St. Paul’s Forgotten Radio Pioneer Maurice G. Goldberg

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 1, Winter 2025

- Creators

- Rebecca E. Bender

- Topics

Catching Waves: St. Paul’s Forgotten Radio Pioneer Maurice G. Goldberg

By Rebecca E. Bender

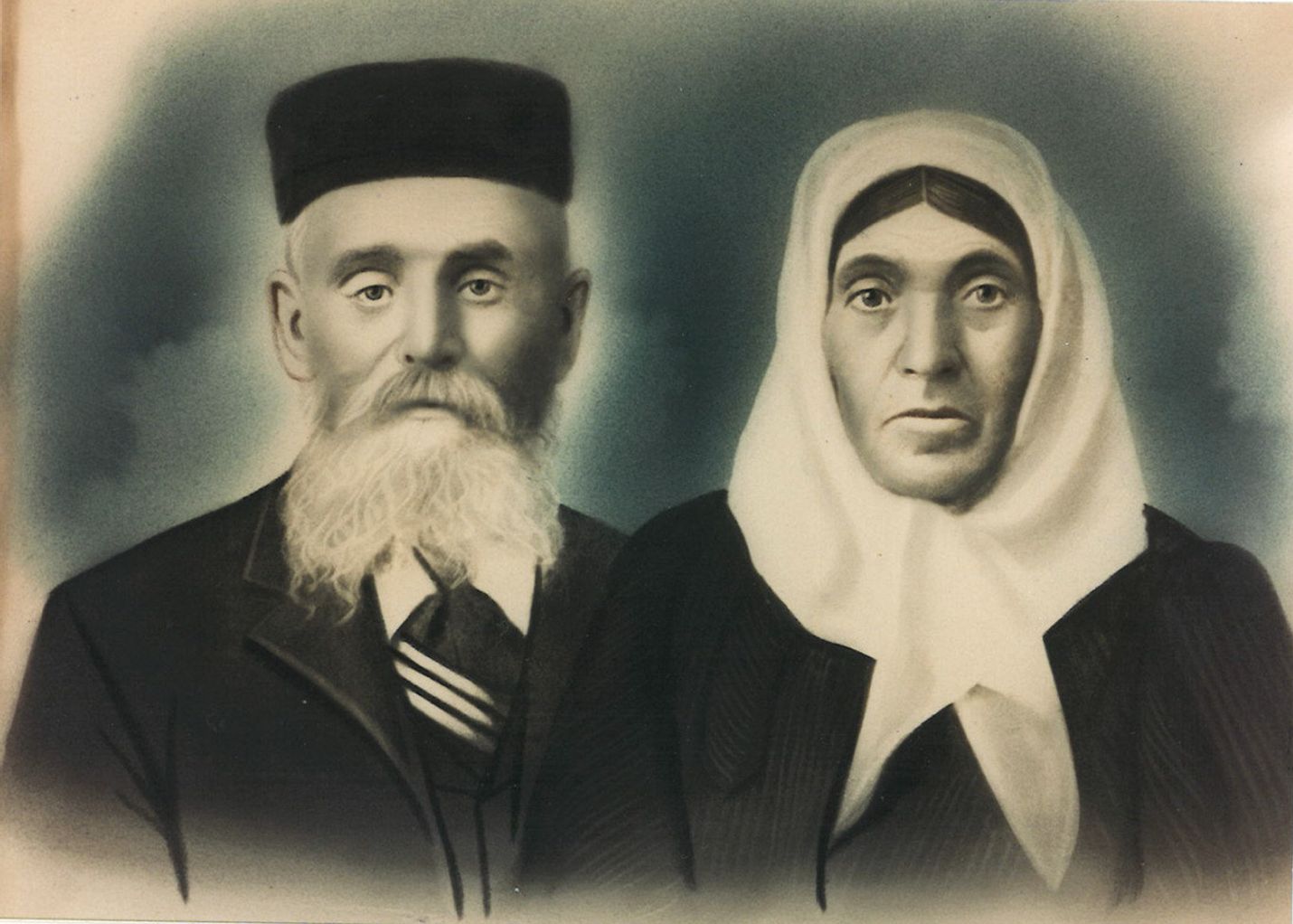

From the Dnieper to the Straight River

To understand how the Abraham Burch family ended up in Minnesota—which led to son Maurice Goldberg’s wide-ranging contributions to St. Paul’s fledgling radio industry in the first half of the twentieth century—one must start in the small town of Yompila in the Russian Pale of Settlement.1 For there, beginning in around 1860, at the half-way point between Kiev to the north and Odessa 250 miles to the southeast, near the Dnieper River, sat a crossroads inn. It was run by Joseph and Lillian (Leah) Burch. Leah was an amputee after a bad fall, which, to those who knew her, seemed to have no effect on her drive to make the family inn a success. Travelers in horse-drawn vehicles stayed the night at the inn, where they were offered food and drink, while their horses stabled in a dirt-floor barn. “Though liquors of a rough character were sold, the popular drink was tea, served from a large samovar, in which hot water was kept day and night.”2

Abraham Burch, born in 1870 and known as A.B., was the third oldest of the five boys and two girls born to Joseph and Leah. A.B. left home at the age of thirteen to help support the family, performing swamper services at a saloon in Odessa, i.e., janitorial work (including cleaning the floor and spittoons), bartending, and other odd jobs. At eighteen, during the time of Czar Alexander III, A.B was inducted into the Imperial Russian Army, where he served about four years, before, atypically, being allowed to leave prior to the usual twenty-five-year servitude. As pogroms and mistreatment of Jews were a way of life in Russia, large numbers of Jews attempted to leave.

At twenty-three, A.B. was the first of his family to arrive in America, landing in Boston, where he worked first as a pants presser for $2 a week and, later, as a tailor. As he spoke no English upon arrival, he taught himself—learning largely from a combination English and Yiddish children’s schoolbook. After scrimping and saving for a few years, A.B. sent for his parents and the rest of the family.

As a young man, A.B. also took it upon himself to change the family name. Contrary to the common trend among many immigrants who sought to “Americanize” their names, A.B. chose the opposite path. He wanted to ensure that other Jews in his new home would know he was Jewish, and wanted a name that would help him connect with those of his faith. That is how A.B. Burch became A.B. Goldberg.

After his business partner stole from their joint assets, A.B. moved to the Midwest, settling in Owatonna, Minnesota, on the Straight River—about 5,000 miles from the Dnieper River. There, he started over as a peddler, first carrying his wares on his back, and then working out a deal with a man who owned a horse and wagon, to drive him from place to place.

Once A.B. purchased his own rig, he proposed marriage to 5-foot, blue-eyed, brown-haired Sarah Schwartz. Sarah’s path to Minnesota was akin to A.B.’s, though her early years in Russia were not quite as difficult as his had been. She lived in the southern Pale of Settlement in Lepkan, close to modern-day Moldova and Romania. Her mother owned a natural dye business (from plants). Her father was a contractor of small houses, and her grandfather owned and operated a successful leather store. After immigrating to America by way of Germany, Sarah worked first in a Minnesota candy factory—then a cigar factory—before marrying A.B. in 1898 and moving to 127 Rose Street in Owatonna. A.B.’s occupation in the 1900 Census is listed as “buying and selling iron” (scrap dealer).3

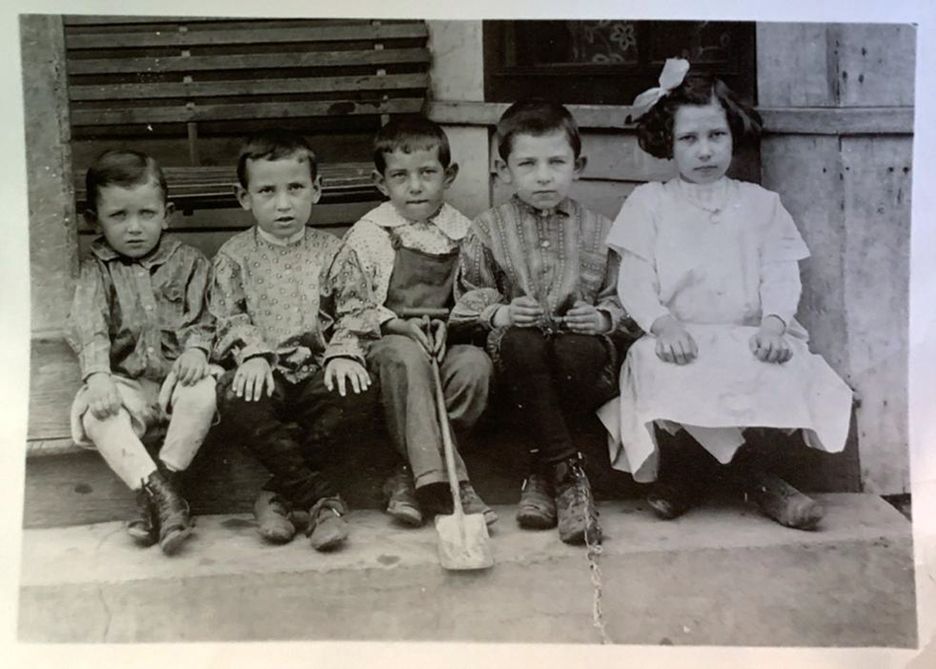

Four of the Goldberg children were born in Owatonna. The oldest child was my mother’s mother, Minnie, born in 1900. One year later, Maurice was born. Then A.B. decided the family should move to St. Paul, which offered more opportunities to encounter Jewish culture, religion, and education.

The West Side Flats Years

The Goldbergs’ first home in St. Paul was at 239 East Fairfield, in the West Side Flats. In this area, bound by the Mississippi River on the north and the bluffs to the south, lived French-Canadian, Irish, German, Jewish, Russian, Polish, Syrian, Lebanese, and later, Hispanic communities in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century. The cultures of these coexisting groups thrived for decades in this densely populated space despite the Passover/Easter spring-flooding of the mighty Mississippi.4

The Flats were situated directly across the river from downtown St. Paul and southeast about one and a half miles from the elegant Summit Avenue mansions. A.B.’s occupation in the 1910 census was listed as a “wholesale merchant” in the “junk industry.”5 In other words, the scrap dealer was still making deals to purchase items discarded or found to be useless to their original owners. In a big lot behind the Goldberg house, which he called “the shop,” A.B.—“Pa” to his children—conducted his scrap iron business. His children saw firsthand how “one man’s trash, [could become] another man’s treasure.”6

Next to their house, A.B. constructed a building with a retail store on the main floor and living quarters upstairs. After unsuccessfully trying “mercantiling,” he rented out the space for a boxing gym, a candy store, a barber shop, and then to tenant Aaron Stacker. This “portly and genial man,”7 owned a combination grocery store and delicatessen called Levooneh’s, where Jewish fare like matzos, pickled herring, and corned beef could be purchased, as well as Hebrew books.

The loft in a large woodshed attached to the back of their home housed pigeons. Occasionally the family had squab for dinner. To make their own fun, the Goldberg kids put on shows in this same woodshed. Oldest son Maurice wrote the plays, and the rest of the children would take on the different parts. They charged safety pins for the admission fee to the woodshed theater performances, except when a young girl whose parents were in vaudeville participated with them. Then they felt justified in charging one penny per customer.

To the Attic and Beyond

In 1915, because of the success of A.B.’s scrap metal business, the Goldbergs, then with six children, were one of the first Jewish families to move out of the West Side Flats and into the city’s Hill District. Maurice was fourteen years old when he left the Flats. His father’s scrap business remained in the Flats for over 45 more years.

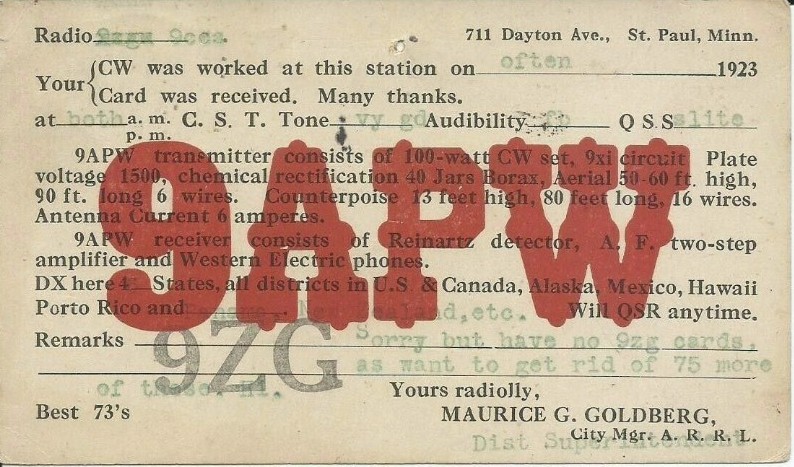

A.B. and Sarah bought a Colonial Revival style home with impressive Tuscan columns between St. Albans and Grotto Streets at 711 Dayton Avenue. The first services at the newly constructed Cathedral of St. Paul (one mile away) were held the same year the Goldbergs moved in. F. Scott Fitzgerald was, around the same time, living seven-tenths of a mile away at 599 Summit Avenue, working on his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920).

After a respectable length of courtship, in January of 1923, my grandmother Minnie Goldberg married Samuel A. Gordon, eldest son of Rabbi Jacob Gordon from Minneapolis. Maurice, her brother, was one of the ushers at the wedding.

Three years earlier, in October 1920 when Maurice was 18, he had been licensed by the United States Commerce Department as an amateur radio operator.8 In March 1923, Maurice graduated from the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering and as a second lieutenant in the Signal Corps. As of April 1, 1924, the Radio Service Bulletin official listing of radio stations in the US reported that a radio station was being operated in St. Paul [by Maurice Goldberg, d/b/a Beacon Radio Service].9

Maurice selected the call letters “KFOY,” which stood for “Kind Friends of Yours.” KFOY had its first official broadcast in March 1924.10 With Maurice’s early work in radio, helping others deal with the unexpected challenges of the industry, these call letters became his self-fulfilling prophecy. The location for his first broadcasts was, like Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi before him, in the attic of the family home. Maurice was not only the operator and announcer for the station, he also was “the genius who tinkered Saint Paul’s first commercial radio station into existence—using home-made parts instead of purchased equipment and guts instead of money.”11 The KFOY broadcasting station later moved to the Pioneer Building at 373 North Robert Street, where drapes of monks’ cloth eliminated acoustical issues.

On October 7, 1923, at age twenty-one, Maurice (who also went by M.G.), was elected vice-president of the Twin City Radio Club, at its meeting in the mayor’s reception room of the courthouse. The following spring, Maurice was reappointed St. Paul district superintendent of the American Radio Relay League (ARRL), the national association for amateur radio.

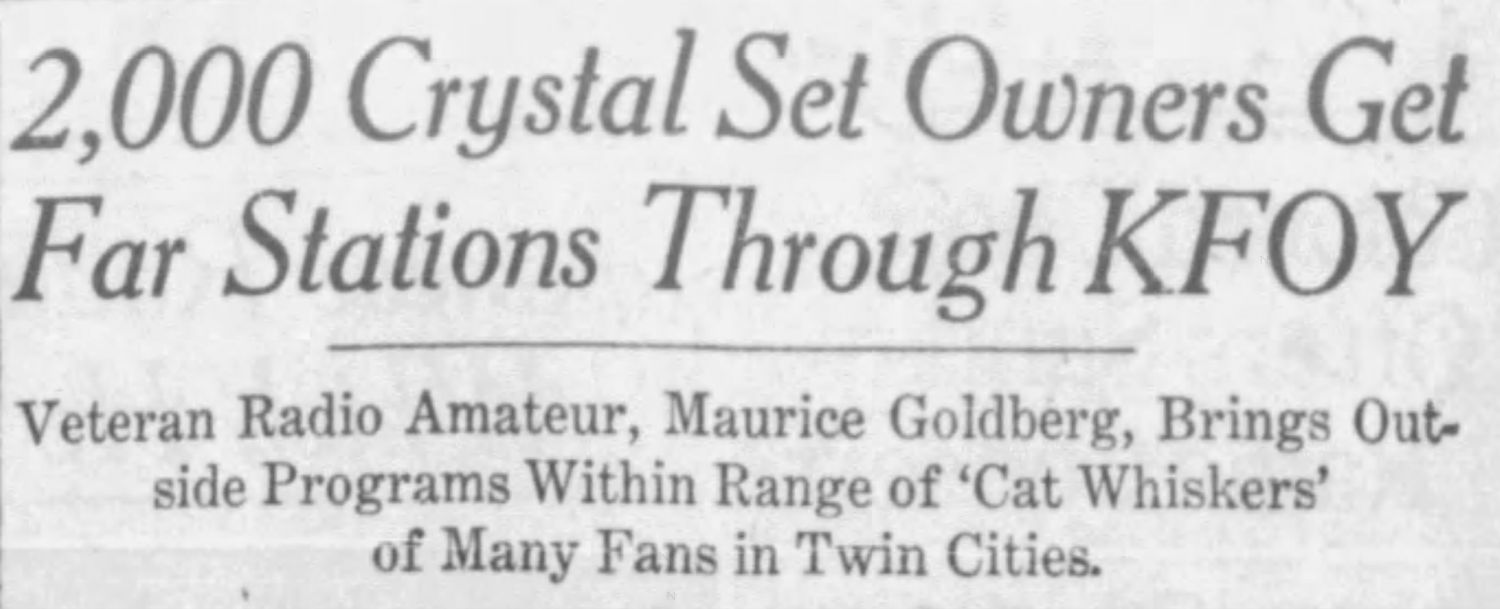

The 1920s was a time when crystal sets or “cat’s whiskers” were the new thing in receiving radio signals. No battery or electricity was needed, as the crystal detector obtained its power from an external wire antenna. An article in the Minneapolis Star noted the far-reaching impact which a certain “radio pioneer” had in the Twin Cities at the time:

Two thousand crystal set listeners in the Twin Cities adjust the “cat whiskers” nightly and listen to programs broadcast by KDKA, East Pittsburgh [the world’s first commercially licensed radio station] and other distant stations. . . .

Maurice Goldberg, 711 Dayton Avenue, St. Paul, former University of Minnesota student and a veteran radio amateur, has made all of this possible. Almost nightly you can hear him announce KFOY— “Kind Friends of Yours”—and then the re-broadcasting of distant programs begins. . . .

Friends had telephoned him that they found it impossible to “get outside” the Twin Cities because of the static. Goldberg went to his radio room on the third floor of his home and began tuning with his 8-tube super-hetrodyne. He was able to get several distant stations. . . . He put on the loudspeaker, adjusted a microphone in front of it, and began rebroadcasting through KFOY. The 100-watt broadcast station was able distinctly to re-broadcast the East Pittsburgh program. . . .12

Another article mentioned Maurice’s helpful spirit in addressing another issue:

Twin City Hearkeners should rise en masse and give Maurice Goldberg . . . a vote of thanks for the checkup on reception conditions which he broadcasts over KFOY each evening at 10:05. Listeners who are quick to blame their sets for imperfect reception should first tune in on this station (wave length 252) and obtain Mr. Goldberg’s authoritative report on conditions before complaining to their dealer.13

KFOY also took seriously its responsibility to inform the electorate. In October 1924, only two stations in Minnesota broadcast the speech of well-known Wisconsin Senator Robert M. La Follette at the Kenwood Armory. One was St. Olaf’s college station in Northfield; the other was KFOY, St. Paul (from the home of A.B. and Sarah Goldberg). At the time, “Fighting Bob” La Follette was the third-party candidate for president, on the Progressive ticket. He garnered 16.6 percent of the popular vote, the third highest percentage for a third-party candidate since the Civil War.14

While busy with his broadcasts, Maurice was also continuing to share the results of his experimentation with radio waves and equipment. In April 1924, an article written by Maurice was published in QST, the official magazine of the American Radio Relay League. In this article, Maurice was educating others regarding his most successful attempts to limit man-made interference with radio signals.15

Then, on March 3, 1927, Maurice used his engineering talents to perform a breakthrough successful test communication:

M. G. Goldberg, engineer of radio station KFOY, St. Paul, and a pilot of the Northwest Airways, Inc. circled the Twin Cities in a radius of 40 miles and heard music, weather reports [from a government meteorologist] and addresses [including by St. Paul Mayor L.C. Hodgson] broadcast by KFOY for two hours. Weather reports were heard through earphones by the men flying 1,500 feet in the air.16

This first step led to the installation of voice communication systems in airplanes. Prior to this successful experiment, pilots depended on dot and dash code message systems for weather reports and conditions of flying fields.

Back on the ground, loyal KFOY listeners welcomed the station’s customary offerings. According to radio listings in the Minneapolis Journal, in 1927, KFOY’s typical broadcasts in the evening ranged from classical music performances to financial reports, the “Old Time Dance Orchestra,” and the all-important “Reception Reports.”17

The Merger

In addition to founding, financing, and operating KFOY, Maurice was also “technical operator” for WAMD in Minneapolis (Where All Minneapolis Dances). WAMD started broadcasting on February 22, 1925, almost one year after KFOY’s first broadcast. WAMD operated out of a studio on Grant Street and Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis and also broadcast from the Marigold Gardens dancehall. Five months later, WAMD moved its studios to the Minneapolis Radisson. WAMD’s founder was Red Wing native Stanley E. Hubbard.18

In late 1927, one unexpected event and one “kind” deed set the stage for the imminent end of KFOY. In November 1927, WAMD’s transmitter was destroyed by fire, which took the station off the air. Two weeks later, an article in the Minneapolis Journal noted that WAMD would be back on the air, thanks to WAMD’s using the 250-watt KFOY transmitter.19

The story, as told by Hubbard Broadcasting on its website, goes that “by consolidating and trading in WAMD’s license and the license of another local station, a new Twin Cities station was born in Saint Paul.” Four months after the fire, “On March 29, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge pressed a gold telegraph key from the White House to officially activate KSTP-AM radio’s antenna.”20

It was not just “another local station” which was consolidated with WAMD to become KSTP. It was KFOY, the first commercial radio station in St. Paul. The story that had been handed down in our family was that my Great Uncle Maurice liked the thrill of innovation, inventing, and problem-solving to help people, but didn’t have much interest in accumulating wealth.21 It was believed that Maurice sold his license and all his equipment to Mr. Hubbard, for a much smaller sum of money than it was worth, when Hubbard formed KSTP, and then Maurice moved on to new frontiers. It was recently learned that this story was only partially correct.

Corrective History

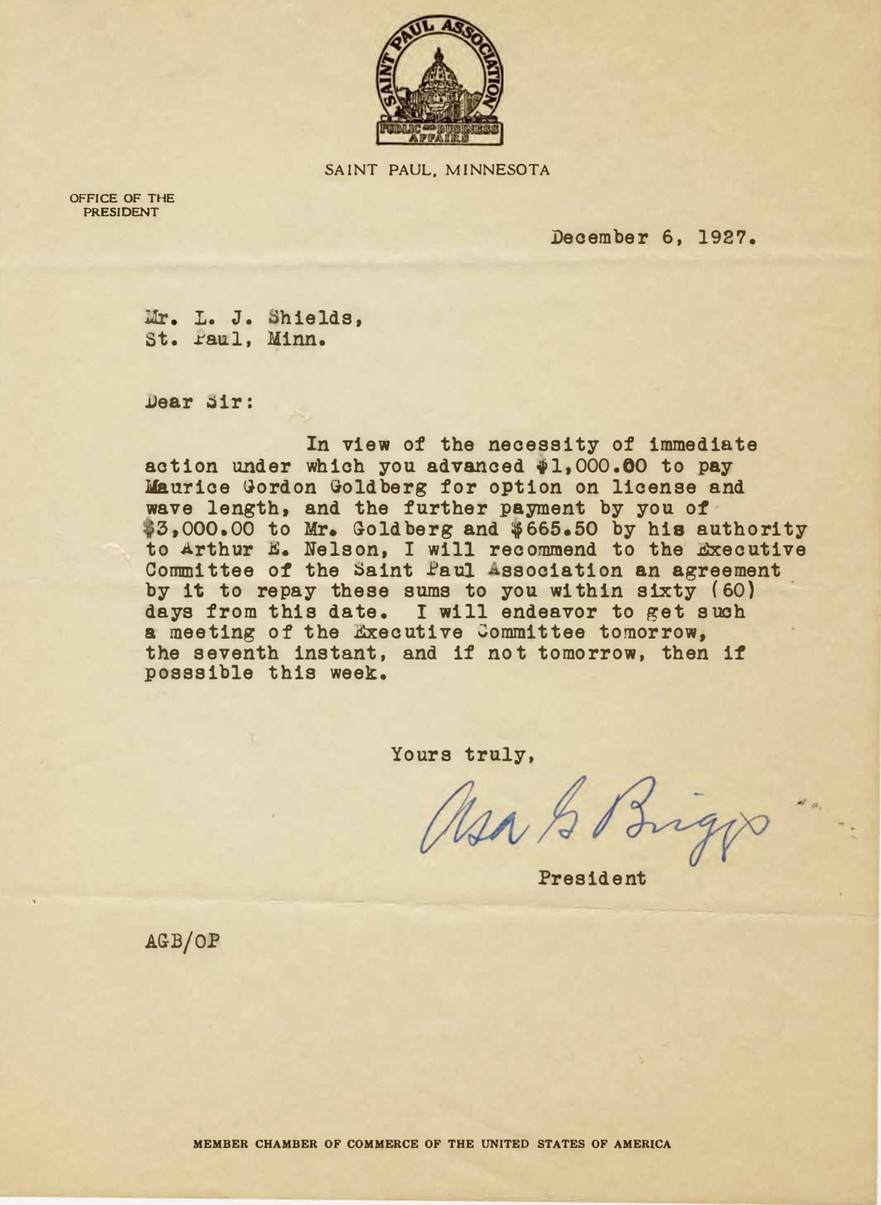

The actual details of this transaction and how it came about were recently rediscovered, almost one hundred years after the events in question, thanks to Hubbard Broadcasting, Inc. archivist Glenn D. Griffin. In responding to an email inquiry, Griffin kindly combed through the archived files.

Interestingly, the deal to combine KFOY and WAMD to form KSTP does not appear to have been negotiated at all by Mr. Hubbard, as has been assumed by many. Though various sources still refer to Stanley E. Hubbard as having “bought” or “founded” KSTP radio,22 Hubbard’s name is not mentioned in the unearthed original documents concerning the station’s formation. A Minneapolis Journal article looking back at the merger stated that for four years, “Hubbard struggled on with his little station [WAMD],”23 then WAMD’s old transmitter burned down. A few months earlier, Hubbard became associated with Lytton J. Shields, president of National Battery Company of St. Paul.24

The contemporaneous documents located by Griffin fill in the rest of the picture. It was Shields, an influential Twin Cities dealmaker and president of the Radisson Radio Corporation and National Battery Company—who until now has been largely overlooked in the history of St. Paul Radio—who got the ball rolling. Shields made a proposal to St. Paul’s “Association of Public and Business Affairs” (Chamber of Commerce) to construct and put in operation a new radio station, with headquarters exclusively in St. Paul, to provide “first class service,” including not less than one hour per day of “New York remote control service, if this can be obtained.”

In return, a contract was signed between representatives of the St. Paul Chamber and Mr. Shields, with the following three significant provisions:

- The St. Paul Chamber would transfer KFOY and its equipment to Shields’ National Battery Company;

- The St. Paul Chamber would lend the National Battery Company $30,000, which was to be paid back within three years of the first date of broadcast by the new St. Paul station; and

- Mr. Shields’ company would pay what the St. Paul Chamber had agreed with Maurice Goldberg to pay for the purchase of KFOY, i.e., $4665.50 [$4000 to Maurice and $665.50 to be paid at Maurice’s instruction to Arthur E. Nelson, then Mayor of St. Paul].

On June 1, 1928, approximately six months after fire destroyed WAMD’s transmitter and the license and equipment of KFOY were purchased, Shields reported to the St. Paul Chamber that the value of the equipment for the station (according to the American Appraisal Company) was $219,000. It can be reasonably assumed that the great majority of that equipment came from the KFOY acquisition. The conversion of the equipment value ($219,000) to present-day dollars amounts to approximately $3 million, though obviously the equipment, which was innovative in 1928, would now be outdated. With this information, and knowing that Maurice received $4,000, the belief that Maurice did not receive nearly the value of KFOY in the deal to form KSTP appears to have been confirmed.

By December 31, 1929, a year and nine months after the first KSTP broadcast, $17,500 had been paid back on the $30,000 loan from the St. Paul Chamber to the National Battery Company. However, as the previous year had resulted in KSTP experiencing net operating losses of $20,000, Mr. Shields wanted to negotiate a new proposal. He advised the Chamber that in light of this loss, and though there was no way to estimate what additional funds may be needed to secure a better wavelength or other obligations, he would agree to assume any unknown, large future expenditures for KSTP, in return for some concessions.

The St. Paul Chamber agreed to forgive the remainder that Shields’s company owed on the loan ($12,500), as well as agreeing that St. Paul was no longer required to be the exclusive city mentioned in KSTP’s station announcement (as long as St. Paul was still mentioned, Minneapolis could also be mentioned), and to allow the KSTP studio to be located outside of St. Paul’s city limits.25

Stanley E. Hubbard was the KSTP Manager and vice-president of National Battery Broadcasting Company, KSTP’s licensee, until 1935. Shields passed away that year.26 Hubbard then became the company’s president, replacing Shields.27

If We Can’t Fix It

A December 1944 article in Radio and Television Retailing magazine provides insights as to some of Maurice Goldberg’s activities and interests after the KFOY years, while raising children David and Sylvia with his wife Isabel.28 Maurice was continuing with a desire he likely inherited from his father to find uses for items others discarded, as well as with his quest to help others with his discoveries. The article highlighted Maurice’s radio and television repair shop, Beacon Radio Service Shop, which had been in business at 142 East Fourth Street, St. Paul for the previous twenty years. Each day he would come into work, Maurice passed by the sign he had placed outside his store: “If We Can’t Fix It, Throw It Away.” M.G. Goldberg took that slogan to heart, finding creative ways to keep radios running.

When parts to repair radios started to become scarce, Maurice began experimenting again. He found he could interchange tubes by rewiring sockets. His conversion circuits allowed him to use tubes that were available, though they were not designed for certain radios. Piles and piles of mail were delivered to M.G. Goldberg, as radio dealers and servicemen sought to learn his new techniques. And by 1955, Maurice proved he was no one-trick-pony, publishing articles regarding troubleshooting issues encountered in television repairs.29

Epilogue

I remember Maurice in the 1960s as the tall, soft-spoken uncle in a one-piece work jumpsuit, with the knot of his tie and white dress shirt visible underneath. He drove from St. Paul to St. Louis Park, a Minneapolis suburb, so he could repair our black and white TV in the blond wood console in our den. He always had the tubes we needed and quietly worked with a smile, so I could watch “Lunch with Casey” and, several years later, “The Flying Nun.” My mom wouldn’t have considered calling anyone else to repair our TV, as that would have been a betrayal of sorts for both her and her uncle.

About forty years after Uncle Maurice’s sale of KFOY’s license, my mom, sister, and I were waiting near the downtown Minneapolis Radisson for my dad to meet us after he finished work at his North Minneapolis store. We would then typically eat dinner together at the Café DiNapoli, the Nankin, the Forum, or La Casa Coronado, and then would go to a movie. A gentleman in a suit was also waiting for someone at the hotel. While waiting, he introduced himself to my mom.

“My name is Stanley Hubbard,” he said.

My mom introduced herself and explained to the younger Mr. Hubbard—whose father, Stanley E. Hubbard, was the man whose station WAMD merged with KFOY to form KSTP—that her uncle was Maurice Goldberg. Mr. Hubbard shook my mom’s hand warmly and said simply, “Maurie is a genius.” Then my dad’s white Buick LeSabre appeared. We wished each other a good evening and went our separate ways.

The last time I saw my Uncle Maurice was at a small family get-together for my eighteenth birthday in 1976, at my grandparents’ home at 1696 Watson Avenue in St. Paul. My Baba Minnie’s birthday and mine were two days apart, so my parents and sister Nancy brought a joint cake for the two of us. As we were about to sit down for our treat, Minnie suggested that we wait a minute so she could invite Maurice to stop over for cake and coffee.

Uncle Maurice seemed to arrive instantly. The warm hugs, smiles, laughter, and the cheery, hot pink frosting flowers resting on buttercream waves over moist chocolate cake couldn’t remove the sadness in the dining room. Both my Baba and Uncle, though they never smoked a cigarette in their lives, had been diagnosed with lung cancer. Maurice passed away in 1977. Minnie died a year later. Each of them, in their own way, made St. Paul and beyond a better place.30

Perhaps the author of the Pioneer Building Newsletter from February 1949 said it best, in describing a conversation with Maurice Goldberg:

“What you ought to do, Morry [sic],” we declared, “is put on a salesman and punch up your television sales.”

“No point in it,” he shrugged, “as it is, I have to work half the night installing the sets people come in and buy.”

No, Morry doesn’t run his shop for people who like to be sold—he runs it for those who are willing to seek out quality in men and in merchandise.

Acknowledgments

I send a thank you heavenward to my grandmother Minnie Goldberg Gordon, my Great-Uncle Hy Goldberg, and my mother Frima Gordon Bender, for taking the time to share the family history which enabled me to write this article. Also, without Pavek Museum’s Collections Manager Kallie Zieman, Tom Gavaras at RadioTapes.com, Hubbard Broadcasting’s archivist Glenn D. Griffin, architectural historian Richard L. Kronick, my late aunt Josephine Berg Simes, and Maurice Goldberg’s grandson Randy Pentel, the stories told herein would not have been complete. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my family, who support my desire to preserve history, including Lincoln, Nancy, Barry, Marshall, Malcolm, Sage, Jackson, Abby, and Steven, and to Ramsey County History editors Meredith Cummings and Andrea Swensson and the Ramsey County Historical Society for assisting me in my pursuit. It is my honor to tell a small part of Maurice Goldberg’s inspiring story—one of a lifetime of curiosity and selfless generosity. I thank him and like to believe that he, a modest man, approves of this piece. Shortly after reconnecting with Maurice’s grandson Randy, who shared with me an amusing anecdote about Maurice and a feisty cardinal in St. Paul, a vibrant, red male cardinal landed on a desert shrub close to me, while I was walking in southcentral Arizona. I have since learned that cardinal sightings in that area are rare.

Minnesota-born and raised Rebecca E. Bender practiced law in Minnesota for 18 years prior to beginning her second chapter as a mom, teacher, speaker, and author. The excerpts and photos in “Catching Waves” are from Rebecca’s recently completed manuscript, Deep Footprints in the Snow: A Minnesota Memoir. Her first memoir/biography, co-authored with her dad Kenneth Bender, Still (North Dakota State University Press, 2019 hardcover, 2022 paperback), won the Midwest Book Award Gold Medal, the First Place Independent Press Award and an Independent Publishers’ Award. Rebecca’s prose and poetry have been published in various online and print journals. She has also given book talks at events sponsored by a wide range of historical societies and libraries.

NOTES

- By czars’ edicts, almost all Jews, from the late 1700s through the early 1900s, were restricted to living in and working in a designated area in the western part of the Russian Empire. Approximately 94 percent of the total Jewish population of Russia lived in “the Pale” in the late 1800s. Klier, John, “Pale of Settlement,” YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2010, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Pale_of_Settlement.

- Some of the tales of the Goldberg family herein, including this quote, are from Goldberg, Hy, “History of A.B. Goldberg and Sarah Goldberg,” circa 1975. Other stories were told to the author for decades by her grandmother, Minnie Goldberg Gordon and her mother, Frima Gordon Bender, or recently learned from her cousin, Randy Pentel.

- 1900 U.S. Census, Steele County, MN, Population Schedule 1, Owatonna, Ward 3, handwritten, Number 3.

- Rosenblum, Gene H., The Lost Jewish Community of the West Side Flats, 1882-1962 (Arcadia Publishing, 2002); Nelson, Paul, “West Side Flats, St. Paul,” MNopedia, March 30, 2015, https://www.mnopedia.org/place/west-side-flats-st-paul. On August 9, 1960, Resolution No. 123 of the St. Paul Port Authority declared the West Side Flats an Industrial Development District. Resolution No. 193 on November 20, 1962, approved acquisition of the property. In all, 2,147 individuals and numerous businesses were expelled. Port Authority of the City of Saint Paul Records Collection, Minnesota Historical Society; Don Boxmeyer, A Knack for Knowing Things (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003); Coleman, Patrick, “A Nostalgic Zephyr: William Hoffman on the Old Jewish West Side,” Saint Paul Almanac, January 31, 2012, https://saintpaulalmanac.org/2012/01/31/a-nostalgic-zephyr-william-hoffman-on-the-old-jewish-west-side.

- 1910 U.S Census, Ramsey County, MN, Population Schedule, St. Paul, Ward 6, handwritten.

- Goldberg, Hy, “History of A.B. Goldberg and Sarah Goldberg” (circa 1975). This quote, which has morphed into the creed for scrap dealers and antiques sellers, has been traced to the introduction written by Hector Urquhart, to Popular Tales of the West Highlands, (Campbell, J.F., Edmonston and Douglas, 1860).

- Hoffman, William, Those Were The Days, T.S. Denison and Company, 1957.

- Pavek Museum of Broadcasting Newsletter, Vol. 2, No. 2, April 1991, St. Louis Park, Minnesota. About two years prior to this licensing, Maurice’s knowledge of radio operations led to his being invited to operate the radio lifelines on an expedition to the North Pole. Maurice, age 16, declined. Author’s November 9, 2024, conversation with Randy Pentel.

- “Radio Service Bulletin, No. 84,” Department of Commerce, April 1, 1924.

- Ingersoll, Charles, Minnesota Airwaves, 1912 through 1939 and Radio Trivia, “KFOY—Kind Friends of Yours, the Beacon Radio Service, St. Paul, Minnesota.”

- “KFOY,” Around the Corridors, Pioneer Building newsletter, February 1949, published by Davidson Owner-Managed Properties.

- “2000 Crystal Set Owners get Far Stations Through KFOY—Radio Amateur Maurice Goldberg, Brings Outside Programs Within Range of ‘Cat Whiskers’ of Many Fans in Twin Cities,” Minneapolis Star, May 11, 1924. Shortly thereafter, an avalanche of postcards and letters from strangers arrived at the Goldberg home on Dayton, causing Maurice to realize that he was onto something. There was a strong demand for rebroadcasting of distant programs. Maurice listened to his listeners and continued these broadcasts.

- The List’ning Post column by the “Night Watchman,” Minneapolis Star, February 24, 1926.

- Dreier, Peter, “La Follette’s Wisconsin Idea,” Dissent Magazine, April 11, 2011, also refers to Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson as one of La Follette’s “political offspring.” Shideler, James H. “The La Follette Progressive Party Campaign of 1924,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, 33(4):444-457, June 1950. Though La Follette died in 1925, Harold Ickes, Sr., a senior advisor to La Follett on his 1924 campaign, later was a key adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt for his New Deal in the 1930s.

- QST, Volume VI, No. 9, p. 14, April 1923, M.G. Goldberg, “A Study of Filter Systems for Transmitter Tube Plate Supply;” QST, Volume VII, No. 9, p. 11, Maurice G. Goldberg, “Loose-Coupled Transmitting Circuits,” April 1924. The magazine also noted that a well-respected MIT Professor had relied upon Maurice’s previous experiments.

- “Messages are Sent Flyers by Radio,” Minneapolis Star, March 3, 1927.

- “Radio Programs for the Week,” Minneapolis Journal, May 14, 1927, August 27, 1927, October 1, 1927.

- Ingersoll, Id.

- “Three Stations Here Get New Waves,” Minneapolis Journal, November 26, 1927.

- “A History of Firsts,” Hubbard Broadcasting, https://hubbardbroadcasting.com/our-company/history/.

- This recollection by the author was confirmed in a November 9, 2024, conversation with Randy Pentel, one of Maurice Goldberg’s grandsons.

- The website of Pavek Museum of Broadcasting’s Hall of Fame provides, in part, “He [Stanley E. Hubbard] founded KSTP . . . in 1928.” Minnesota Aviation’s Hall of Fame website refers to Mr. Hubbard “buying station KSTP.” Of course, correcting these inaccurate statements concerning KSTP’s origins does not lessen the numerous subsequent achievements in radio and television by either Stanley E. Hubbard, Stanley S. Hubbard, or Hubbard Broadcasting.

- “How Men and Machinery Built KSTP Broadcasting Leadership,” Minneapolis Journal, August 11, 1935.

- In Ramsey County History, Spring 2009, vol. 44, no. 1, an article titled, “Minnesota Politics and Irish Identity: Five Sons of Erin at the State Capitol,” by John W. Milton, discusses in part Lytton James Shields’ uncle, General James Shields.

- Letters and minutes from Hubbard Broadcasting Archives.

- Lytton James Shields, Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/151054514/lytton-james-shields.

- “Hubbard is named president of KSTP,” Minneapolis Star, November 26, 1936.

- “Conversion Circuit Specialist,” Radio and Television Retailing, December 1944. Another one of Maurice’s interests was birding. Maurice was twice president of the St. Paul Audubon Society. The Goldbergs’ 20-by-50-foot backyard on Palace Avenue in St. Paul was turned into a bird sanctuary, where Maurice and the author’s great-aunt Isabel fed and identified 98 species of birds. Maurice’s banding of birds and careful notations in his spiral notebooks, after the birds landed in the mist net in his backyard, provided much previously unknown information regarding migration patterns. “They Turned a City Lot into Yardful of Song,” D. Cunningham, Minneapolis Tribune, December 29, 1963; author’s conversation with Randy Pentel, November 9, 2024; “Bird Migration To Be Topic of [Ramsey County Garden Club] Meeting,” (presented by M.G. Goldberg), Minneapolis Tribune, March 8, 1970. The author also recalls, after a number of family meals, watching slides of the birds which appeared in her great-uncle and aunt’s yard in St. Paul, with detailed explanations by her uncle.

- M.G. Goldberg, “Troubleshooting Hum in Television Receivers,” Technicians and Circuit Digest,1955.

- In addition to being an active member of the Osman Shrine Women’s Auxiliary, Temple of Aaron Synagogue Sisterhood, Sholom Home Auxiliary, Talmud Torah PTA, and Hadassah, the author’s “Baba” Minnie Goldberg Gordon also served as President of St. Paul Women’s Coordinating Council for Civil Defense, President of Women’s Auxiliary Post 162 Jewish War Veterans (St. Paul), National Vice President of the Jewish War Veterans Auxiliary, Local Chairman for the National Jewish War Veterans Convention, held in St. Paul in 1947, and enthusiastic pianist for all of the above. Despite all her activities, Minnie always seemed to have freshly baked cinnamon, almond kmishbroit (a softer version of biscotti) or mun pletzels (poppyseed cookies) available, and showered her five grandchildren with love and life lessons.

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 1, Winter 2025

- Creators

- Rebecca E. Bender

- Topics