The Women Who Have Shaped the Ramsey County Historical Society

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 1, Winter 2025

- Creators

- Andrea Swensson, Youa Vang, Meredith Cummings

- Topics

Seventy-Five Years of Making History

By Andrea Swensson, Youa Vang, Meredith Cummings

For the past year, Ramsey County Historical Society has focused its lens on its own past in observation of its seventy-fifth anniversary. Founded in April 1949 by community historian Ethel Stewart and her fellow officers from the St. Anthony Park Area Historical Association,1 and wholly inspired by the value Stewart saw in a nineteenth century farmstead inhabited by Jane DeBow Gibbs and her husband, Heman, Ramsey County Historical Society’s mission has been shaped by determined women working tirelessly to preserve important stories.

From the founding of this very magazine by Virginia Brainard Kunz sixty-one years ago to the countless others who have since contributed to the magazine, collected artifacts, created exhibits, and served on RCHS’s various boards and committees, women have been at the heart of this organization at every step of its now seventy-six-year story.

Women have been underrepresented in academic historical studies, though some progress has been made over the past half-century. In 1966, only 27.9 percent of master’s degrees and 12 percent of doctorate degrees in history were earned by women, while in 2014 those numbers had risen to 48.9 percent of master’s degrees, and 42.9 percent of doctorates in the discipline.2

On the local level, those trends are subverted by the large number of “amateur” female historians who have taken it upon themselves to dig into their local communities and teach themselves how to properly archive materials, display artifacts, and navigate the bureaucracy of preserving important buildings. And yet even in these smaller institutions, the historic figures tied to each home or landmark are most often men, to an overwhelming degree. Nationwide, only four percent of historic landmarks are designated for women.3

Considering these statistics, Ramsey County Historical Society’s determination to uplift the story of Jane DeBow Gibbs at the Gibbs Farm is significant. “We always say Jane and Heman—it’s never Heman and Jane,” remarked Gibbs Farm director Sammy Nelson. “She’s the star of our story.”

“We know so much about the women who lived here because they left a lot of letters and records,” added Janie Bender, the manager of youth programs at Gibbs Farm. “For all the houses in the Twin Cities that have been preserved, there aren’t any others that are specifically focused on a woman or a woman’s story. That’s really unique.”

At this milestone moment when RCHS pauses to reflect on its own story, it is undoubtedly a story of women persevering through challenges to connect the past to our present moment. These are just some of the many remarkable women who have made the organization what it is today.

—Andrea Swensson

Jane DeBow Gibbs, Ida Winona Gibbs, Abbie Gibbs Fischer, and Lillie Belle Gibbs Le Vesconte

It’s interesting how a single event from the past can determine the version of history we know in the present. Around 1834, the mother of six-year-old Jane DeBow died. A missionary family brought the youngster west, setting the course of history. While Rev. Jedediah Stevens and other missionaries attempted to establish a relationship with members of Cloud Man’s Village at Lake Calhoun, known today as Bde Maka Ska, Jane (about 1828-1910) happily played with the Dakota children there, making friends and learning the language. As a teenager she moved to Illinois, where she met and married Heman Gibbs, then traveled back to the newly formed Minnesota Territory in 1849 and purchased land. Before long, Jane unexpectedly reconnected with her now-grown Dakota companions, whose ricing trail ran from the Minnesota River to Forest Lake and intersected the Gibbs homestead, which was established on Dakota land.

This story is serendipitous and may have been lost to history had Jane’s children, particularly her three girls, not worked to preserve it. Daughter Abbie (1855-1941) lived at the two-story farmhouse her entire life. She changed little at the property, even as life in the early twentieth century brought new innovations and technology. When the home was saved in 1949 (see Ethel Stewart entry), the homestead looked much as it had nearly a century earlier.

Jane’s oldest daughter, Ida (1852-1922), was an avid letter writer, and her correspondence to her sisters has helped researchers understand the nuances of their daily lives at the turn of the twentieth century. Jane’s youngest daughter, Lillie (1865-1945), was the family chronicler. She left behind written examples of school assignments and drawings from her childhood (see Terry Swanson entry), and as an adult, documented her mother’s remarkable story. The history of this early Minnesota family is preserved today and shared in numerous books, articles, and at Gibbs Farm—all because of a single event that led to the rest of the story.

That doesn’t mean history is set in stone. RCHS recently learned that Jane, in her later years, (knowingly or unknowingly—we aren’t sure) participated in an early science experiment in 1897. Ernest Hummel, a St. Paul watchmaker who had created a telediagraph—an early telegraph—conducted a test at the offices of the St. Paul Globe. He succeeded in sending two photographs through the machine. He chose one photo of Albert Scheffer, a local businessman with ties to the paper. He also transmitted the image of “[Mrs.] H. R. Gibbs,” as the paper noted. RCHS was unaware of this history until contacted by an historian from France.4

Ramsey County Historical Society exists because of the preserved history of the Gibbs family—saved in large part by the Gibbs women.

—Meredith Cummings

Ethel Stewart

Ethel Stewart (1879-1959) said, “No!” In 1942, when the University of Minnesota announced plans to demolish the old Gibbs farmhouse, near Larpenteur and Cleveland avenues (on land the U had recently acquired), Stewart and a small group of citizens from St. Anthony Park were determined to block the move. It took more than a simple “No” to win the fight. In fact, it took nearly seven years of negotiations, offers to move the house elsewhere, collaboration with a Gibbs family member, and an appeal to the Ramsey County Board of Commissioners before the group’s informal St. Anthony Park Area Historical Association (SAPAHA) got close to a “Yes.” There was just one more hitch: The SAPAHA was not incorporated nor was it a county-wide entity. In an emergency meeting, association members voted to incorporate as Ramsey County Historical Society in 1949. The commissioners said “Yes.” Funding was approved. The rest is history.5

Local historian Steve Trimble researched the “activist” a decade ago. Early evidence of Stewart’s interest in history appears in high school speeches and college papers, and she purposely incorporated history into her work as a teacher.6 Her work continued as she and the members of the new society fundraised and convinced generous donors to support the opening of Gibbs Farm Museum in 1954.7

As organizer, historian, and curator of the nascent Ramsey County Historical Society, Stewart was so integral to the organization that the board of directors met at her house and she stored many of the first RCHS artifacts in her home. After she passed on October 7, 1959, the president of RCHS at the time, Hal E. McWethy, wrote that, “The large quantities of exhibits, books, documents and maps found in Mrs. Stewart’s home after her death were immediately moved to the [Gibbs Farm] Homestead. These exhibits and books, as well as all other exhibits possessed by the society have now been carefully inventoried in a permanent record.”8

Writing in one of the earliest RCHS newsletters, Stewart declared: “To be of real value a county historical museum should not merely be a variation of many others of similar nature scattered all across the country, instead it should make some significant contribution to the understanding of the changes in life, habits and people within its own area. It is hoped that such will be the case in the unique presentation of the evolution of pioneer farm home building in Ramsey County as typified in the restoration of the Gibbs homestead.”9

As the organization closes the chapter on its first seventy-five years, Stewart’s steadfast commitment to saving the Gibbs Farm and laying the groundwork for the historical society continues to inspire the employees and board members of RCHS. Perhaps the former director of the Minnesota Historical Society, Russell W. Fridley, said it best when eulogizing Stewart after her death:

Among Mrs. Stewart’s beliefs was an abiding conviction that an appreciation of history was urgently important to one’s existence. The force of this belief found expression in the irrepressible and contagious enthusiasm with which she met the manifold problems and assignments that face every historical organization. Even at an advanced age and in ill health, her interest in historical work and in the Ramsey County Historical Society and its welfare never waned. Her interest retained a remarkable consistency and vitality at all times. When all is said and done, all of us are indebted to this grand lady for her unique contribution in Ramsey County and the State of Minnesota.10

—M.C. and A.S.

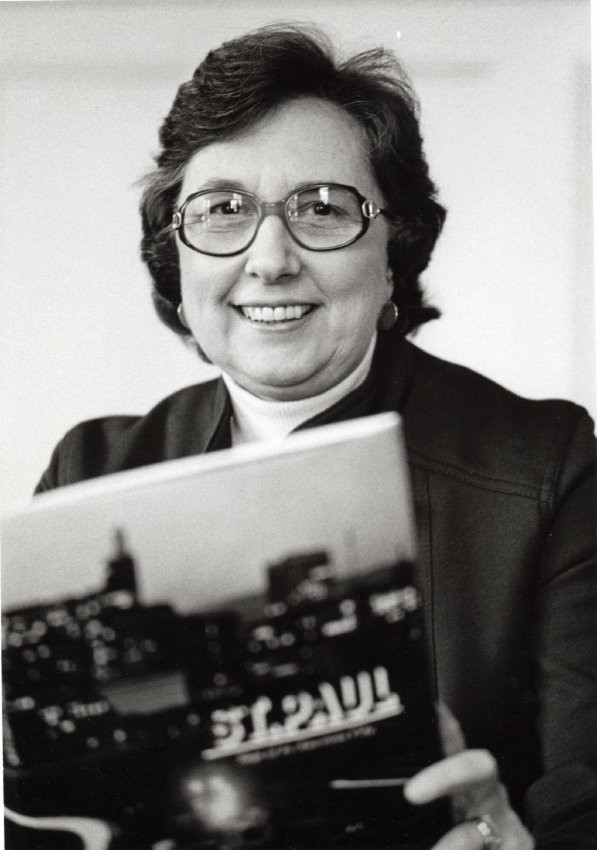

Virginia Brainard Kunz

“Stick with the facts, Max!” So insisted Virginia Brainard Kunz (1921-2006) as remembered by members of the RCHS editorial board.11 Kunz served as the organization’s executive secretary/director for twenty-seven years. In 1964, she founded Ramsey County History magazine, serving as its first editor for over forty years.

The “facts” mantra was likely engrained in Kunz thanks to her education as a journalism major at Iowa State University. After college, she returned to her home state of Minnesota, becoming one of the first women journalists at the Minneapolis Star during World War II.12

Stepping into roles mostly assumed by men didn’t phase Kunz. Anne Cowie, who worked as Kunz’s researcher at the society, remembers her first boss as a powerhouse, “cajoling county officials, soothing board members, and singing [RCHS] praises to anyone who would listen.”13

Kunz was tireless. She authored fourteen history books between 1966 and 2004 along with countless articles. As editor, she worked with a miniscule budget, searched out local history that told a good story, and mentored her authors through the publication process. Under Kunz, the magazine won two awards of excellence from the American Association for State and Local History. John Lindley, who assisted the editor with the magazine for seventeen years and stepped into her role as the society’s second editor after her death, said, “Virginia was the engine that made Ramsey County History go. She had a vision of what a county historical society magazine could be.”14 That magazine—her legacy and a gift to readers of history—just celebrated its sixtieth birthday. Thank you, Virginia Brainard Kunz.

—M.C.

Anne Cowie

Anne Cowie is an RCHS legacy. Her father, Henry H. Cowie Jr., was a member of the society’s board of directors. So it may not have been surprising when his daughter, Anne, followed in his footsteps and volunteered with RCHS. What was surprising was her age. She was seventeen when she penned her first article for the society, “Marshall Sherman and the Civil War: St. Paul’s First Medal of Honor Winner,” in 1967. Interestingly, Henry wrote his first—and only—article for Ramsey County History magazine the year prior. A lawyer, his piece was titled “Minnesota’s Libel Laws.” Anne would continue to take after her father when she eventually earned a JD from William Mitchell College of Law.15

RCHS Executive Director Virginia Kunz hired the younger Cowie to create two urban history exhibits beginning in 1974. She was twenty-four, still pursuing her education, and earning $4.25 an hour at the society. At the time, RCHS had a small office tucked in a corner of what would eventually become Landmark Center. The building was scheduled for a complete renovation, but it had not started in earnest, so Cowie produced the exhibitions in the north lobby—one on urban homesteading in Irvine Park and another featuring a circular display that presented the history of St. Paul in the 1850s, complete with an overlay of the city 125 years later. In 1976, she received a grant to host expert speakers on the history of the Mississippi River, and she produced a related video.16

By the 1980s, Cowie had moved on, working as a Ramsey County law clerk and raising a family. Still, she joined the RCHS Board of Directors and served on the society’s editorial board. She also wrote multiple book reviews and additional magazine articles. Cowie and Laurie Murphy (also an RCHS legacy) were the only women members early on. Cowie quickly realized the men mostly ignored the young ladies. That’s when she learned to stand up, say her piece, and make sure she was heard. Her insistence, patience, and ability to view issues through multiple perspectives, along with her dry sense of humor soon garnered respect from board and committee members.17 In 2006, she was named editorial board chair—a position she held for fifteen years, overseeing sixty-two issues of the magazine. She remains a respected supporter of the organization fifty-seven years on.

—M.C.

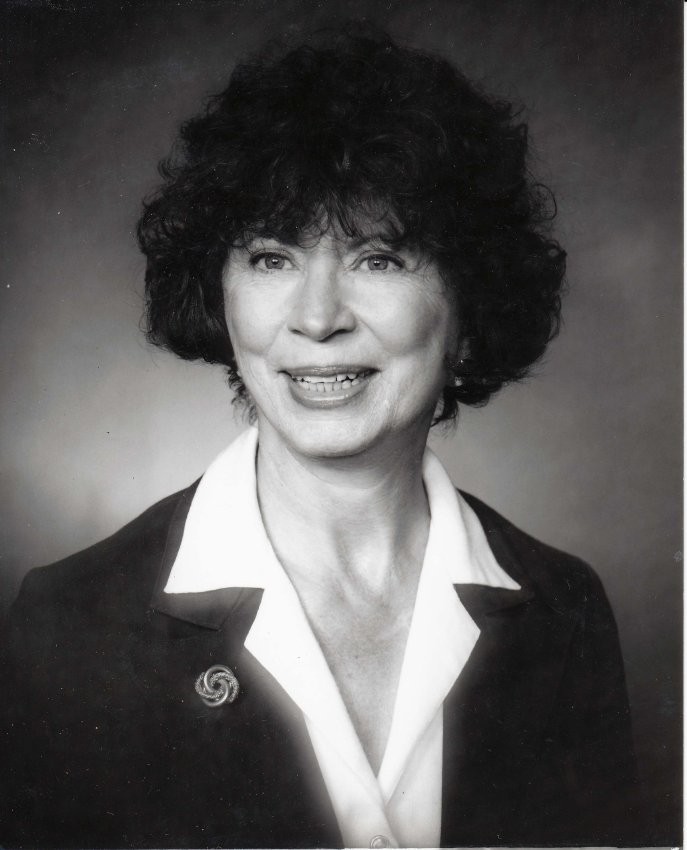

Priscilla Farnham

The world has changed many times in the nine decades that Priscilla Farnham has been alive. “I was quite old when I took on the executive director [1991-2011] role for Ramsey County Historical Society, and I left when I was about eighty years old, but it was time to move on,” she shared.18

Some leaders express concern over the work they left behind, but Farnham falls into the reconciliation phase when she talks about her time at the organization. In 1991, the society’s work centered around publications, a hat tip she sends to the first editor Virginia Kunz, and Farnham didn’t feel it shifted until she hired Mollie Spillman into the director of collections and exhibitions position. With Spillman in place, the preservation of items—and history—changed focus in the work that was being carried out.

“I was lucky to have good people,” she states, weighing her words carefully as she pulls from her memories. “Anyways, I was better at managing projects.”

One project of note was developing the Dakota program at Gibbs Farm. Farnham admits that even as late as the early 2000s there was very little that the society was doing to preserve the Indigenous culture, whether due to lack of understanding or lack of resources. Ramsey County was ripe with the history and culture of the Dakota that have inhabited the land. Thus, the plan was to develop a program with Terry Swanson, director of Gibbs Farm at that time, around those stories.

A board was formed to ensure the developed work was culturally sustaining, and Farnham admitted she made some mistakes along the way. “The first thing I did was ask about canoes, and the advisory board was very polite. There was a big silence in the room, and after a while, someone said, ‘Dakota didn’t use canoes. They used dugouts. Ojibwe used canoes.’ I didn’t know that.” It was through the risk of making mistakes and leading with curiosity that fed the work Farnham did. That forever changed the work of RCHS and its future.

—Youa Vang

Joanne Englund

Joanne Englund’s work at Ramsey County Historical Society was all voluntary—as she did have a day job. With a degree in government administration and writing from Metro State University, Joanne wrote grant applications and program evaluations for the City of St. Paul and St. Paul Public Schools for over two decades.19

She put her administrative, writing, and leadership skills to work for RCHS for twenty-five years beginning in 1989 when she joined the board of directors. Before long, she was the first woman to chair the board under Virginia Kunz. Englund also chaired the Gibbs Farm committee for years.20

“Joanne was [and still is] unwavering in her loyalty to the organization . . . logical in her thinking. . .” Cowie added that this quiet, unassuming woman could look at the big picture facing the society, pinpoint the challenges, and devise solutions.21 Her connections with city government and grant writing were also assets to RCHS. And, of course, because writing is what she does, she penned three articles for Ramsey County History, including a brief memoir of family life on St. Paul’s East Side, then Roseville, in the 1950s and ’60s.22

—M.C.

Mollie Spillman

In her little alcove in Landmark Center in downtown St. Paul, Mollie Spillman can be found at her desk, glasses often pushed to the top of her head as she is responding to emails or perusing a piece donated from someone who has a connection to Ramsey County. Spillman began her career as director of collections and exhibitions for the organization in 1994. The first decade of her career was spent discovering and uncovering what treasures were housed in the collection.23

“Where my office is now, there was just stacks of things. It was just a snake trail, because no one had done it for so long,” she remembered.

In the last thirty years, the role has changed a lot, and Spillman and her work ethic were a big part of how things were molded into place. Much of the challenge was learning to get the work done and define processes with no staff. Spillman’s talents lie in her methodical way of approaching her work, meticulously looking at each little aspect of the job, gathering her collective knowledge that is stored in the recesses of her brain and rendering it out to the world, so the public can understand collections in layman’s terms. What is not easily definable is how Spillman is so good at bridging gaps and harnessing people and their stories. She attends to everything with an easy-going manner that puts everyone at ease when she enters the room, her smile and laughter lighting up any space she inhabits.

“Part of my job is relationship-building with interns, board members, and colleagues, but also potential donors to the collection. A fun aspect of my job is learning all of these stories that come with the work. You have to draw the stories out of people, because even if the item is a cool thing, how does it relate to us and what story does it tell?” For in the end, we are all just stories.

—Y.V.

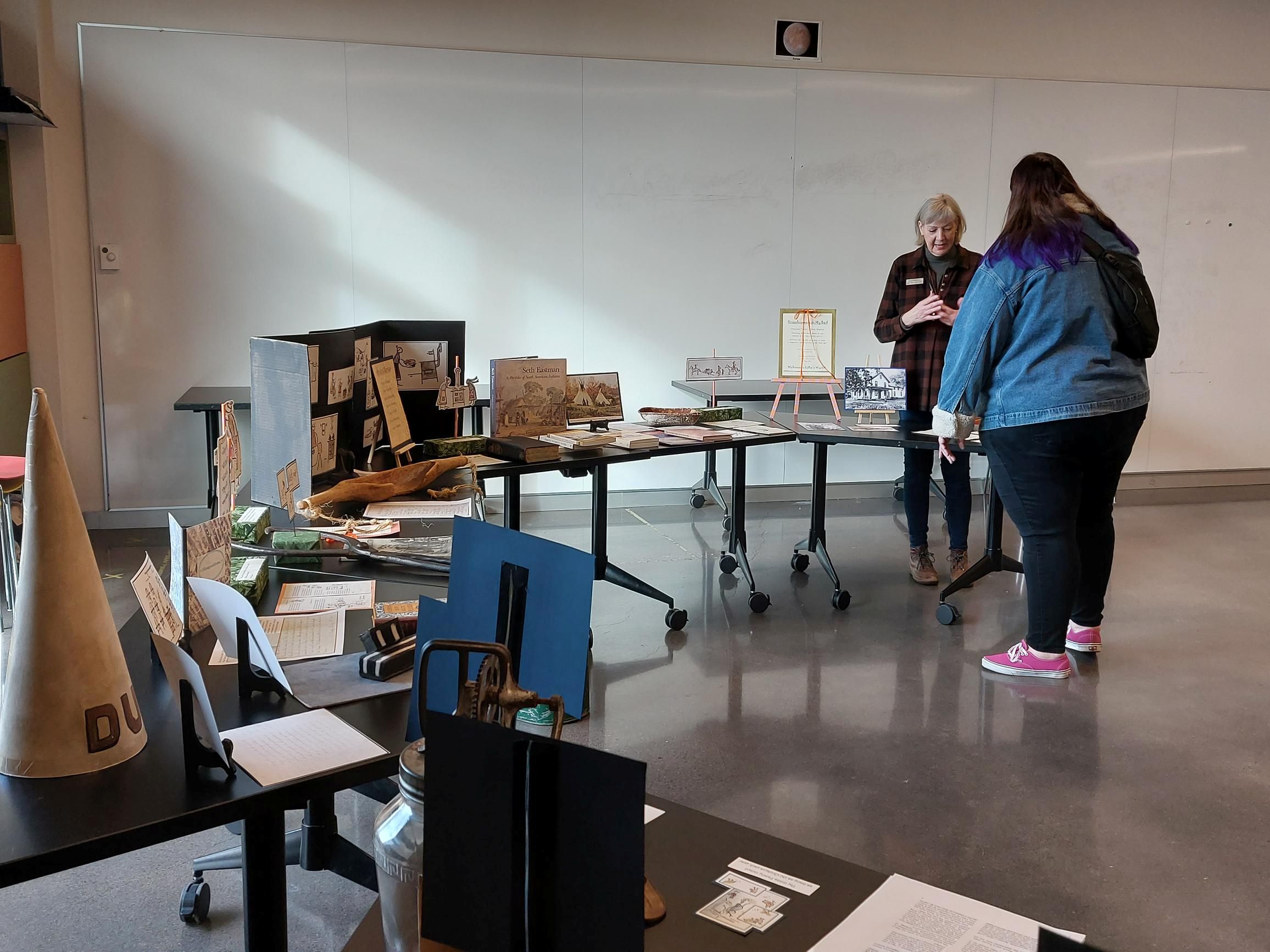

Terry Swanson

In 2023, the Bell Museum of Natural History hosted a day for collectors to share their treasures with curious guests. Terry Swanson, a bubbly blond septuagenarian with endless energy and creativity displayed her book research across five tables.

“Boring,” you say? Not in the least! You see, Swanson (1950-2024) wrote and published a historical fiction children’s book a few years ago with RCHS—Grasshoppers in My Bed: Lillie Belle Gibbs–Minnesota Farm Girl–1877. It’s the story of a real girl who lived on a farm that, interestingly, happens to stand across Larpenteur Avenue from the Bell in Falcon Heights—yes—Gibbs Farm! As the former manager at Gibbs Farm, Swanson spent hours in the society’s archives “getting to know” the family, so she could share what she learned with guests.

Why? Because when curious youngsters visited the old farmhouse, the replica soddy, and the barn animals around the property, they’d often ask, “What was life really like on this farm so long ago?” Swanson was determined to answer that question by focusing on the life of ten-year-old Lillie, the youngest Gibbs daughter.

And so, back at the Bell, Swanson displayed copies of Lillie’s fourth- and fifth-grade essays—including one titled, “What I Did Last Summer.” She transported Lillie’s life in 1877 to 2023, with examples of the girl’s handwriting, her doodles in a dictionary, and her name carefully added to the inside cover of the family Bible. Swanson displayed butter churns, old-fashioned coffee makers, and farm implements, along with colorful pop-up characters designed for the book by illustrator Peggy Stern. Swanson could easily capture the curiosity of passersby. That’s when she was happiest—when she could share her knowledge with others.

The trained public historian demonstrated this throughout her life, serving as program and site manager at Gibbs Farm from 2007 to 2016 and as the director of collections, education, and programs at the American Swedish Institute before that.24 She also served as a volunteer instructor with the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) at the University of Minnesota. Of course, she wasn’t always the teacher. She was more often the student—a self-proclaimed lifelong learner, always looking around every corner to gain more insight and knowledge of the world around her.

—M.C.

Mari Oyanagi Eggum

Service has played a large role in Mari Oyanagi Eggum’s life. First, in administering and facilitating grants for a foundation of former Governor Elmer Andersen all while juggling two young children. Second, in serving on the Ramsey County Historical Society’s board for nine years, the last two of those as board chair.

Advocacy and philanthropy were two skills that were ingrained early on into Mari’s life. “In my senior year of high school, I remember being voted ‘Best All-Around Student’ while my brother was voted ‘Class Clown,’ ” she laughingly recalled over coffee in Summit Hill.25 Eggum grew up in a very white-dominated school, wherein she was one of three Asian people in a class of 400 students.

The gravitation to assimilate was very strong, which brought its rewards and challenges. Eggum recalled her grandparents coming to the United States from Japan seeking economic opportunities and obtaining work building railroads on the West Coast. Her father’s side of the family was interned in camps during World War II, and because her mother’s side had settled in Idaho which was considered far enough inbound, they weren’t affected by the camps. After his release from the camps and integrating back into the world, Eggum’s father followed his brother to Minnesota to eventually settle in St. Paul.

So did they eventually find the economic opportunity they were seeking? “Yes, to a certain extent. My dad’s side of the family ran the local grocery store, so they did fine. In their minds they were doing okay, and my mom’s side of the family ran the town laundromat. They had this culture of hard work that was instilled in them from their parents,” Eggum said.

What endured even more were family values and the passing on of Japanese traditions to the next generation. With no regret, Eggum matter-of-factly shared a story about her younger cousin with whom she grew up, who took traditional Japanese dance and participated in the Japanese Citizen’s League while she grew up in a more assimilated household. The traditions she valued, she kept, while those she had no recollection of, she let go. The one big celebration she holds onto is a New Year’s meal tradition upheld by her grandmother. When she passed away, Eggum and her three cousins continued the tradition. There’s sushi, tonkatsu, dumplings, Japanese salad, and anything Asian they can fit onto their tables. The blended history of these lives is blurred as Eggum folds her grandchildren into these traditions.

—Y.V.

Meredith Cummings

“To be able to tell people’s stories has been really important to me,” said Meredith Cummings, editor of Ramsey County History from 2019 to 2024.26 Although the magazine has now been in circulation for over sixty years, Cummings was only the third editor to step into the role, succeeding John M. Lindley.

She still remembers the moment the editor job was posted online; she sat up on the couch and said out loud, “That’s what I want to do.” Cummings was new to the Twin Cities, having spent the previous twenty-two years working as a journalist, editor, and English instructor in Indiana. The opportunity to learn more about her new surroundings by studying its history intrigued her. “I was an anthropology major. That was my undergrad. And the opportunity to get to know people and what they do in their surroundings, and why they do it and how they do it—that’s history,” she reflected.

In a relatively short amount of time, Cummings fell in love with Ramsey County history and forged connections with many of the community leaders taking on the work of preservation. “I know more people—better—in Ramsey County than anywhere I’ve ever been. I have gotten to meet some fantastic Minnesotans: the leaders, the historians, the researchers, the people who have kept that history alive,” she shared.

Looking back on her tenure, Cummings says she is most proud of publishing the all-Dakota issue, for which she worked with five Indigenous students at the University of Minnesota to compose a three-part history of the Dakota language.27 “I think it’s just a beautiful issue. It was incredibly hard to do. But I feel blessed that I got to get to know the students, and to work with them, their instructor, Šišókaduta, and other Dakota scholars.”

She also became inspired by the work of the women who preceded her at Ramsey County Historical Society, including trailblazers like Ethel Stewart, Anne Cowie, and the founder of this magazine, Virginia Brainard Kunz. “Women saw that that this history was going to be lost and made sure that that it wasn’t. There was a board of men who thought they knew it all, but there were also these women who stood up to them: Virginia stood up to them, and Anne stood up to them.” Over time, this institutional legacy informed Cummings’ own approach to her work. “I used to be very, very shy, no confidence whatsoever. But if you don’t say what you think, you’re going to get trampled. All of these women stood up for what they believed in and said, ‘Pay attention. This is important.’ And I hope that I did that as well.”

—A.S.

Sammy Nelson, Janie Bender, and Clare Holte

From May through October each year, an average of 13,000 to 15,000 school children visit the historic Gibbs Farm to learn about life on a farmstead in the nineteenth century and the Dakota traditions that were upheld by the people of Ȟeyáta Othúŋwe (Cloud Man’s Village) at Bde Maka Ska, with whom Jane Gibbs spent time as a child.

In addition to a constant stream of field trips, Gibbs Farm is also open to the public for tours, classes, and an annual Apple Festival. For much of the past decade, the planning of these activities and the preservation of the site itself has been managed by the same team of three women: director Sammy Nelson, youth programs manager Janie Bender, and volunteer and adult program manager Clare Holte. Their collective knowledge of the farm runs deep, from their knowledge of each Gibbs family member to the agricultural needs of the land each growing season to the innerworkings of their large team of staff and volunteers.

Much like Ethel Stewart once hosted RCHS board meetings in her own home, the Gibbs Farm team is so committed to caring for the animals who live on the farm—including geese, ducks, chickens, goats and sheep—that the livestock is transported to Bender’s family farm in the offseason.28

Bender said she first encountered Gibbs Farm as a child, when she visited the site on a field trip. “I remember coming and being like, ‘I would like to work here someday.’ ” Bender is now on the receiving end of questions from young children visiting the farm, from “Do you live here?” and “Is this real?” to the always surprising, “Where do babies come from?”

For Holte, the most rewarding part of her work is coordinating a team of volunteers to care for the eight acres of land, tending to the orchard and planning out the gardens each year. “We have a Dakota crop garden, and then we have a pioneer crop garden, and my goal is to get as close to historic varieties as we can,” Holte shared.29 She has combed through horticultural society journals and old Minnesota State Fair records to learn more about what nineteenth century farmers were growing.

Though they spend most of their time focused on the day-to-day activities of running a farm and museum, Nelson said that the team takes pride in knowing that they are preserving the story of what she describes as an ordinary family. “Jane and Heman weren’t wealthy. They didn’t invent something super specific. And so it gives people a glimpse at an ordinary life in Minnesota in the 1800s. And then obviously Jane’s tie into the Dakota people is really important, too,” Nelson explained.30 “There are a number of places that talk about Dakota history and culture, and places that have Indigenous folks running those programs. I like to see Gibbs as kind of an intro. Whether you’re a child or an adult, we’re a leading point to get people interested so they can learn more about the Dakota people.”

“I hope people find—no matter their background—some connection to Minnesota’s past,” Nelson said. “You don’t have to be a specific kind of person to feel like you belong here.”

—A.S.

Moving Forward

As RCHS looks ahead to its next seventy-five years and beyond, the organization remains committed to uplifting lesser-known stories and securing women’s place in history. To quote Dr. Heather Huyck, a historian with the National Park Service and founding member of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites: “America’s story makes no sense with half of its participants missing. . . . There is no site that doesn’t have women’s history. If we are to understand who we are and where we’ve come from, we need to know the whole story.”31

NOTES

- “In Memoriam: Ethel H. (Mrs. C.H. Stewart), 1879-1959,” Ramsey County Historical Society News, December 1959, 2.

- “Humanities Indicators and Departmental Survey,” American Academy of Arts and Sciences, accessed February 28, 2025, https://www.amacad

.org/humanities-indicators/higher-education/gender-distribution-degrees-history. - “Where Women Made History,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, accessed February 6, 2025, https://savingplaces.org/womens-history.

- RCHS looks forward to conducting more research about inventor Ernest Hummel and his connection to Jane Gibbs.

- Steve Trimble, “An Adventure in Historical Research: In Search of Ethel Stewart,” Ramsey County History 49, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 6-7.

- Trimble, 3-6.

- Trimble, 7.

- Hal E. McWethy, Ramsey County Historical Society News, February 1960.

- Ethel H. Stewart, “The Gibbs House,” Ramsey County Historical Society News 1, no. 4 (November 1952).

- “In Memoriam: Ethel H. (Mrs. C.H.) Stewart,” 4.

- Laurie Murphy, correspondence with Meredith Cummings, March 16, 2024. According to Murphy, a member of the editorial board for the last thirty-four years, “Virginia always said, Stick to the facts. The facts were crucial.” Other board members concurred.

- “Virginia Brainard Kunz short biography,” in Virginia Brainard Kunz, St. Paul: Saga of an American City, (Woodland Hills: Windsor Publications 1977).

- Anne Cowie, “Growing Up in St. Paul: The Peripatetic RCHS in the Mid-1970s,” Ramsey County History 49, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 8.

- John M. Lindley, “Virginia Brainard Kunz (1921-2006)—A Eulogy,” January 13, 2006, in Ramsey County Historical Society Archives.

- Anne Cowie, interview with Meredith Cummings, October 4, 2024.

- Cowie interview; Cowie, “Growing Up in St. Paul,” 8-11.

- Cowie interview.

- Priscilla Farnham, interview with Youa Vang, December 30, 2024.

- “Joanne Englund,” Linked-in profile, https://www.linkedin.com/in/joanne-englund-22b61a14/details/skills/.

- “Joanne Englund,” Linked-in profile; Cowie, interview.

- Cowie, interview.

- Joanne Englund, “Growing Up in St. Paul: First a Tiny Starter Home, Then a New Post-War Suburb Beckoned,” Ramsey County History 34, no. 4 (Winter 2000), 21-23.

- Mollie Spillman, interview with Youa Vang, January 27, 2025.

- Terry Swanson, Grasshoppers in My Bed: Lillie Belle Gibbs—Minnesota Farm Girl—1877 (St. Paul: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2022), author’s bio.

- Mari Oyanagi Eggum, interview with Youa Vang, December 11, 2024

- Meredith Cummings, interview with Andrea Swensson, February 7, 2025.

- Deacon DeBoer, Eileen Bass, Justis Brokenrope, Ava Grace, Dr. Rev. Clifford Canku, Heather Menefee, and Šišókadúta, “Dakhóta Iápi: A Brief History in Three Parts,” Ramsey County History, 58, no. 3 (Fall 2023), 12-34.

- Janie Bender, interview with Andrea Swensson, January 29, 2025.

- Clare Holte, interview with Andrea Swensson, January 29, 2025.

- Sammy Nelson, interview with Andrea Swensson, January 29, 2025.

- “The History of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites,” accessed February 6, 2025, https://ncwhs.org/about.

Additional Reading

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 1, Winter 2025

- Creators

- Andrea Swensson, Youa Vang, Meredith Cummings

- Topics