Three Extraordinary Years in St. Paul Millinery: 1908, 1909, 1911

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2025

- Creators

- Janice R. Quick

- Topics

Feather Frenzy

By Janice R. Quick

Prosperous St. Paul milliners in the early 1900s periodically traveled to Milan, Paris, and other fashion centers of Europe, where they viewed the latest styles in ladies’ hats and purchased luxurious materials for construction of similar hats at their downtown St. Paul businesses. St. Paul belles flaunted the finest in millinery fashion, and millinery establishments flourished, amid a fashion fad that survived flames and felons, but soon fell to a new fad.

The word “millinery” originated centuries ago, in the fashion center of Milan, Italy. It described fine fabrics and ribbons that came from Milan and were combined to create fashionable hats. Over time, in the United States, the word came to mean the making and selling of ladies’ hats. In St. Paul, a bustling Midwest fashion center in the early 1900s, the word “millinery” described enormous wide-brimmed ladies’ hats that local milliners trimmed with mounds of artificial flowers and genuine bird feathers. Some hats were elaborately decorated with the wings of birds or even entire birds.1

Feather Fashion

Across the United States in the early 1900s, more than 83,000 wholesale and retail milliners decorated hats with the colorful feathers of North American birds, such as pheasants, orioles, ospreys, woodpeckers, blue jays, quails, egrets, eagles, swans, and turkeys. But the most prized plumes were the graceful fluffy feathers of the North African ostrich. Ostrich feathers, in lengths of six inches to three feet, promised elegant height and pomp for any lady’s hat and could be bleached to a stunning white or dyed to complement the color of any gown.2

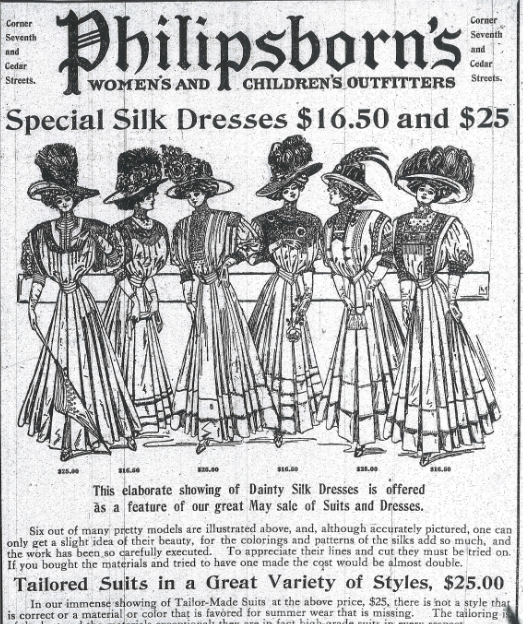

Ostrich farms flourished in California, Arizona, Texas, Arkansas, and Florida, and they supplied coveted ostrich plumes for millinery shops in St. Paul and throughout the United States.3 Hats made of millinery straw and adorned with ostrich feathers were featured in newspaper ads for large department stores and wholesale millinery establishments in downtown St. Paul. Stores with spacious retail millinery departments included: M. Philipsborn Co., advertised as “women’s and children’s outfitters,” located at the southwest corner of Seventh and Cedar Streets; J. Rothschild & Co., a women’s fine clothing establishment at Fourth Street near Sibley Street; and Mannheimer Brothers, a five-story department store that offered millinery, furs, dry goods, shoes, carpets, furniture, and interior decorations, at the northwest corner of Sixth and Robert Streets.4

Prominent wholesale milliners included: Stronge & Warner Co., which occupied a seven-story building at 65-73 East Seventh Street; Robinson Straus & Co., “importers and jobbers of ribbons, silks, millinery goods,” filling 10,000 square feet of floor space in a six-story building at 213-223 East Fourth Street; and S. W. Weiss & Co., 234 E. Fourth Street. These ambitious, prosperous wholesalers actively participated in a Midwest fraternity of milliners and feather merchants, established in 1892 as the Millinery Jobbers Association. Through their leadership and business expertise, the city of St. Paul became known as a hub for feather fashion. In 1908, delegates of the association eagerly accepted an invitation to visit St. Paul and Minneapolis as part of an elite annual convention.6

Feather Fellowship

The Millinery Jobbers Association proudly held their sixteenth annual convention in the Twin Cities, housing out-of-town guests at the elegant Ryan Hotel, located at the northeast corner of Sixth and Robert Streets in downtown St. Paul. On Wednesday evening, May 13, 1908, early arrivals gathered for a smoker in a hotel lounge. More of the forty-three attendees arrived by train, early the next morning, at nearby Union Depot. They arrived from: Chicago, Illinois; Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska; St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri; Dallas, Texas; Des Moines and Cedar Rapids, Iowa; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Fort Wayne and Indianapolis, Indiana; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Louisville, Kentucky. Coveys of spouses and other female guests of these prosperous businessmen likely dazzled onlookers with impromptu style shows as they traveled from the train station to the hotel, conspicuously modeling hats bedecked with showy ostrich feathers.

Attendees from St. Paul included:

- Louis J. Rothschild, 28, residence 496 Holly Avenue; vice president of J. Rothschild & Co., later president of Louis J. Rothschild Wholesale & Retail Millinery;

- Hugo Hirschman, 31, residence 648 Hague Avenue; secretary/treasurer of J. Rothschild & Co.; son-in-law of Joseph Rothschild; later president of Hugo Hirschman Co. wholesale dry goods;

- Joseph Stronge, 45, residence White Bear Lake; president of Stronge & Warner Co. millinery;

- Frank W. Lightner, 40, residence Minnesota Club; secretary/treasurer of Stronge & Warner Co. millinery;

- William S. Vent, 42, residence 805 Fairmount Avenue; vice president of Stronge & Warner Co. millinery; later president of Cook’s Taxicab & Transfer Co.;

- Augustus W. Ritzinger, 60, residence 661 Fairmount Avenue; vice president/treasurer of Robinson, Straus & Co. millinery; and

- William E. Davis, editor of the Twin City Commercial Bulletin, a weekly publication for St. Paul and Minneapolis wholesalers.7

Thursday and Friday mornings at the hotel, members discussed important business matters, such as the rising cost of freight, and the bother of customers who wanted to return goods. They devoted afternoons and evenings to amusement, camaraderie, and fine dining. Thursday evening, milliners attended a vaudeville program at the new Orpheum theater, at the northwest corner of Fifth and St. Peter Streets. Prior to their arrival in St. Paul, members had received an advance description of the convention. The description had hinted that “many of the delegates will be accompanied by ladies.” The vaudeville performance might have been considered inappropriate for ladies, as a review of the convention noted that “delegates attended the Orpheum theater,” while “ladies who had accompanied the delegates spent the evening at the [Metropolitan Opera House] where they enjoyed Henry Miller and Margaret Anglin in their delightful production of The Great Divide.” The entertainment committee for the convention had comprised St. Paul delegates Hugo Hirschman, Joseph Stronge, F. W. Lightner, A. W. Ritzinger, and Minneapolis delegate Dawson Bradshaw of Bradshaw Brothers millinery establishment. At the close of the vaudeville program, milliners crossed the street for a late supper at Carling’s Up-Town Café, at the northeast corner of Fifth and St. Peter Streets, where the banquet hall was “decorated profusely with ferns and American beauty roses, and each guest found at his place a white boutonniere.”8

Friday afternoon, members boarded two deluxe chartered streetcars, including the private streetcar of Thomas Lowry, president of the streetcar company. On a sightseeing journey to Minnetonka, they passed Como Park, the University of Minnesota, and the Minneapolis Chain of Lakes. At Minnetonka, they enjoyed a cruise on the steamer Hopkins, and they feasted in the elegant dining room of the Lafayette Club House. Friday evening, the group gathered for a sumptuous meal in the banquet room of Carling’s Up-Town Cafe.9

Feather Fire

Amid a fierce winter storm on Friday, January 29, 1909, a fire in downtown St. Paul threatened to destroy the city’s retail district, where M. Philipsborn Co. and other retailers specialized in women’s clothing and hats. The fire started at 7:30 p.m. from unknown causes, on the second floor of the four-story White House department store, on the northeast corner of Seventh and Cedar Streets. In a short time, flames burst through the roof, and the entire four floors collapsed.10

The St. Paul Daily News reported that fireman Michael Burns, of steam-powered Fire Engine No. 8, was severely burned while the engine company worked directly in front of the White House store. “His canvas coat repeatedly caught fire and was finally burned off his back.” With the help of firefighter Michael Mattocks, Burns rolled in a “water-filled gutter every few minutes to extinguish the flames.” The clothing of firefighter William Dunbar also caught fire, “but his stoker turned the hose on him before he had been badly burned.”11

Flames from the White House roared across Seventh Street and engulfed a three-story brick building occupied by the California Wine House, on the southeast corner of Seventh and Cedar Streets. James Mattocks, engineer of Engine No. 8, and coal-stoker John Ryan, were surrounded by flames and their clothing ignited. They too “threw themselves down in the running water a foot deep in the gutter and extinguished the flames.”12

Sub-zero temperatures, and winds blowing at forty-five miles per hour from the northeast, carried flames across Cedar Street from the White House, and destroyed the Fey Hotel, a five-story brick building on the northwest corner of Seventh and Cedar Streets. Horse-drawn Fire Truck No. 2, positioned between the White House and the Fey Hotel, was destroyed by flames. Heat from the burning truck was so intense that five nearby horses were injured when the hair was burned from their backs.13

The local newspaper reported that 274 firemen from nineteen engine companies battled the blaze. Firefighters included St. Paul Fire Chief J. J. Strapp and Assistant Fire Chiefs John Devlin, Myles McNalley, Edward Hein Jr., and Joseph Levagood. Hose Supply No. 5 of Minneapolis responded to a call for assistance from the St. Paul Fire Chief, and the horse-drawn Minneapolis equipment “made the long cold drive over Lake Street, to Marshall Avenue, down Nelson Avenue to Summit Avenue and thence down town [sic] in forty minutes.”14

Total damage in the city was estimated at more than $13 million in today’s dollars. Insurance fully covered the loss of the White House. At other businesses, not all losses were covered by insurance.

Feather Felons

The first week of August 1911, the owner of S. Weiss & Co. millinery store in downtown St. Paul received an alarming circular from a member of The Millinery Trade Review, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. The flier had been mailed to all Midwest members of the Millinery Jobbers Association and to “the chief of police in all of the larger cities.” It warned milliners and police officers to be on the lookout for an interstate thief who had robbed an Indianapolis, Indiana, wholesale milliner of “$1,000 worth of fine ostrich plumes” ($33,000 in today’s economy). The flier included a detailed description of the thief, who was thought to be 29-year-old John Lewis of Louisville, Kentucky:

“Lewis, which police believe to be an assumed name, is small in stature, probably five feet, three inches tall, a bit stout, weighing probably 160 pounds, has swarthy complexion, black hair and black eyes.”15

Late Saturday afternoon, August 12, Samuel Weiss spotted Lewis loitering at the store, located at 234 East Fourth Street. Weiss suspected that Lewis was casing the establishment in preparation for a nighttime robbery of ostrich plumes. Weiss phoned the Central police station, and plainclothes detective Frank Fraser, a twenty-year veteran of the police force, was immediately dispatched to the scene.16

When the store closed as usual at 5:00 p.m., Lewis left the store. Fraser followed him to Fourth and Wacouta Streets, where Lewis unexpectedly stepped aboard a westbound Selby-Lake streetcar. Fraser followed him onto the streetcar and apparently intended to quietly arrest the unsuspecting thief as the streetcar neared the Central police station, located only eight blocks away, along the streetcar route. He had no knowledge of Lewis’s true identity as Peter Juhl, a thief and a desperate armed escapee from the state prison at Stillwater, where he had served only five months of a nine-year sentence for robbery of a jewelry store owned by Harry Lunda at 119 Central Avenue in Minneapolis.17

As the streetcar approached the police station at Third and Market Streets, Fraser approached Juhl from behind “and placed his hands on [Juhl’s] shoulders, informing him he was under arrest.” Juhl “wheeled around, drawing a revolver from his hip pocket, and fired at the officer.” The bullet entered the officer’s abdomen and pierced several internal organs.18

The wounded detective grappled with Juhl and “tried to wrest the weapon from him. He called for help, but the passengers were panic-stricken, and as the [street]car had been stopped by the motorman (on Fourth Street between St. Peter and Market Streets), most of them made a hasty exit, some going out the windows, and others through the front and rear vestibules.”19

The commotion attracted the attention of 30-year-old St. Paul Police patrolman Michael Fallon (older brother of William H. Fallon, St. Paul mayor 1938-1940), who had been patrolling at Fourth and St. Peter Streets as the streetcar passed that intersection. He ran a half block toward Market Street and boarded the streetcar. According to St. Paul Police Historical Society records, Fallon clubbed Juhl on the head several times, knocking him unconscious.20

An ambulance carried Detective Fraser, age 48, to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he died of his wounds. Fallon dragged Juhl a half block along Fourth Street, to the Central police station, where records received from Stillwater State Prison revealed his criminal career as a diamond thief and a member of a gang of plume thieves, wanted for robberies in Cincinnati, Louisville, and Indianapolis, and for sale of stolen plumes in New York City.21

Peter Juhl, 29, pled guilty to murder in the first degree and received a life sentence at the state prison in Stillwater. However, for three years prior to his death in 1930, he had been a patient in a ward for the tubercular insane at St. Peter State Hospital.22

Feather Finale

Feather fashion fell from favor as social activists turned their attention to the protection of wildlife. The National Audubon Society established bird watching as a commendable pastime for genteel ladies, and the organization championed the efforts of conservationists and wildlife enthusiasts in a campaign against “the destructive fashion of feathers, which caused the deaths of millions of birds each year.”23 Prominent supporters included President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid outdoorsman and naturalist, and Dr. Frank Chapman, an ornithologist and bird curator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. In 1913, Congress enacted a law which placed all migratory birds under federal protection.24

In addition, and of equal importance in fads and fashion, a huge hat decorated with a flourish of feathers simply did not fit inside a compact Model “T” Ford. The practical affordable automobile had been introduced in 1908 and had gained rapid popularity. Soon, the enormous feathered hats faded from fashion, yet they remain in our collective memory as a symbol of fun and folly during the lives of our grandmothers or great-grandmothers.25

Janice Quick often wears a fanciful hat from her collection of fifty-five vintage hats. A few feature fluffy feathers from the breasts of domestic turkeys; none were made with ostrich feathers.

NOTES

- The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, College Edition (Random House, 1968), 848. The author still consults the dictionary she had been required to purchase for freshman English at the University of Minnesota in 1968. The term milliner was in common use at least by 1746 when French artist Francois Boucher created the oil painting The Milliner. Bernard Grun, The Timetables of History: A Horizontal Linkage of People and Events (Simon & Schuster, 1979), 345; Kathleen Rouser, “Heroes, Heroines and History: Who Went to the Millinery Shop?” http://www.hhhistory.com/2019/02/who-went-to-millinery -shop.html.

- Adee Braun, Lapham’s Quarterly, “Roundtable. Fine-Feathered Friends: A fashion craze begets animal activism”; http://americanhistory.si.edu/feather/ftfaex.htm. Rouser, “Heroes, Heroines and History.”

- Untitled document, http://americanhistory.si.edu/feather/ftfaex.htm.

- R. L. Polk & Co.’s St. Paul City Directory, 1908. The St. Paul Pioneer Press, May 17, 1908. Postcard “Mannheimer Bros., Dry Goods, St. Paul, Minn.,” postmarked 1913.

- R. L. Polk & Co.’s St. Paul City Directory, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911; U.S. Census, 1910. Besse M. Berkheimer obituary, The St. Paul Pioneer Press, February 22, 1951, 5. The name Besse was sometimes mistakenly spelled Bessie. The shop was later located at 370 St. Peter Street. Taxidermists in downtown St. Paul, as listed in R. L. Polk & Co.’s St. Paul City Directory, 1910, included Roy A. Heist, 20-1/2 East Seventh Street; Mentz B. Paasche, 26 East Third Street, 2nd floor; and Edes Robe Tanning Co. “Fur Dressers and Dyers, Furriers and Taxidermists,” 221 West Seventh Street.

- R. L. Polk & Co.’s St. Paul City Directory, 1908. The Millinery Trade Review, vol. 33, June 1908, 53-55. The Illustrated Milliner, April 1908, 26; June 1908, 30. Postcard: “Stronge & Warner Co., St. Paul, Minn.: Finest and Largest Wholesale Millinery Building in the World,” postmarked 1910. Postcard: “Jobbers Millinery Importers, Robinson Straus & Company,” postmarked 1926.

- Ibid. 53-55.

- Ibid. 53-55, 59, 63. “Orpheum” was the name of the production company; it might not have been the name of the building. The Millinery Trade Review, June 1908, 59, stated: “In the evening the delegates attended the Orpheum theatre in a body. This building is one of the new sights of St. Paul and is as beautiful as any building on the circuit. The delegates filled the best rows in the parquet and enjoyed a thoroughly good bill.” “Forget Merry Widow for Freight Rates,” The St. Paul Daily News, May 14, 1908, 5.

- The Millinery Trade Review, vol. 33, June 1908, 63-64.

- “Fire Exacts Heavy Toll from St. Paul: No Lives Are Lost,” The St. Paul Daily News, January 30, 1909, 1-2.

- “Fire Exacts Heavy Toll from St. Paul: Water Still Poured on Smoking Ruins,” The St. Paul Daily News, January 30, 1909, 2.

- “Fire Exacts Heavy Toll from St. Paul: No Lives Are Lost,” The St. Paul Daily News, January 30, 1909, 1-2.

- Ibid., 1-2.

- Ibid., 1-2. In this article, “Hein” was spelled “Hine,” and “Levagood” was spelled “Levigood.” R. L. Polk & Co.’s St. Paul City Directory, 1908.

- The Millinery Trade Review, vol. 36, July-December 1911, 436; “Detective Fraser Shot by Man He Arrested,” The St. Paul Pioneer Press-Dispatch, August 13, 1911, 1; “Fraser Victim of Desperado,” The St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 14, 1911, 11; Inflation calculator, officialdata.org. Minnesota death certificate 1930-MN-009299 records Juhl’s birthplace as Germany; “Funeral of Detective Fraser on Thursday,” The St. Paul Daily News, August 15, 1911, 1, reported that John Lewis, later identified as Peter Juhl, was born in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, and he arrived in the United States in 1904. John J. O’Connor, St. Paul police chief in 1911, “was the architect of the . . . agreement which guaranteed safe haven for ‘public enemies’ visiting St. Paul during the gangster era,” St. Paul Police Historical Society, http://www.spph.com/history/timeline.php. The average height of a 21-year-old male in the United States in 1912 was five feet, eight inches. https://ahundredyears ago.com. “Stealing from Import Cases,” The Millinery Trade Review, January 1908, 40.

- “Most Notorious: A True Crime History Podcast,” 2012, stated that Fraser had served as President Taft’s personal bodyguard during the president’s visit to St. Paul in 1910. www.mostnotorious.com/2012/11/07/the-murder-of-detective-frank-fraser.

- “Detective Fraser Shot on Car by Man He Arrested,” The St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 13, 1911, 1; “Detective Fraser Shot by Desperate Prisoner,” The St. Paul Daily News, August 13, 1911, 1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Detective Fraser Shot on Car by Man He Arrested,” The St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 13, 1911, 1; Jeff Neuberger, historian, and John J. DeNoma, Commander Retired, St. Paul Police Historical Society, letter to the author, 2016, and interview with the author, February 3, 2021. Minnesota death certificate 1911-MN-021420; Calvary Cemetery records.

- “Detective Fraser Shot on Car by Man He Arrested,” The St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 13, 1911, 1; Minnesota death certificate 1911-MN-021420, Frank Fraser.

- Minnesota death certificate 1930-MN-009299, Peter Juhl.

- Adee Braun, “Roundtable. Fine-Feathered Friends: A fashion craze begets animal activism,” Lapham’s Quarterly. www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/fine-feathered-friends.php.

- The National Audubon Society was founded in the United States in 1905. The Weeks-McLean Act was enacted in 1913; it was replaced by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918. “History of Audubon and Science-based Bird Conservation,” https://www.audubon.org/about/history-audubon-and-waterbird-conservation.

- Adee Braun, “Roundtable.” The author’s grandmother Charlotte “Ruth” Maurer (nee Thurston) (1887-1965) flaunted fanciful feathered hats, circa 1908-1911. As a St. Paul resident from 1944-1965, she enthusiastically purchased cosmopolitan hats in the millinery departments of the Golden Rule, Schuneman’s, Field-Schlick, and Dayton’s.

- Year

- 2025

- Volume

- 60

- Issue

- Number 2, Spring 2025

- Creators

- Janice R. Quick

- Topics