The Everyday Activism of the North Central Voters League in St. Paul

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 4, Fall 2024

- Creators

- Adam Bledsoe

- Topics

By Adam Bledsoe

In 1926, the St. Paul Echo reflected on the necessity for Black activism in Minnesota, arguing that:

[d]isillusionment comes early to those of us . . . who are dusky in hue. Democracy is oftener than not demonocracy; justice seems to have two facets; opportunity, translated to us by white tongues, comes through as lack of opportunity; and even Christian loses much of its meaning.

But we must all learn . . . that we must live with our skins, and that perpetual complaint will do little to help our cause. Forgetting what we are is impossible as long as we are surrounded by a white world, but there is open to all of us that avenue of escape down the hard path of conscientious endeavor in every worth-while pursuit. That is the only simple panacea for the vanquishing of racial obstacles.

Minnesota’s capital city offered insight into the imperative of the Echo’s call. A 1930 study of local businesses found that 80 percent of surveyed firms would not consider hiring Black workers, and many unions had constitutional bans on admitting Black laborers. A majority of Black Twin Citians worked in a few industries—railways, meat processing, hotel and restaurant hospitality, and domestic labor, for example—where they frequently experienced long hours, low pay, and demeaning treatment from their clientele and bosses. In the face of these hard realities, Black communities committed themselves to various paths of “conscientious endeavor.” Mobilizing on numerous fronts, these early twentieth-century Minnesotans helped enact a fair employment ordinance, and later, a law in Minneapolis—one of the first of its kind in the country. Across different industries, local Black-led unions scored several workplace victories, which improved labor conditions. They also took the lead in passing the country’s first statewide fair housing bill in 1961.

Such activism demonstrated Black Minnesotans’ commitment to changing the everyday conditions under which they lived. Nonetheless, the mid-twentieth century saw many residents continuing to live life on the margins of society. Whereas by late 1964, unemployment in the Twin Cities had dropped to around 3 percent and employment reached record proportions in 1965, nearly 17 percent of nonwhite families in the largely Black Selby-Dale (Rondo) neighborhood of St. Paul lived below the poverty line. Community members complained of the city’s public schools’ de facto segregation, while local scholars criticized the “focusing [of] remedial programs on schools in the Negro ghetto.” In 1970, a survey noted that Black St. Paulites lacked representation in the public sector, as agencies rarely employed workers of color, and there were no Black elected officials. This exclusion from St. Paul’s mainstream institutions was not lost on community members. Some residents diagnosed this marginalization as structural, arguing:

Poor people are not poor by their own desire or lack of enthusiasm or lack of initiative. They are poor because of the system that was created by someone else. They are victims of their own society.

As was the case in many US cities, imposed immiseration bred frustration. Concerned residents advised St. Paul Mayor George Vavoulis that “unless an anti-poverty program [was] developed for the Negro community . . . , ‘a Watts or a Chicago or a Boston,’ could happen [here].” This warning was clearly a reference to the spate of urban rebellions that took place across the country in the 1950s and ’60s in response to persisting unequal distribution of power and resources in Black communities. In an attempt to harness this discontent for constructive ends, a group of St. Paulites began organizing at the grassroots level.

Origins of the North Central Voters League

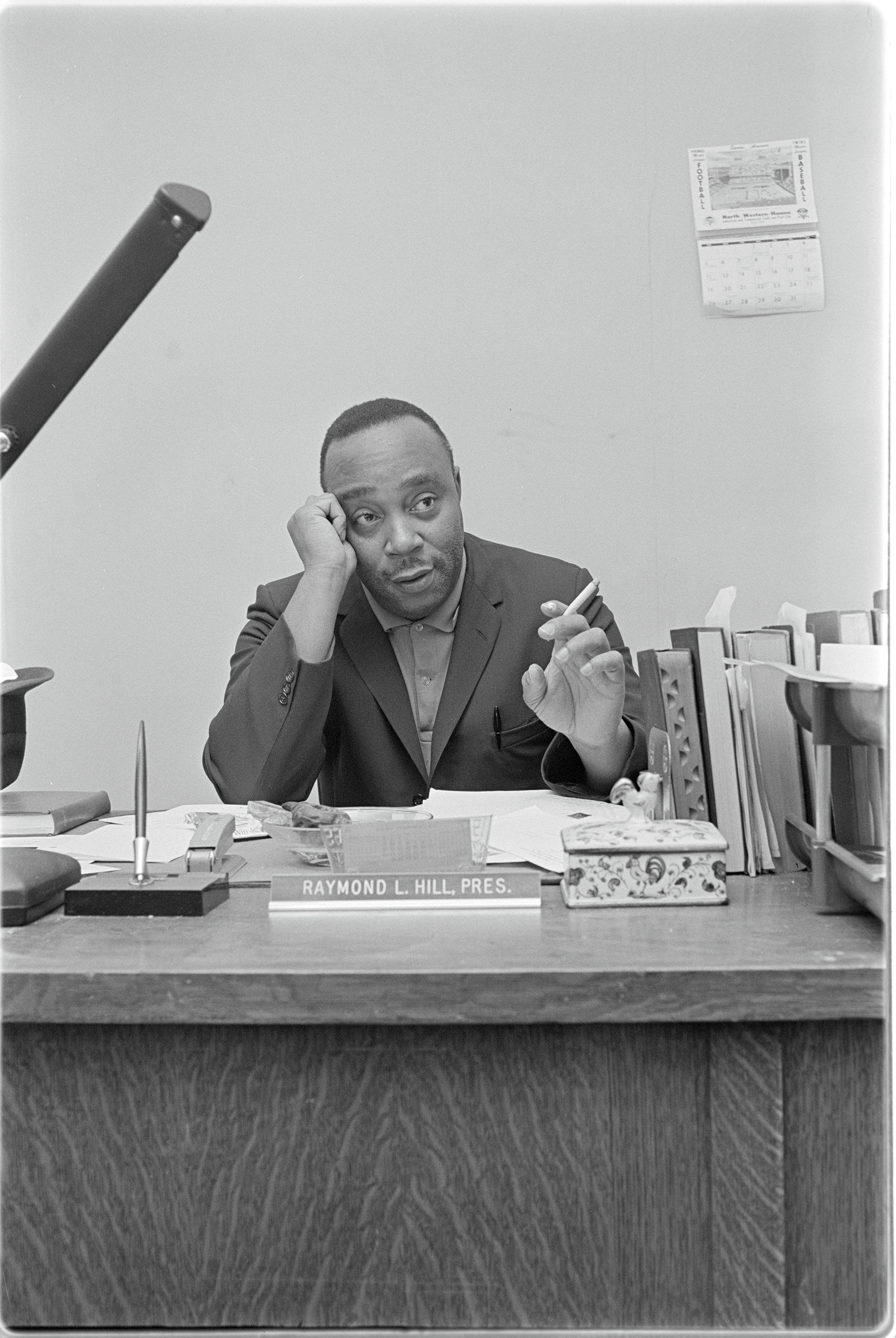

In November 1963, a unique organization was “born on a street corner . . . when six men met to talk about community improvements and the ‘vacuum’ of concern emanating from downtown.” This group included Raymond Hill, a waiter at a Minneapolis hotel; Lester Howell, an unemployed waiter and sometimes janitor; Robert Anderson of the St. Paul Housing Authority; and three men employed by the railroad at Union Depot—James Thomas, retired Red Cap; Richard Travis, a dining car waiter, and Jack Payne, a Pullman porter.

The men collectively decided the community needed “an organization that will do something for us.” They sought:

. . . some place for these kids to play. . . . some kind of a library so [the] children can grow up with a little pride, and some knowledge of what their parents are doing for them.

The group concluded that the people at city hall “don’t care about any one person but they sure listen to a lot of people, especially if they are voters.”

Chipping in five dollars each, the organizers sought to make concrete the “dream of a community in which all . . . would be able to make a contribution. A dream where everyone would receive equal representation under the law.” They took these collective funds and their plan to the Gopher Elks Lodge. The Elks offered them space to meet and wished them luck. Thus, the North Central Voters League (NCVL) came into existence.

According to NCVL President Raymond Hill and Vice President Jesse Miller, the league was “the ‘new voice’ of the St. Paul Negro community which speaks for ‘the man on the street, the poor people here.’ ” Twin Cities griot Mahmoud El-Kati explained that the members of the NCVL were mostly working class, representing “a variety of occupations in the workaday world, [with] a disproportionate number [having] backgrounds in the railroad industry.” A few members were college educated, and most were middle-aged and older. Elder El-Kati’s mention of railroad workers in the NCVL is significant given the militant labor activism that punctuated the railroad and hospitality industries in the early twentieth century. League members who had experience in the railyards and restaurants of the Twin Cities very likely would have been aware of or even had experience with this activism. The local, collective forms of organizing that typified the early twentieth century labor movement acted as forerunners to the militant, grassroots approach that informed the NCVL’s early days.

The league insisted that “. . . the time ha[d] passed when the poor should merely ask for help,” contending that they must instead make clear demands. The NCVL strongly believed such demands “must originate in the poor community” and claimed the league would act “to fill a need, to meet the wishes and the aspirations of the people.” In the process, they would give “ghetto-dwellers ‘an opportunity to speak, to act, to contribute, to belong.’ The Voters League [was] a bulwark.” With this commitment to carrying out the will of the community, the NCVL embarked on its first focused project.

Influencing St. Paul Politics

As its name suggests, the NCVL initially concerned itself with voter registration.

They begged people to register; they argued with people until they registered; they borrowed cars to take people down to City Hall to register. On October 13, 1964, they had registered 1,054 people, most of whom had never registered before in their lives.

The process of registering voters was no easy feat given that, in early 1964, the league had less than twenty members. Nonetheless, “in one day, they transported 232 persons to the voter registrar in three chartered buses.” Not content to simply register voters from the Selby-Dale neighborhood, the NCVL also played an important role in bolstering Black candidates’ electoral campaigns.

Earlier that year, on Tuesday, March 10, 1964, resident Katie McWatt secured a nomination for St. Paul City Council. This was a noteworthy development, as McWatt’s election would have made her “the first Negro to win elective office in the history of the Saintly city.” As one of the first organizations to endorse her campaign, the NCVL was the most visible and aggressive supporter of the McWatt campaign on every level. The league also held candidate forums to support McWatt for the council seat. Despite the best efforts of McWatt, her supporters, and the NCVL, she lost a closely contested race in the at-large election that fall. Still, NCVL’s support of McWatt’s campaign helped raise its local profile and set a precedent for supporting future Black political candidates.

Two years after McWatt’s nearly successful run for city council, on March 24, 1966, St. Paul police officer James Mann announced his intention to run for the St. Paul Board of Education, making him the first Black candidate to run for the city’s school board. The NCVL endorsed Mann immediately, and President Hill served as cochair of the campaign committee. The first public rally for Mann’s candidacy was held at a new office location at 739 Iglehart Avenue three days later.

[There, s]ome 150 persons heard Mann criticize the present school board for what he called a ‘flagrant misuse of funds’ in allocation of federal aid. He said money allocated for the Summit-University area was channeled to other schools . . . .

In addition to these denunciations, Mann pointed to de facto segregation in the city’s public schools. Despite speaking to many residents’ concerns, Mann, like McWatt, did not succeed in gaining public office. Undaunted, the NCVL continued its work in the community.

Grassroots Education Programs

The league sought to build a variety of grassroots programs in the Selby-Dale neighborhood. In October 1965, it submitted a proposal to the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), requesting $1.4 million in federal antipoverty funds to create, among other things, educational programming, including adult education and job training. NCVL received $329,000. While certain programs—such as music and some adult classes and typing and office skill courses—ran without government aid, the league’s access to federal funds allowed it to implement a range of educational classes.

The Adult Education Program, a part of the Community Action Program (CAP), offered free courses and included basic education “to teach those who [did] not read, or who want[ed] help in general reading improvement. It [was] also for high school drop-outs. The class [gave] help and instruction in spelling, and arithmetic.” They provided high school equivalency diploma classes, consumer education, and courses in sewing and typing. Through this program, the NCVL also hosted lecture discussion groups on home, family life, and sex education in an effort to strengthen the “general moral fiber of the community.” The first lecture topic was “Proper Sex Education for children,” covering “growing up, going steady, planning for marriage, interfaith marriages, [and] developing sound sex attitudes.”

The league offered a number of educational spaces for youth, as well. For example, the Reading Room, a volunteer program run without federal funds, started with community book donations. The Reading Room committee hoped to offer children reading and other cultural activities that would eventually include music, drama, art, and dancing at the center on Saturdays and some evenings.

Other youth-focused programs included the establishment of daycare centers to provide “social orientation and develop communication skills for children.” By 1966, the NCVL ran daycare at St. James A. M. E. Church and St. Philips Episcopal Church, which were operating half-day morning and afternoon classes. By February 1967, a third center was scheduled to open at the Church of St. Peter Claver. Aside from instruction, the children received checkups from a visiting physician. Staff sought to enhance its educational approach by attending the Project Head-Start convention at Bethel College in June 1964, where they joined other daycare providers from around the Twin Cities to learn more about the unique phases of childcare, the importance of community involvement, and arts, crafts, and activity ideas. The NCVL reportedly impressed the other convention attendees with its proposed cultural enrichment program.

Beyond their work with younger children, the NCVL focused its energy on reaching teenagers and young adults. In June 1967, the league started the Teens in Action program, under the direction of Donna Frelix. The goal of this program was to reach 400 teens between the ages of thirteen and seventeen. That summer, the young people went horseback riding, swimming, bowling, picnicking, and camping. “One group made a trip to the Tyrone Guthrie Theater to see the Greek tragedy ‘The House of Atreus.’ Another formed a glee club.” A girls’ judo class was soon added, as well.

One of the unique aspects of Teens in Action was the fact that the teens, themselves, helped supervise the program. Twenty group leaders were individually tasked with recruiting “10 youngsters from the street corners, pool halls and empty lots, where the hard-to-reach youths with nothing to do usually are found.” NCVL leaders would “send guys down to the pool hall who [knew] the languages . . . with all the different slang” and who could relate to the demographics the league wanted to reach. Robert (Bobby) Hickman, a thirty-one-year-old group supervisor, noted that the program’s staying power came from the fact that “when [the youth] know there’s someone who cares . . . they usually come back.” While programs like Teens in Action sought to engage youth through leisure and recreation activities, an equally important area of NCVL intervention among young people was employment.

Creating Employment Opportunities

Critical of how the “power structure” worked to satisfy a few community members, while leaving the majority of the community “hidden inside ghettoes, hidden behind charts, graphs and statistics,” the NCVL coordinated with Mayor Thomas Byrne’s office and local businesses to facilitate job placement for youth and adults in St. Paul’s Black neighborhoods. In August 1966, NCVL’s Donald Johnson spoke at a meeting with the mayor, Gov. Rolvaag, “several large companies, the St. Paul Chamber of Commerce, organized labor and other public officials.” The purpose was to “ease racial tensions through expanded job opportunities” and appeared to yield quick results when, that same day, the St. Paul Youth Opportunity Center (YOC) reported that “about 50 job offers had been received, mostly for unskilled positions in everything from foundry work to grocery store carryout.” The following summer, the mayor met with representatives of twenty St. Paul businesses, asking them to “provide jobs for three weeks for up to 100 youths 13 to 19 years old.” Organizations including NCVL helped recruit and refer youth to these opportunities.

In February 1968, Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M) announced it would open a job training center at a facility that produced coated abrasives and tapes “for unskilled minority and ‘other disadvantaged’ groups.” In its planning, 3M consulted with the North Central Voters League and other organizations, which were to refer prospective trainees. That May, the 3M training center opened,

. . . accommodat[ing] 75 trainees in three eight-hour shifts, and [was] staffed with a special 12-man teacher team. Anyone taken in as a student at the center immediately [became] a 3M employee ‘in training.’ [The new workers] receive[d] benefits, including hospitalization, life insurance, holidays, vacations, rest periods, and service credit.”

Beyond recruiting and referring residents for employment opportunities, the NCVL played a crucial role in fostering community support for the establishment of new job-training institutions. In 1966, Minneapolis-based pastors James Holloway, Stanley King, and Louis Johnson announced their intention to create the Twin Cities Opportunities Industrialization Centers (TCOIC) program. From its conceptual beginnings, TCOIC counted on the support of the NCVL. The ministers initially aspired to have three locations: one in North Minneapolis, one in South Minneapolis, and “one in St. Paul with the cooperation, it hope[d], of the North Central Voters League.”

That fall, the TCOIC Steering Committee met with NCVL staff to forge a cooperative relationship. The league held a public meeting at its headquarters on September 21 to spread awareness of TCOIC and its potential benefits.

The NCVL’s support for TCOIC appears to have had some success in cultivating cooperation from Black St. Paulites. Editor-publisher Cecil E. Newman pointed to “more than 1,000 signatures from STP residents supporting the TCOIC,” along with financial help from the community, including a $263 gift from the Auxiliaries of Mount Olivet Baptist Church. To further assist the TCOIC in finding its footing, the NCVL, along with other organizations, conducted a skill survey in the community to better determine what specific training programs were needed. This hands-on approach, demonstrated in its aid to the TCOIC, typified all league work, including efforts to secure employment opportunities for community members, impact local politics and education, and improve life in St. Paul, generally.

The NCVL’s Longer Legacy

The programs and approaches mentioned above are only a sample of what the NCVL offered its community during the mid-to-late-1960s. Other initiatives included an immunization clinic held on the first Wednesday of every month; a women’s auxiliary program, which helped at-risk residents perform daily tasks; advocating against the expansion of police power in the city; helping organize food drives for impoverished families in Mississippi; summer field trips and recreational activities for children; a “leadership seminar to create a common front among churches and fraternal and other organizations;” holding space for activists from the wider, national civil rights movement to publicly present their activities and experiences; a Wednesday night forum in which attendees discussed “issues of the day,” such as the environmental movement; and an attempt to create connections between the Black and Indigenous communities of the Twin Cities.

NCVL members committed themselves to changing living conditions in St. Paul, promising consequences if city officials and business leaders ignored their demands. To ensure that those in power took them seriously, the league had “a direct action committee . . . whose sole responsibility [was] to put into operation plans that we have in the files in case we run into any difficulty. One phase of it would be . . . public demonstrations, and rent strikes.” This holistic agenda not only demonstrated concrete, on-the-ground outcomes while the NCVL was active, but also acted as a catalyst for later, everyday Twin Cities establishments.

In the midst of this progress, however, the NCVL’s community presence began to wane following accusations of financial impropriety in 1968. Between May and October, the Ramsey County Citizens Committee (RCCC)—the designated overseer of county antipoverty programs by the OEO—took over the league’s daycare centers, as well as its employment and community service programs.

One allegation RCCC officials leveled against the NCVL was that “league officers charged food, principally spare ribs, to the child daycare project over a long period of time and then sold the ribs at Saturday night barbecues at the league headquarters to raise funds for other organization activities.” According to these same officials, there existed no documentation regarding the amount of funds raised nor any explanation about what the league used those funds for. The RCCC also claimed that $22,263 in federal funds were unaccounted for and alleged NCVL misuse of funds from 1966 and 1967.

The RCCC later offered to allow the NCVL to resume its role in executing federally funded programs if it agreed to refund $23,833 of supposedly misspent funds and dismiss then NCVL leaders Hill and Miller. Robert Anderson, chairman of the league at the time, stated that such an agreement was of no benefit to the NCVL or the public, and the offer was rejected. Anderson declared that “members and leaders of the Voters League had been accused of thievery. . . . and demanded that the accusations be substantiated . . . or withdrawn.”

While both sides eventually agreed to an independent audit and confirmed that the league would accept responsibility for the outcomes of that audit, disaccord persisted between the organizations regarding the extent to which the RCCC would control the NCVL’s programming. The league filed two lawsuits against the RCCC for rent recovery, unpaid salaries, and punitive damages. In 1970, the matter was settled out of court when the RCCC paid Hill and Miller a total of $5,000, but the NCVL’s ability to offer community-oriented poverty programs did not recover following this multi-year conflict.

While this very public row seemed to have diminished the league’s own role in St. Paul, the half-decade of work the NCVL did in the community had long-term effects that continue to positively influence the Twin Cities today. Some of the programs the NCVL created or supported went on to become well-established institutions in the Twin Cities. The TCOIC, for instance, merged with the vocational program Two or More in 1996 to form Summit Academy OIC, which currently runs two campuses in North Minneapolis.

According to Elder El-Kati, from an electoral perspective, we can understand the McWatt and Mann campaigns as “the beginning of the continuum of African American candidates running for city council” and other public offices. Present and past Black elected officials in St. Paul, including current Mayor Melvin Carter III and city council members Anika Bowie and Cheniqua Johnson, are, thus, part of a tradition started by community ancestors such as McWatt and Mann and supported, in early stages, by the NCVL.

Another NCVL contribution is its role in guiding emerging activists who went on to influence citywide grassroots politics. Bobby Hickman, for example, worked with the NCVL’s Teens in Action program in the summer of 1967. One year later, he founded the Inner City Youth League (ICYL). The ICYL implemented long-term art education programs for youth throughout the late twentieth century, while also intervening in issues concerning employment and policing. In addition to Hickman, the NCVL helped launch the public career of Elder El-Kati. El-Kati moved to St. Paul from Cleveland in 1963 and got involved with the NCVL during McWatt’s city council campaign. League members eventually asked El-Kati to teach community-oriented Black history classes. He explains:

They opened the [new] Hallie Q. Brown Center . . . and said ‘Can we have space to teach Black history?’ That’s how I got into this thing. They did that. Next thing I know I was at this church, that church, that church. . . They the ones started my little . . . excursion . . . little trek in the Black history experience.

El-Kati subsequently became one of the most stalwart educators in the Twin Cities. Among seemingly countless contributions, he helped create the Department of African American and African Studies at the University of Minnesota, taught history at Macalester College for decades, led the education program at The Way community center in Minneapolis, and helped start and run a variety of grassroots educational programs, such as Asili: Institute for Women of African Descent—a project that, itself, spawned a variety of other organizations, including the African American Academy for Accelerated Learning, Imhotep Science Academy, the Cultural Wellness Center, and Papyrus Publishing, Inc.

We Cannot Forget; Work Continues

The North Central Voters League committed itself to becoming an institution of the community, making important interventions in the day-to-day lives of residents by listening to their needs and helping to create opportunities that did not previously exist. Over just a few years, the league implemented a variety of programs aimed at improving the lives of low-income Black St. Paulites.

The influence of the NCVL was not ephemeral, however, as we continue to live in the wake of what the league, its institutional forbears, and its activist progeny have wrought. As community members who occupy a world inherited from our elders and ancestors, we must recognize early advocacy groups like the NCVL that have unapologetically strode “down the hard path of conscientious endeavor” in an attempt to leave us with a community that is a little more livable.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Elder Mahmoud El-Kati for generously sharing his experiences with the NCVL with me, as well as for his enthusiastic support for the writing of this article. Peter Rachleff, formerly of the East Side Freedom Library, was the first person to make me aware of the NCVL’s history, for which I am grateful. My sister, Alex Bledsoe, offered helpful and constructive feedback on an early draft of this article. The attendees of the Nu Skool of Afrikan American Thought on September 27, 2024, were an important audience for the ideas presented in this article. The Minnesota Historical Society staff assisted in finding a number of the sources cited here. Any errors are mine and mine alone.

Adam Bledsoe is an associate professor in the Department of Geography, Environment & Society at the University of Minnesota. He is a scholar of the African Diaspora and is primarily concerned with the ways Diasporic populations analyze and seek to make interventions in the world around them.

- Year

- 2024

- Volume

- 59

- Issue

- Number 4, Fall 2024

- Creators

- Adam Bledsoe

- Topics