances were held and benevolent societies met. As with Strassburger’s other commercial designs, the Amity Hall block featured a canted corner at the intersection of Colorado and Wabasha.

Strassburger designed another block for Martin in 1887 on Robert Street South, just north of the present-day intersection with Cesar Chavez Street. This two-story brick commercial building exhibited a profusion of ornamentation, including polychromatic window hoods over alternating semicircular and segmental arched windows, brick panels, and a series of circular and triangular pediments alternating with turrets supported by brick corbels.

To accommodate his thriving business, Strassburger soon began employing draftsmen. His work was attracting wider attention, as well. In 1886, Northwest Magazine highlighted several of his designs, including the six-storefront Fitzer Block, proclaiming,

Much of the attractive and well designed architecture of the West Side has been the result of the skillful work of E. Strassburger. . . . His busy office at 88 Dakota Ave., is a favorite resort for information concerning the desirable business locations and residences of the West Side.

The Razing of the Flats

Over half of Strassburger’s designs were constructed on the Flats, however, none would survive beyond the mid-twentieth century. By the early 1950s, the Flats neighborhood was home to a vibrant multi ethnic community. While most families faced poverty and lived amid active industrial properties, the enclave was close knit and enjoyed a strong sense of community, with its own churches and synagogues, schools, corner stores, and neighborhood institutions.

One of the most challenging aspects of living on the Flats was spring flooding. In 1952, a historic flood brought significant destruction to the neighborhood. In 1956, the St. Paul Port Authority announced that it would raze the businesses and residences on the Flats and convert the area to an industrial park. Over 2,000 people were removed from their homes, and almost 500 buildings were demolished, including those Strassburger had designed. In a painful irony, a flood wall was built in 1964 to protect the industrial park that replaced the former community.

Homes on the Bluff

To view Strassburger’ sextant work in St.Paul, one must visit the West Side bluff. In 1886, he designed two houses there which employ similar forms and detailing. The first (right) he built for himself and his family, which by 1885, had grown with the arrival of son Henry. He designed the other house (not pictured) for Andrew Schletz, a brick manufacturer. Both two-story brick homes feature an offset projecting front gable with a paired window surrounded by ornamentation, including shingles and horizontal stickwork. As with Strassburger’s commercial designs, the division between the stories is accentuated by a stylized brick belt course. Segmental arches cap the windows. Each front gable originally featured a decorative truss form and vergeboard, which have been lost to the ravages of time and reroofing.

That same year, Strassburger designed a home for Anton W. Mortensen, deputy clerk of the Board of Public Works. This two-and-a-half story brick house has clipped gables on an already complex roofline. Brackets line the eaves, and the offset front gable features a bay window topped by a pediment with a sunburst design. On the east elevation is a two-story bay window also topped by a pediment. Strassburger accentuated the visual division of the first and second story with a decorative belt course and topped the segmental arched windows with ornate hoods. The crowning glory is the Eastlake detail in the front gable. In addition to decorative shingles, there are recessed wood panels, incised and fluted pilasters, a small central semicircular pediment with a star motif, incised vergeboards, and a distinctive wood cartouche.

Strassburger briefly experimented with Second Empire-inspired eclecticism through the 1886 design of a category-defying brick carriage house for Edward J. Heimbach, a boot and shoe dealer. Relatively diminutive though the structure is, a suggestion of two stories is accomplished through the corbeled belt course. The roof straddles between hipped and mansard, while the building boldly asserts its presence through a central projection capped by a pyramidal false dormer and dentils. It is flanked by two towers on either end. Fenestration comes in a variety of forms—bullseye, rectangular, segmental arched, and round top—with molded surrounds on the latter.

Architectural historian Larry Millet described it as “one of the most delightful buildings of its kind in St. Paul.” The Heimbach house itself (not pictured) is an extremely handsome example of Victorian-era architecture, but whether Strassburger can lay claim to that design as well is yet to be determined—the architect line on the building permit was left blank.

By 1890, Strassburger had turned away from Eastlake, which was no longer in style, and embraced Richardsonian Romanesque. Two residences that exemplify this style, at different scales, include the house at 412 Wyoming Street West (1890) and the Dr. Octavius Beal House at 23 Isabel Street West (1891).

The home on Wyoming is an elegant example of a modest but full expression of the style. This two-and-a-half story brick edifice features a two-story corner tower with a conical roof and rusticated bands of stone sills and lintels. The gables boast decorative shingles and stickwork in a half-timber style, while the pedestrian entrance on the facade has a round arch with a half-round transom and double-leaf door.

The following year, Strassburger expanded further on the Richardsonian Romanesque style with a residence for Dr. Beal. The Beal House, located on the edge of the bluff along Isabel Street, commanded quite a view, both to and from the property when it was constructed, although its facade is now screened by trees. This brick structure, notable for its complex massing, has a corner tower with a conical roof with bracketed eaves, a three-part window in the gable surrounded by decorative shingles, and belt courses of rusticated stone dividing the two stories of the house. The entranceway features a round arch with a half-round transom in true Richardsonian Romanesque style.

In addition to designing single-family homes, commercial buildings, and duplexes, Strassburger also designed rowhouses. In 1891, John Grover Wardell, manager of the Spa Bottling Company on the Flats, commissioned Strassburger to create the eight-unit building which became known as Grady Flats. Its brick facade features alternating projecting bays, including a central bay capped with two tourelles flanked by two octagonal-roofed turrets. Each projecting bay is bedecked with a graceful wood porch, while the recessed bays of the facade are anchored by broad, segmental arched windows with polychromatic accents of light-colored keystones and springers.

Coda to a West Side Legacy

In an 1888 book on St. Paul’s industrial growth and commercial development, Strassburger was described as “the only architect of note on the west side of the river [who] has designed and superintended the construction of many of the best blocks and residences in that section of the city . . .” By 1899, he had designed at least thirty buildings in St. Paul, nearly all in the West Side neighborhood.

EASTLAKE ARCHITECTURE

Emil Strassburger’s work in St. Paul exemplified several different architectural styles over the years. Examples of his extant work in the West Side include Eastlake and Richardsonian Romanesque styles. He even dabbled in an eclectic interpretation of Second Empire. (See the Edward J. Heimbach Carriage House at 64 Delos Street West.)

The term Eastlake can be used to refer to an architectural style, a characteristic type of ornamentation found on other styles of architecture (most commonly Stick style), and a broader aesthetic movement that includes furniture and home decor. The term comes from the surname of Charles Locke Eastlake (1836–1906), a British furniture designer and architect by training. Eastlake rejected the mass production of what he considered low-quality imitations of the then-popular French Rococo furniture, which was ornate and full of scrolls and curlicues. Instead, he advocated for a return to more geometric Gothic-inspired design. While his furniture was influenced by Gothic Revival architecture, it was not long before his immensely popular designs, which featured pierced and incised motifs in wood, were, in turn, inspiring architecture, specifically in America.

Eastlake’s passion for Gothic Revival had a counterpart in Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852), an American landscape designer and author whose publications on architecture were wildly popular during the mid-to-late-nineteenth century. Downing, too, was a strong promoter of Gothic Revival over the then-popular Greek Revival style. He emphasized “truth” in architecture. A house should look like a house, not a Greek temple. Downing preferred stone as a building material, but if one had to build in wood, the material should be emphasized rather than disguised. Downing embraced this to such an extent that the house designs he helped popularize began to showcase the properties of wood as a material and symbolically represent the internal wood framing of the houses on the exteriors.

This took the form of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal beams and sticks arrayed across the exterior of houses. The applied stickwork visually divided the stories of the house, echoing the internal wood frame and was most ornate in the gables, where symbolic trusses complete with kingposts, rafters, collar beams, tie beams, and struts were featured. These embellishments characterized what came to be known as Stick style. In addition to the characteristic “sticks” on the exterior walls, the eaves, gables, and windows of Stick-style houses were ornamented with boards that had been scroll-sawn and incised with geometric and stylized organic shapes and, often, Gothic motifs. In time, this wood architectural ornamentation, which echoed elements of furniture inspired by Eastlake’s designs, became associated with Eastlake’s name.

As popular as Stick and Eastlake were, few intact buildings with the style remain. The ornamentation was subject to deterioration from the elements, as well as intentional removal when it fell out of style. Decorative vergeboard, trim, and stickwork disappeared with the replacement of roofs, windows, siding, and the enclosure of porches.

Strassburger’s work does not fit neatly into the Stick style with Eastlake ornamentation category because of his preference for brick as a construction material and the Germanic density of his designs. However, his Eastlake details exemplify a constrained exuberance that delights the observer, especially in the Anton Mortensen House.

Additional Information

Glossary of architectural terms noted in this article PDF

Map of buildings designed by H. Emil Strassburger on St. Paul’s West Side

Chart of H. Emil Strassburger’s structures on St. Paul’s West Side

Link to download full issue of Winter 2024 Ramsey County History magazine

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 58

- Issue

- 4

- Creators

- Nicole Foss

- Topics