Rondo Recreation in the St. Croix River Valley, 1909-1977

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 3, Summer 2024

- Creators

- Haley Prochnow

- Topics

By Haley Prochnow

The thermostat is set at 55°F during the winter in the Baker Land and Title Company building to keep energy costs low. I sit in what once was Harry D. Baker’s office wearing my coat and hat, digitizing donated photographs, letters, and paper ephemera from past residents of St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin. The St. Croix Falls Historical Society rents this building from the city. It houses our collections, a reading room, and exhibits dedicated to its time as a land management office. The 1882 Queen Anne-style structure with East Lake flourishes resembles a slice of wedding cake wedged onto the corner of State and Washington streets.

The building was once the administrative center of white settlement and colonization in the St. Croix River Valley. It was constructed as the Cushing Land Agency by St. Paul architect Abraham M. Radcliff in 1882 to manage acreage, natural resources, and landholdings gained through the Morrill Act of 1862. Years earlier, through the terms of this legislation, Caleb Cushing, an attorney and former US congressman from Massachusetts, was granted 36,000 acres of timberland along the St. Croix River. He paid $1.25 an acre. Money earned from land grants was meant to establish public colleges, providing opportunities to farmers and other working people. Some opportunists misused or loosely interpreted the terms of this system.

Maj. John S. Baker worked as Cushing’s land agent starting in 1869 and assumed control of the company around 1887. Harry Baker joined his father in 1893. The pair changed the name to Baker Land and Title Company in 1911 and operated the business as a real estate brokerage.

The younger Baker was responsible for hundreds of recreational land transactions. As travel to Wisconsin from Minneapolis, St. Paul, and other Midwestern cities became more convenient, he focused on lake and riverfront investments. He subdivided and platted land and advertised the properties in newspapers in the Twin Cities, Des Moines, and Chicago. In a 1950 interview, he noted:

“Our principal asset, in my humble opinion, has been the fine, sound, wholesome business principles of my father for reliable dealing and truthful representations in all of our business.”

Like his father, the Baker son carried on those principles. However, some of his practices would be illegal today. Rumored to be a taskmaster, Baker oversaw the work of his employees until age ninety-two, retiring in 1966. According to local historians, he insisted staff follow a singular rule: no property should be sold to a Jewish or Black person.

Yet—this research examines instances of recreational land purchased by Black families from St. Paul’s Rondo community in the St. Croix River Valley. In the first half of the twentieth century, Rondo was a mixed-income neighborhood with a prospering middle class—home to 80 percent of the city’s African American population. These few stories exist within the context of a time in Minnesota history where racial covenants were written into deeds, and real estate purchases limited where nonwhite residents could live.

The first racial covenants existed in Minnesota as early as 1910 and stipulated:

“. . . premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.”

Later, real estate companies duplicated this exclusionary language in thousands of deeds throughout the Twin Cities, creating segregated neighborhoods. New racial covenants were deemed illegal in 1953, but they were not completely prohibited until 1962 in Minnesota and 1968 nationally.

The families highlighted here were prosperous despite this reality. Beyond homeownership in St. Paul, they built equity in recreational land purchases within the St. Croix River Valley. Their stories exemplify the larger narrative of the Black struggle to own property, enjoy the rewards of their labors, and practice social mobility in post-Civil War America, during the Great Migration, and after.

Camp DuGhee on the Apple River, 1909-1920

Fredrick McGhee was born into slavery in Mississippi during the Civil War to Sarah Walker and Abraham McGhee. The family escaped the John A. Walker Farm in 1864 with help from Union troops. From Mississippi, they traveled north to Tennessee.

McGhee’s education started at a “freedmen’s school” and continued with two years at Knoxville College. He practiced law briefly in Chicago before moving to St. Paul in 1889, becoming Minnesota’s first Black lawyer. McGhee, his wife, Mattie, and their daughter, Ruth, were community leaders, influencing intellectual, social, and political circles. They lived at 665 University Avenue in a grand, three-story home. He was a prolific writer, speaker, and noted criminal defense lawyer as well as a pioneer in handling early desegregation and civil rights cases.

McGhee represented Minnesota in the National Afro-American Council (NAAC) at the turn of the century. Through this organization, he befriended W. E. B. Du Bois. His friendship with Du Bois, an early American civil rights activist, sociologist, socialist, and historian, led to the formation of the Niagara Movement (1905)—the forerunner of today’s NAACP (1909).

For the Love of Nature

While McGhee’s work and civic life were central, friendships and family were equally important, as was the time he spent outdoors. As early as 1889, he enjoyed angling adventures on lakes Sturgeon and Pokegama in east-central Minnesota. He vacationed with close friends, including Dr. Valdo Turner, a prominent physician, and Jose H. Sherwood, a postal clerk. Sherwood and McGhee were two of five people to pledge start-up funds for the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, which Du Bois edited for twenty-four years.

McGhee’s apparent love of nature drew him and his wife to Polk County—in the St. Croix River Valley—seventy-five miles from St. Paul. In 1909, they purchased thirty-nine acres along the Apple River near Amery, Wisconsin, for $1,500. The couple acquired farming equipment and livestock. The land, “came with a little rustic frame house, and the McGhees spent most of the next three summers there.” They playfully called their retreat Camp DuGhee—a combination of the last names Du Bois and McGhee. It made sense, as Du Bois visited when he was in Minnesota, as did others. Critical discussions on race, politics, and, perhaps, early principles of the NAACP were likely incorporated into fishing, farming, and enjoying nature’s solitude.

Guests Galore

A regular rotation of Black society spent time there. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams and his family visited the McGhee home and farm on occasion. Williams was one of three Black physicians in Chicago in the 1880s. Appointed to the Illinois State Board of Health in 1889, the skilled surgeon developed medical standards and hospital rules to combat prejudice in medicine. In 1891, he founded Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses.

Other guests included Julius Avendorph—the “Society Prince” of Chicago—and his family. Avendorph worked for the Pullman Palace Car Company and edited the society page of the Chicago Defender. He also formed multiple social and civic clubs for Chicago’s Black elite. His flawless style and respect from the community earned him the title of aristocrat.

Another close friend and fishing companion was Frederick D. McCracken, a real estate entrepreneur, founding member of The Sterling Club, and an early housing-equity activist from St. Paul. McCracken moved to Harlem in 1930 as head of operating staff and organizer of the Dunbar Forum at the Paul Lawrence Dunbar Apartments, where the Du Bois family lived. This facility, funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., served as a housing cooperative for Black families and was important during the Harlem Renaissance.

Many people enjoyed their retreats with the McGhee family, including McCracken and Du Bois, who noted:

“I remember camping with him [McGhee] one summer on the Apple River, Wisconsin, and his clients swarmed over the countryside and with boats invaded the lake where he was fishing in order to consult him. Around the campfire, he used to tell us extraordinary stories of his adventures.”

A Brief Respite

Unfortunately, McGhee’s years at Camp DuGhee were few. In September 1912, he died due to complications from a leg injury he sustained on the farm. He was fifty. The community celebrated McGhee’s life at St. Peter Claver Catholic Church and, a week later, at Pilgrim Baptist Church. There, the auditorium overflowed with friends, colleagues, and admirers. At the service’s end, mourners sang, “We Shall Meet Beyond the River” to honor this leader. It was an appropriate selection, given the lawyer’s connection to the river and enjoyment of the outdoors.

After his sudden death, Mattie and Ruth frequented the farm for the solitude it offered. However, in the 1920s, they followed other Black Americans to Washington, DC, and, later, New York City. Du Bois helped mother and daughter obtain apartments within the Dunbar complex in 1927, where Mattie resided until her death in 1933. Ruth worked as a stenographer and grew close to the Du Bois family, particularly their daughter, Yolande. Ruth lived at the apartments until the 1950s, when she moved to a little house at 303 Charles Avenue back in St. Paul.

If you drive to Lincoln Township in Polk County, you can cross the Apple River over a tiny bridge that leads up to what was once Camp DuGhee. Peeking between the modern cabins that fill the shoreline like a mouth of overcrowded teeth, it is still possible to envision the serenity of the land and the wide bend of the river where McGhee fished with friends—a place that probably once felt like total freedom. McGhee’s connection to this place that now offers no trace of him enhances our understanding of the St. Croix River Valley’s significance as an influential backdrop for progressive American thought leaders and social pioneers and how they have been underrepresented in history.

The St. Croix Valley Country Club, 1956-1962

The first known mention of the St. Croix Valley Country Club appeared in a Kansas City, Missouri, newspaper in 1956:

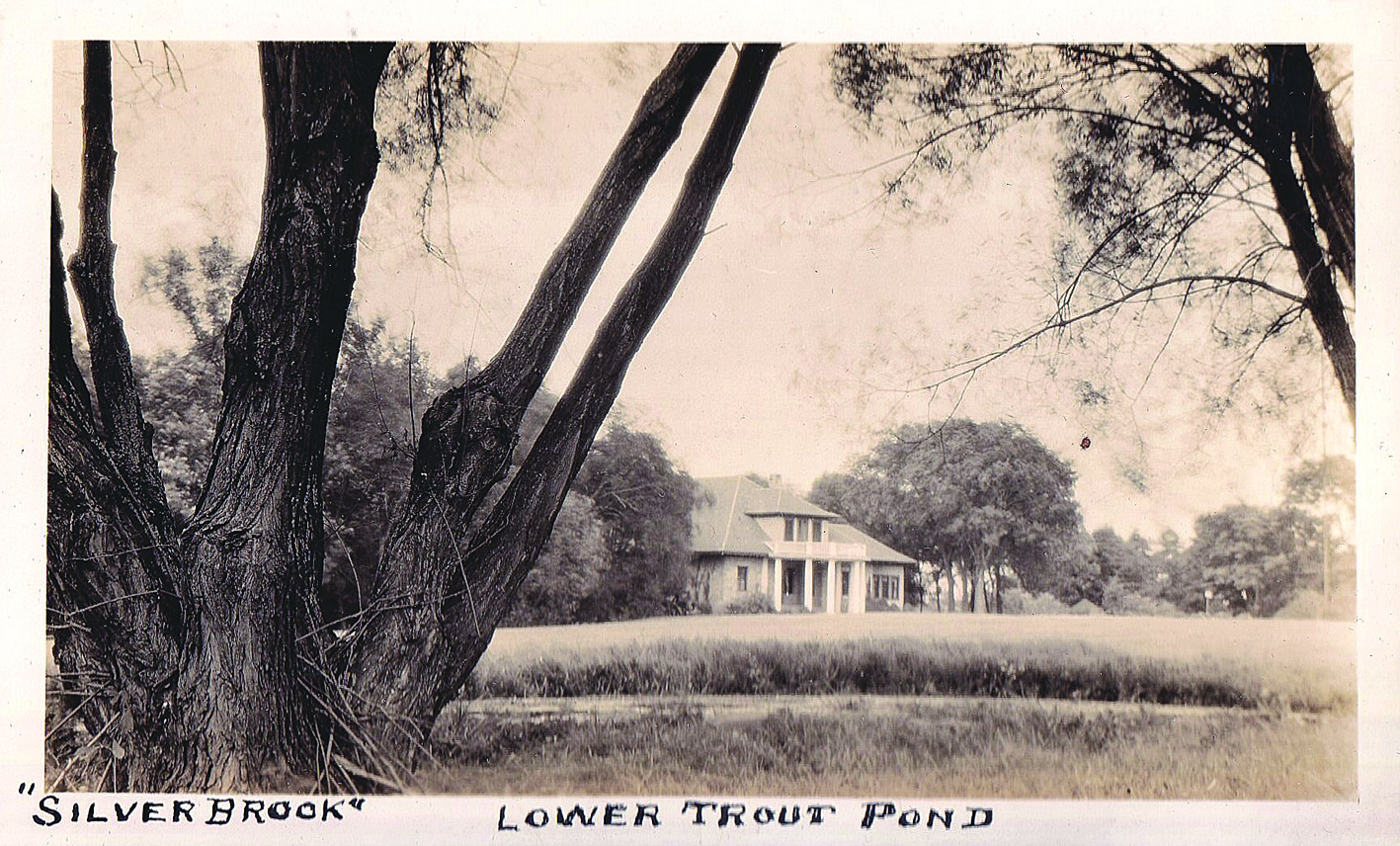

“Mr. and Mrs. James Rideaux, 707 Rondo Ave., have purchased an 11-bedroom lodge on the lovely St. Croix Riber [sic], at Osceola, Wis., 48 miles from the city. The estate has 200 acres and will be remodelled [sic] for all out-door sports.”

The property, known locally as Silverbrook, was a defunct copper mining venture and adjoining summer estate of St. Paulites Hezekiah and Fannie Holbert (built 1895). More recently, it served as a Swiss-style ski resort that sat empty for a few seasons before Anna Belle and James Rideauxs’ dream of owning, renovating, and operating a country club was realized. Shortly after purchasing the property, the couple organized an open house. Three hundred attendees from St. Paul and Minneapolis visited over a December weekend. “The guests were served refreshments in the spacious ballroom from a long Chinese antique table of teakwood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl.” Rondo pianist, Harriet B. Gordon, and her pet bird, Nehru, entertained. The club featured nineteen rooms total and sat high on a bluff overlooking Silverbrook Falls and the St. Croix River.

From 1956 to 1962, the Rideauxs’ St. Croix Valley Country Club served as a satellite meeting place for Rondo-based social and civic clubs, including the Cameo Social Club, Credjafawn Club, and the Twin City Forty Club. These organizations were founded in the early twentieth century, in part, because Black St. Paul residents were usually unwelcome in white society and prohibited from patronizing many of the city’s establishments. Instead, residents gathered at the Hallie Q. Brown Community Center, churches, and in living rooms and backyards. The Wisconsin venue was an enviable escape from the city. A weekend there could include socializing, hiking, fishing, hunting, archery, or an ongoing game of pinochle with Anna Belle on the back porch overlooking the falls.

The Rideaux Family

Anna Belle and James Rideaux were business owners, civil rights activists, socialites, and residents of St. Paul’s Rondo community. They were both born in 1906 in southern states—James in Lake Charles, Louisiana; Anna Belle in Birmingham, Alabama. They did not meet until they each ventured to Minnesota in search of opportunity. Anna Belle said goodbye to Alabama around 1930 and moved here with her baby daughter, Muriel, and her mother. James came north from Kansas City that same year. The couple met in 1933 and married in Chicago on February 18, 1935.

James, educated in business and tailoring at Kansas Vocational College, found work in St. Paul’s white, high-end establishments, including the University Club and Town & Country. In the 1950s and ’60s, he was a redcap night captain at Union Depot. He used his position to help Black travelers find safe lodging, often sending them to Rondo, where Anna Belle ran a boarding house for travelers. Years later, St. Paul Mayor George Latimer honored James’s commitment to service and community by declaring September 26, 1978, “James Rideaux Day.” After James’s death in 1990, he was given the Roy Wilkins Award for his civil rights work.

Shortly after moving to Minnesota, Anna Belle’s name started appearing in the society columns of the St. Paul Recorder and Minneapolis Spokesman. She was a gifted seamstress and taught community homemaking and sewing classes at Hallie Q. Brown and Welcome Hall. Anna Belle joined the Order of the Eastern Star, St. Anthony Hill Garden Club, the St. Paul Urban League, and was a founding member of the Cameo Social Club and an NAACP Housing Committee cochair for the organization’s national convention in 1960. In 1963, she owned and operated a dress shop in Minneapolis.

For twenty-two years, the couple hosted friends, family, and community to their home on Rondo Avenue. However, in 1959, they were forced to relocate when the city and state began preparing for the construction of Interstate 94 and the demolition of much of the neighborhood—700 homes and 300 businesses. Residents were inadequately compensated for their properties. Ultimately, the initiative led to a massive loss of wealth, public space, and culture. Families and business owners watched in despair as all they worked for was systemically destroyed. The St. Paul Recorder announced the Rideauxs’ move:

“Come December 1, Mr. and Mrs. James Riddeaue [sic] of 707 Rondo Av., will be greeting their friends in their newly decorated and remodeled home at 765 Marshall Av.”

It was during this stressful, anxious time, that the couple opened the doors to their Wisconsin retreat. Their work in providing a place of rest, relaxation, and community was more important than ever.

A Place to Relax; A Place to Organize

The St. Croix Valley Country Club was home to occasional NAACP chapter meetings and celebrations. For example, on January 20, 1957, the St. Paul Branch of the NAACP installed new officers there. The topic of the evening was “Moral Aspects of Segregated Housing.” Two notable attendees were Rev. Floyd Massey Jr. and Rev. Denzil A. Carty. These clergymen were local civil rights activists and leaders who fought for equity in housing, public schools, and the workplace.

The day after NAACP members met at the country club, Rev. Massey was formally inducted as chair of the Minnesota Protestant Pastors’ Conference in St. Paul. Among the guests was Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who spoke at the ceremony.

In looking at these two events, it becomes clear that the struggle for civil rights was very much alive in Minnesota and Wisconsin and had gained tremendous momentum by 1957. Clearly, the Rideauxs’ club housed crucial discussions and leaders of this movement during its most critical time.

It was also a place of Black excellence, luxury, and respite. For example, from 1957 to 1961, the Cameo Social Club held events like charm school, luncheons, and slumber parties at the retreat. The club even chartered a bus to transport its young debutantes from Rondo to spend a few days at the venue a week before the group’s culminating cotillion ball. The cotillion program was the first of its kind in the Upper Midwest. Many debutantes in Anna Belle’s care went on to impactful careers and service to their communities. For example, Joyce Ann Hughes, a Carleton College undergraduate and University of Minnesota School of Law grad (the first Black woman to achieve this honor in 1965), recently retired as a longtime law professor at Northwestern University.

A Short-Lived Dream

While James and Anna Belle worked hard to establish their country home-away-from-home, their work and community were in St. Paul. The distance between the two locations proved to be challenging, and, as Rondo splintered to make way for the interstate, the couple lost the beloved Wisconsin property to foreclosure in 1962.

A Los Angeles-based real estate developer purchased the property. Vandals cut a hole in the roof before the developer hired a local family to live in and maintain the home. In 1970, the developer sold the estate to the State of Wisconsin. Once again, it sat vacant. The state could not justify the expense or the complications to maintain the property and declared it a hazard in 1974. Locals took anything of value from inside, removing marble columns from the veranda and filling the concrete foundation with earth and rubble. Firefighters burned the mansion down and removed most remnants of what it once was.

Today, the location of the former St. Croix Valley Country Club is open to the public within the boundaries of Interstate State Park on the Wisconsin side of the river. Ruins of a wading pond, water pumphouse, and limestone gate pillars are still visible on the Silverbrook Loop Trail along an old county highway. Once through the gates, the trail opens into a giant meadow with the remains of bubbling artesian wells and ponds that feed a spring flowing over a waterfall at the bluff’s edge. Upon visiting, it is clear this land has a history—a recorded energy of greatness.

Big Round Lake Retreats, 1952-1977

Maceo A. Finney, the Northern Pacific Railway assistant general chairman of the Dining Car Employees Union Local 516; his wife, Lola; and their son, William Kelso Finney, lived at 437 Rondo Avenue. In 1952, Maceo, an avid fisherman, purchased forty acres from a German farmer named Tolbert Shilling in the heart of recreation and resort country—Big Round Lake, Wisconsin. The lake is in Polk County’s Georgetown Township. Finney partnered with Emmett Searles to buy and parcel the property for other Rondo families to enjoy. It included pasture and ten lakefront lots and was referred to as both the “Finney-Searles Ranch Resort” and “Finney’s Country Place.” The Carter Fletcher and Burt Buckner families joined them.

Life there was enjoyable, and summers spent on Big Round Lake provided a lot of “firsts” for a young William Finney. By age seven, he learned to shoot a BB gun and later became an avid marksman. His father had been raised on a farm and enjoyed country life when he wasn’t working for the railroad. Lola Vassar Finney, a lifelong St. Paulite and owner of Finney’s Beauty Parlor, was less interested in the rugged life. “Mom called everything a rabbit. ‘Get that rabbit!’ she’d say, and I’d have to tell her, ‘No, that’s a chipmunk. No, that’s a mouse.’ ” By age twelve, William learned to drive a car on gravel roads, drive a tractor, row a boat, start a motor, and grow crops.

Trouble at the Lake

Shortly after purchasing the farm and house and building two cabins on the property, the four families were victims of arson in late 1952 and early 1953 after they had closed their homes for the winter.

The Fletcher cabin was the first to burn on December 17, 1952. The Polk County Sheriff’s Department investigated the fire and blamed faulty wiring. Because of this, they ordered electricity to all other structures on the property cut. However, more fires were discovered on January 4, 1953. Flames destroyed the Buckner’s cabin and the Finney/Searles farmhouse. This time, it was clear the fires were targeted and deliberately set. The sheriff’s department discovered two sets of footprints in the snow leading to the structures and the imprints of a gasoline can and crankcase oil container where two people set it down to climb a fence. Police believed the fires were set in the early morning of January 2 and burned for two days before locals reported them. During that time, approximately an inch of snow fell, obstructing other possible clues and evidence.

Rupert Fisk, a real estate and insurance agent from St. Croix Falls, had sold the Shilling Farm to Finney and Searles. Fisk told reporters from the St. Paul Recorder that there was indignation from locals because the families were Black and owned such desirable lakefront property. Fisk also said the most “resentment came from the tavern in a village named Twin Town that is about a mile and a half from the property” at the intersection of County Highways E and G. Fisk said he had to return the money on a lakefront lot he’d sold after the purchaser had been told a “deliberate falsehood” while visiting the tavern. When interviewed by law enforcement, the tavern owner placed blame on the residents of the nearby St. Croix Chippewa Reservation and shared hateful opinions that “[N]egroes were not welcome.”

Fisk notified the families of the first fire on December 19, 1952. Shortly after, Buckner, whose cabin had not burned, received a letter from Integrity Insurance Company postmarked December 19 informing him that his property insurance policy was canceled. By January 10, the Finney and Searles families received notices that their policies also were canceled after they’d just increased them following the Fletcher fire. They were never given a reason for the cancelation. However, Fisk, who had sold the policies to Finney and Searles, said it was too risky to continue insuring the properties unless there was “a change of circumstances [ownership].” Fisk also said he did not think any insurance agency would insure “Negros in that area.” Finney and Searles were resolute. Whether or not they were insured, they would rebuild. The families, with the exception of the Fletchers, constructed cabins in the spring using steel Quonset-hut structures developed during World War II. The Fletchers decided to rebuild on the Apple River near Amery.

Multiple officials and agencies investigated the fires, including Polk County Sheriff James Moore, Wisconsin Atty. Gen. Vernon Thomson, Deputy State Fire Marshal William Rohn, branches of the Wisconsin and Minnesota NAACP, the Wisconsin Commission on Human Rights, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Rev. Carty, as president of the Minnesota Conference of the NAACP, worked directly with the Commission on Human Rights to spotlight this investigation and increase public awareness. Carty called the fires “acts of terrorism that cannot be tolerated by any civilized people.” The fire marshal assured the newspapers that [we] “are not going to tolerate this sort of thing, even though it may happen in other states . . . we’re going to try even harder in this instance to find the guilty persons.”

Reporters from the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder interviewed Big Round Lake community residents after the fires. “It was their opinion that those they talked with seemed ashamed,” and the fires were cowardly. Many worried it might happen again.

William Finney, today a retired St. Paul police chief and recently retired Ramsey County undersheriff, remembers:

“Reportedly, the fires were the work of or at the instigation of the KKK leader in the area. He owned a bar down the road from our cabins. At some point during the investigation, his bar mysteriously burned down and was completely destroyed.”

Newspaper accounts support Finney’s memory. On August 21, a fire did indeed destroy the Twin Town Tavern. The blaze started in the garage at 9:30 am and burned so quickly that by the time the nearest fire department arrived, the structure was consumed in flames. Within forty-five minutes, nothing remained of the business or the attached apartment. It was estimated that the damage caused by the fire was about $75,000. The tavern was never rebuilt. No one was ever prosecuted for the crimes.

While there is not a definite connection between the Twin Town Tavern to the arsons or the Ku Klux Klan, we can piece together the context in which racist attitudes existed in the St. Croix River Valley at the time.

The extremely secretive brotherhood came to the valley in 1924, quickly building membership through Pierce, St. Croix, Polk, and Barron counties. During the 1920s, the KKK was more popular in the North than in the South. Some northern whites were threatened by the growing prosperity of Black Americans moving in from the South. In fact, the Klan argued publicly that “they would be African Americans’ greatest protector provided they stayed within their social position.” Clear Lake, also located in Polk County and only twenty-five minutes from the Finney and Searles property, was an active recruitment area. The Clear Lake Star’s weekly newspaper even included a column called “Klan Komment Korner.” The newspaper’s editor was a known member. By the 1930s, after multiple members were exposed and organizational tell-alls were published, the KKK dispersed but took their beliefs and values to other civic groups, business organizations, and political parties. For example, Fred R. Zimmerman, Wisconsin’s secretary of state at the time of the arsons on Big Round Lake, had, at one time, been a member.

It wasn’t long before officials lost focus on the investigation. In the 1953 Governor’s Commission on Human Rights Annual Report of the Director on Cases of Alleged Discrimination, Director Rebecca Chalmers Barton wrote that her role in investigating the case was to “keep in sympathetic contact” with those involved and also to remind them that “no premature conclusions could be fairly held as to the attitudes of the community. . . .” While there was definite evidence collected by local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies that the fires were deliberate, Barton suggested, “segments of the Negro press played up the incident and jumped to conclusions.” The commission stopped actively working on the case that April after the sheriff said any further involvement would “confuse the issue and possibly detract from the work of the law enforcement officer.”

Even Atty. Gen. Thomson, who spoke at the Wisconsin State Conference of the NAACP in October 1953, did not mention the arsons despite overseeing the lead state agency investigating the crimes. Thomson became governor of Wisconsin in 1957.

Still, this bleak reality of racism came secondary to the joy experienced and the memorable times the Finney, Searles, Buckner, and Fletcher families spent together at their homes away from home.

Leisure at the Lake

Truly, the resort property’s significance is much larger than the arsons. The lake was the site of annual picnics, fishing outings, and Labor Day parties for the Lucky 13, Credjafawn, Breakfast Pinochle, and the Twin Cities Untouchables clubs, and, in the case of the 1957 Credjafawn Annual Picnic, residents from the nearby St. Croix Chippewa Reservation were invited to join in the festivities.

Mr. and Mrs. Alex T. Perry and Mr. and Mrs. William Jones built cabins on the property after the fires, as well. The Jones family fittingly referred to their cabin as “The Knew.” After rebuilding, many Rondo residents and their guests enjoyed the time at Big Round Lake for summers to come.

William Finney and his mother sold their portion of the land in 1977 after Maceo passed away. Finney’s demanding career with the St. Paul Police Department, community commitments, and the upkeep and maintenance required for the summer home ultimately influenced the decision to sell.

A Summertime Reflection

There is so much hope after a long winter. We are eager to plan and envision three months full of outdoor recreation and relaxation. It’s a time of release and refreshment—airing out tents and opening cabin windows. Even local roadside attractions like the Baker Land and Title Company Museum open for the season. The world thaws, and we’re free to roam and enjoy the natural beauty that the Upper Midwest has to offer.

But we must remember the past. These select narratives honor the indomitable spirit of families and communities who have persevered, contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of local history, and affirm the ongoing fight for justice, equality, and the empowerment of all people.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to the Swain family for their friendship and warmth. Without your support, I could not have honored Anna Belle Rideaux’s legacy. And to Cherrelle Swain, I am so lucky to have made a lifelong friend. Additional thanks to William Finney, Readus Fletcher Jr., Mary K. Boyd, Dr. Michael D. Jacobs, Paul Nelson, and the University of Wisconsin-River Falls Archives and Research Center staff for their time, input, and willingness to share with me throughout this project.

Haley Prochnow is president of the St. Croix Falls Historical Society in St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin. A former resident of St. Paul, Prochnow first connected with the history of Rondo as a student at Hamline University. She developed a passion for social justice, research, writing, and public history through her education there. Prochnow also holds a master’s degree from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Her writing celebrates the unique intersection of local culture and social equity and, often, ephemeral feminist histories.

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 3, Summer 2024

- Creators

- Haley Prochnow

- Topics