Selma 70 Exhibit

It was early in 1965 when Selma, Alabama, became the focus of Black voter registration efforts by Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). At the time, due to Jim Crow laws and voter suppression efforts, only 2% of eligible Black voters were registered in Selma. On February 18, white segregationists attacked a group of peaceful demonstrators in the nearby town of Marion. An Alabama state trooper fatally shot Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young African American demonstrator.

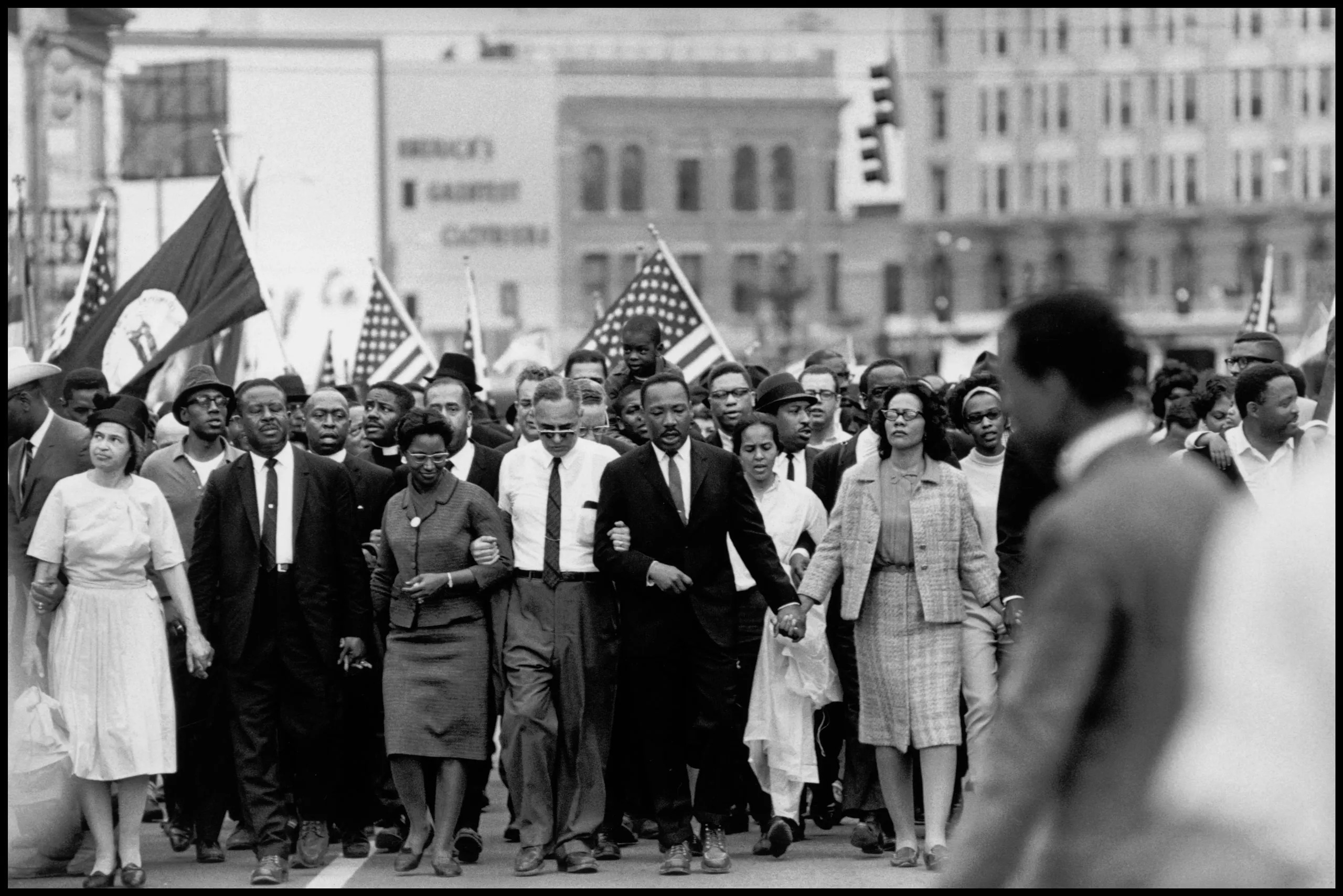

Led by the late Congressman John Lewis, who was then head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and fellow activist Hosea Williams, 600 marchers attempted to walk from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery on March 7. They were marching in protest of the killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson three weeks earlier. They were met with violent resistance. This event is now known as Bloody Sunday and precipitated several critical moments in the Civil Rights Movement.

Photo by Brice Davidson/Magnum (March 1965). [Source The New Yorker]

This exhibit shares some of the stories surrounding Selma, the Civil Rights Movement, and the experiences of the 70 Minnesota Pilgrims that traveled to Selma in 2015 to participate in the 50th Anniversary commemoration of this milestone in the Civil Rights Movement. Looking forward from that moment, our nation continues to grapple with racism and critical questions about the kind of society we want to leave to our descendants. Sharing your experiences through the interactive components of this exhibit can help others in our community learn and grow, we hope you will consider doing so.

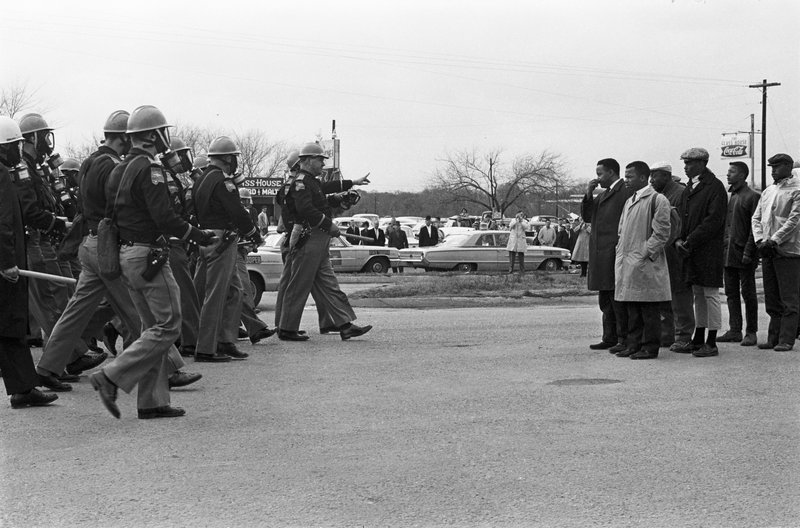

In Selma, Alabama, 600 marchers, led by John Lewis and civil rights activists, sought to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge towards Montgomery, advocating for African American voting rights. Their peaceful march was met with violent resistance.

Blocked by state troopers and police, the marchers were ordered to disband. Choosing to stand their ground, they faced tear gas and brutal beatings. The violence inflicted on the nonviolent protesters resulted in over fifty people being hospitalized.

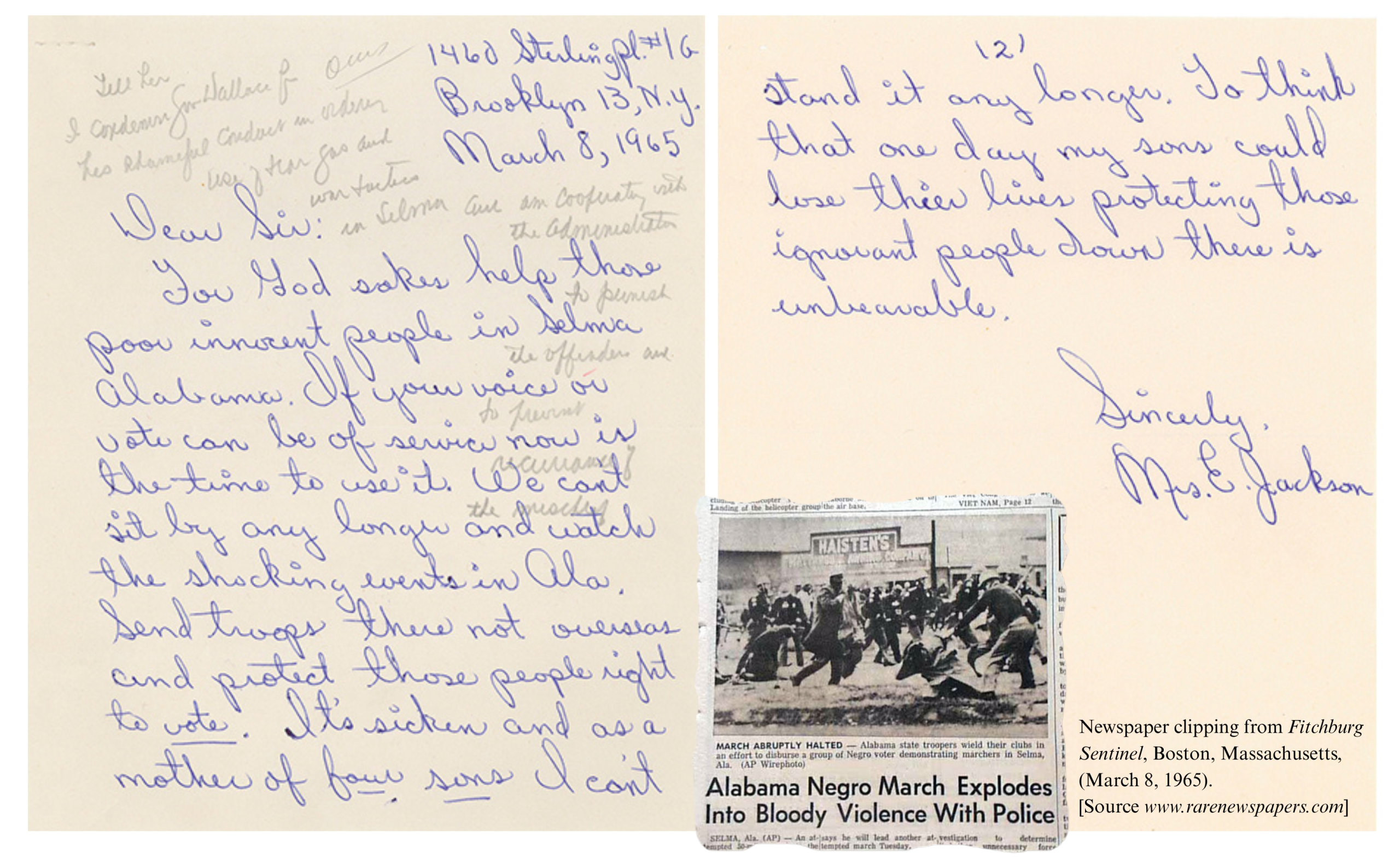

Letter from Mrs. E. Jackson (March 8, 1965). [Source National Archives]

Photo by Spider Martin (March 7, 1965). [Source The New Yorker]

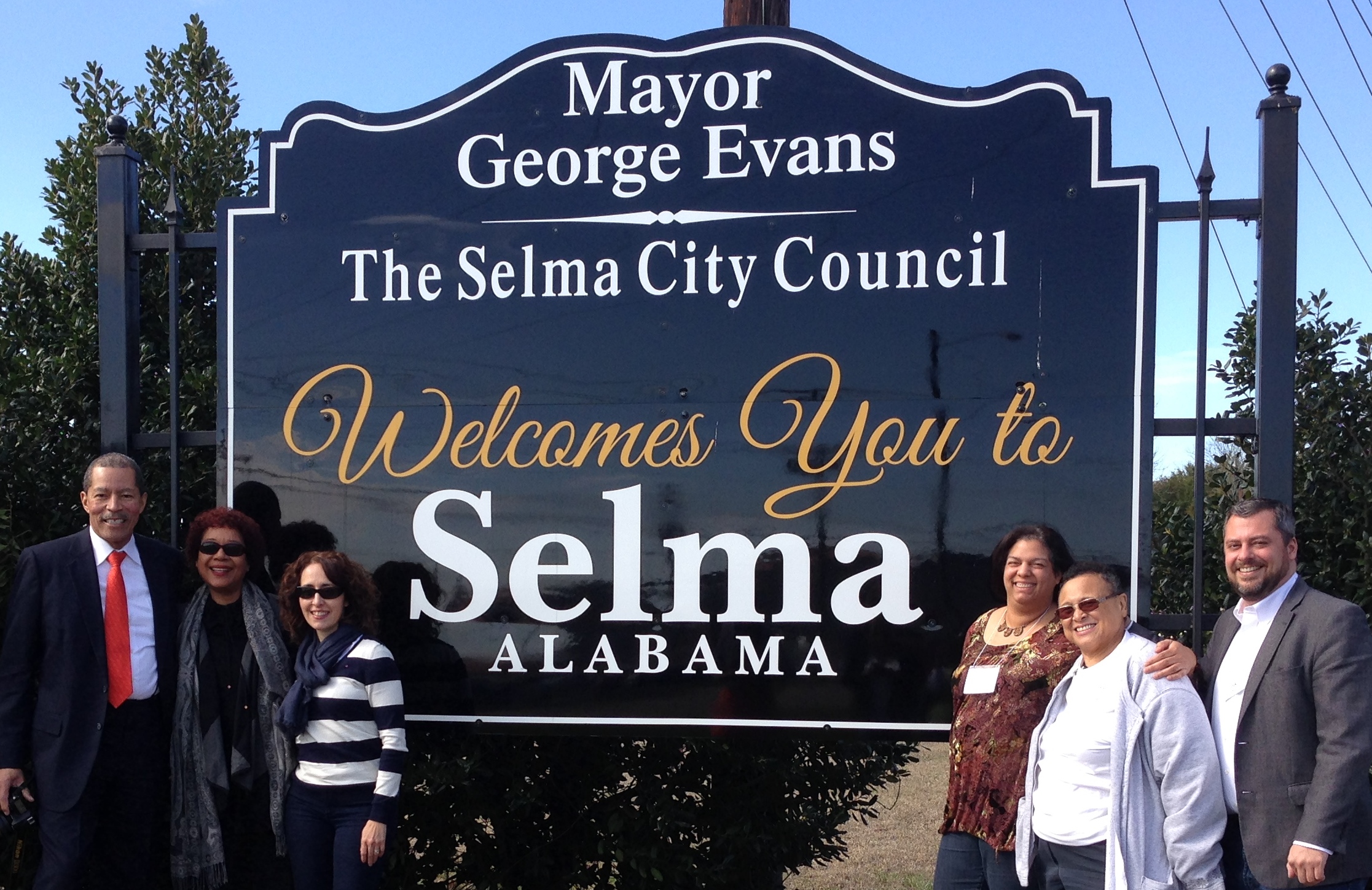

In 2015, to honor the 50th Anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” 70 people from Saint Paul, Minnesota, joined together for a powerful journey back to Selma, Alabama. They came from different walks of life, representing over a dozen local groups, all united by a common goal: to remember the past and inspire a future where equality reigns.

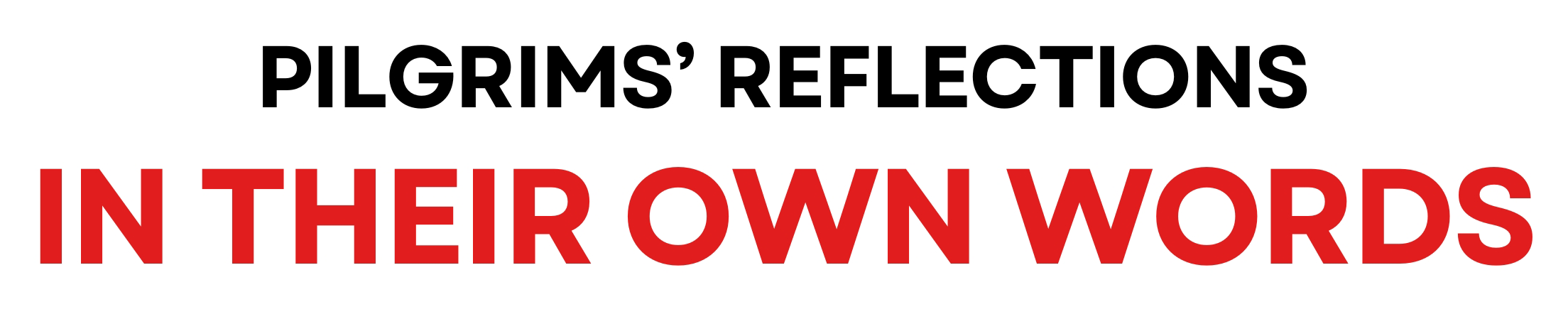

This diverse group included students, teachers, activists, and community leaders, each bringing their own story and perspective to the pilgrimage. Together, they retraced the steps of the brave marchers of 1965, crossing the very same Edmund Pettus Bridge in a symbolic act of remembrance and solidarity.

“We turned the corner on what may have been Main Street, and I could see the arches of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. On the giant ‘jumbotron’ screen, a video of Martin Luther King, Jr. could be seen and heard. It was surreal. We were walking the path of the 1965 protesters and Martin Luther King’s eloquence was inspiring us to fight for justice.”

-Vanne Owens Hayes, Pilgrim, from an article in Hennepin Lawyer magazine

“I’m not sure about my ability to make peace, but I do feel that the Selma Pilgrimage was so compelling I feel like I’ve been shot out of a cannon and am hurtling toward the infinite sky! I’m also pointed inward in ways that I’ve never experienced before, as well as back to my years living in Alabama in the 1960s.”

-Elaine Ambrose, Pilgrim

“We made the pilgrimage to Selma with great expectations to culminate in a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Members of our 70+ person delegation from the Twin Cities area came away with new knowledge and a stronger appreciation of the long and continuing struggle for civil rights.

Despite what we might have imagined, it was the steps backward—where we fell short of being in [the] right relationship with each other—that may have been our saving grace. These steps backward brought forth our resilience and made the next steps forward more solid and meaningful. By the final day, the relationships among our multi-racial band of travelers had moved to something much deeper; much more open, much more spiritual. We had begun to move from liking each other to loving each other.

It will be the continuation of the friendships built during this trip to Selma—and the intentional expansion of this circle to include more and more members of Unity [Unitarian Church] and the broader St. Paul community—that will make this trip to Selma really matter. These friendships have already led to more people getting involved in the local Black Lives Matter movement, more volunteers and support for Ujaama Place, more people stepping up to fight for voting rights for people with felony records, more commitment to the fight for racial justice.”

-Mary-Margaret Zindren, Pilgrim, from “Making Selma Matter”

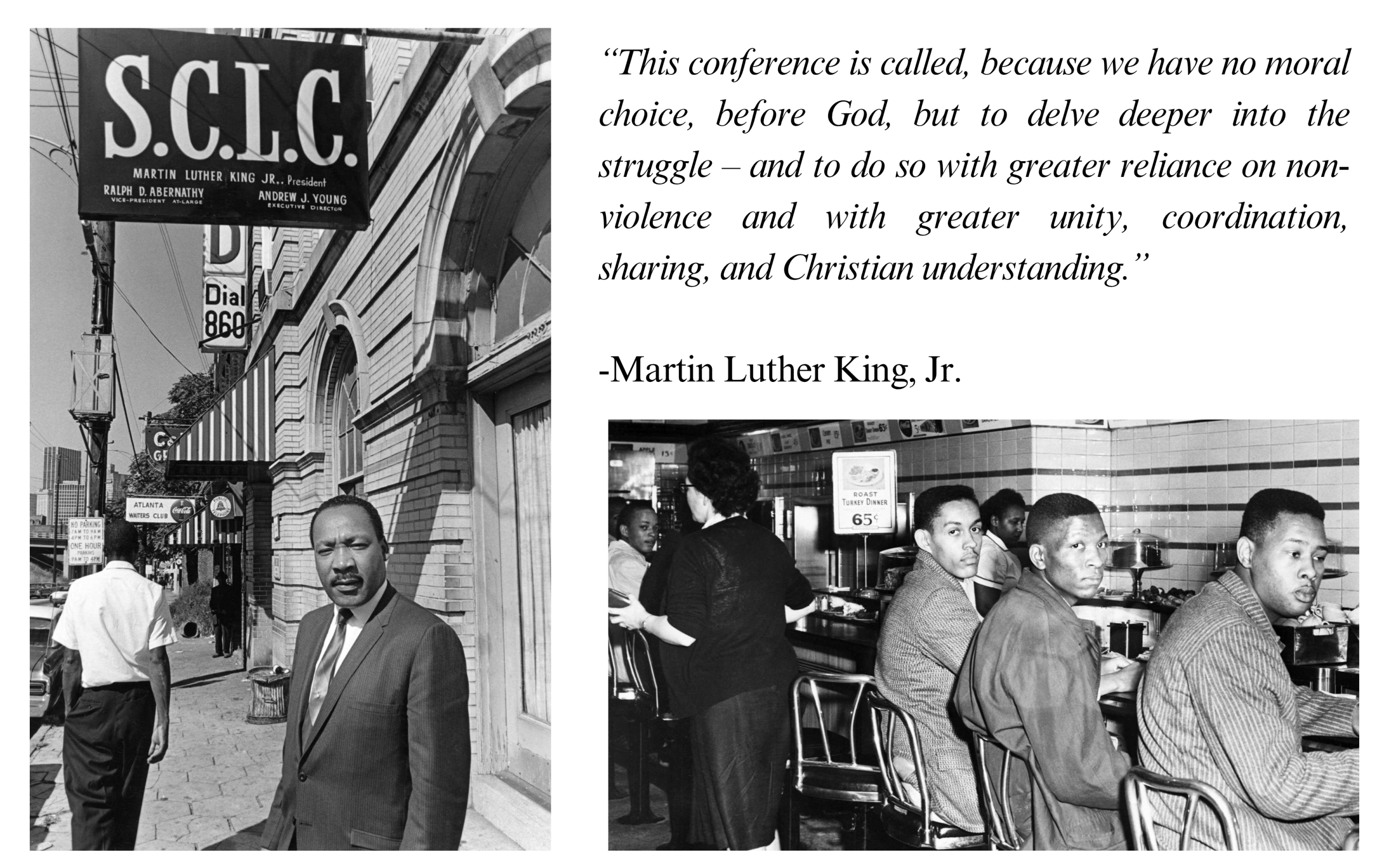

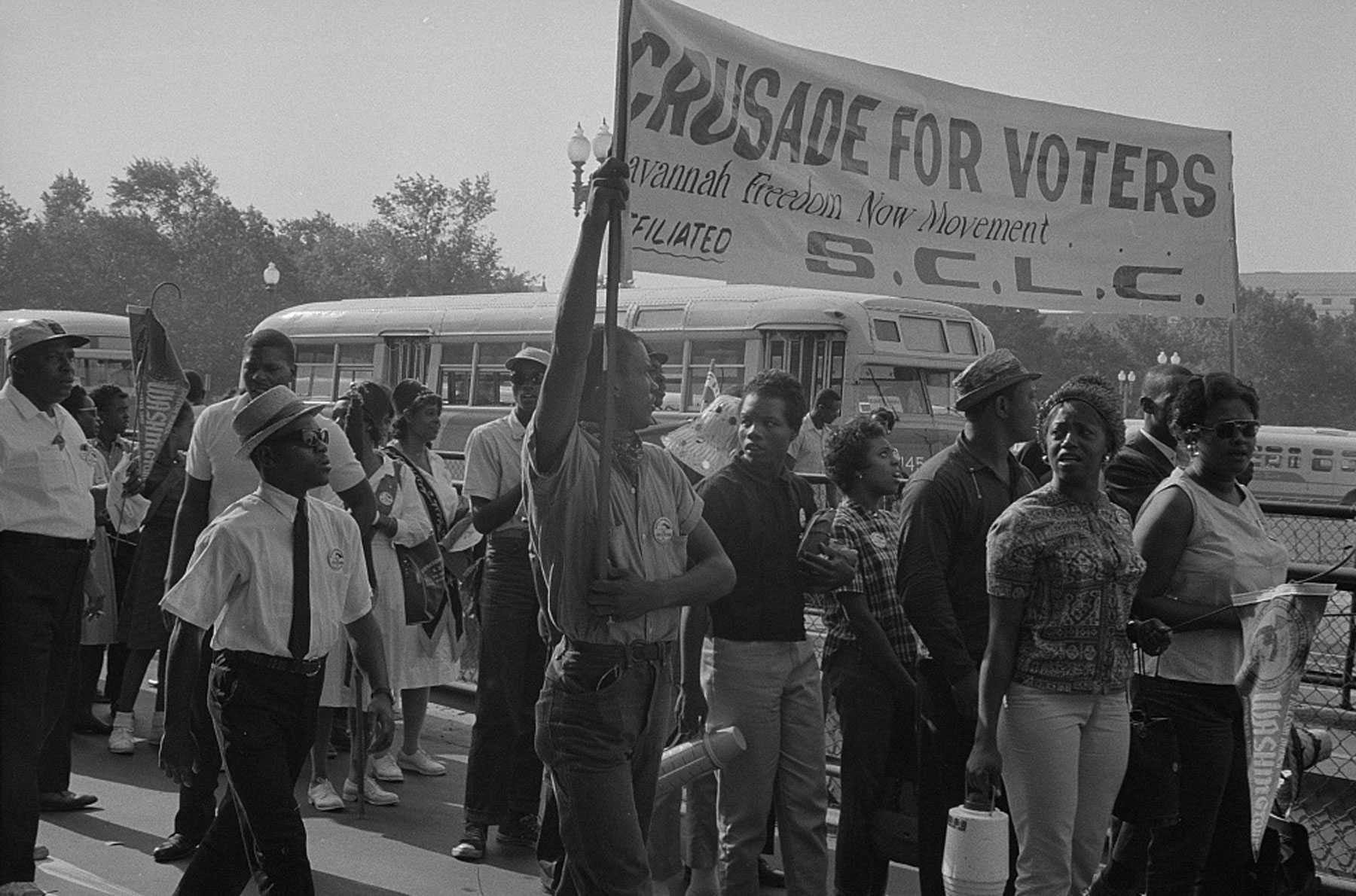

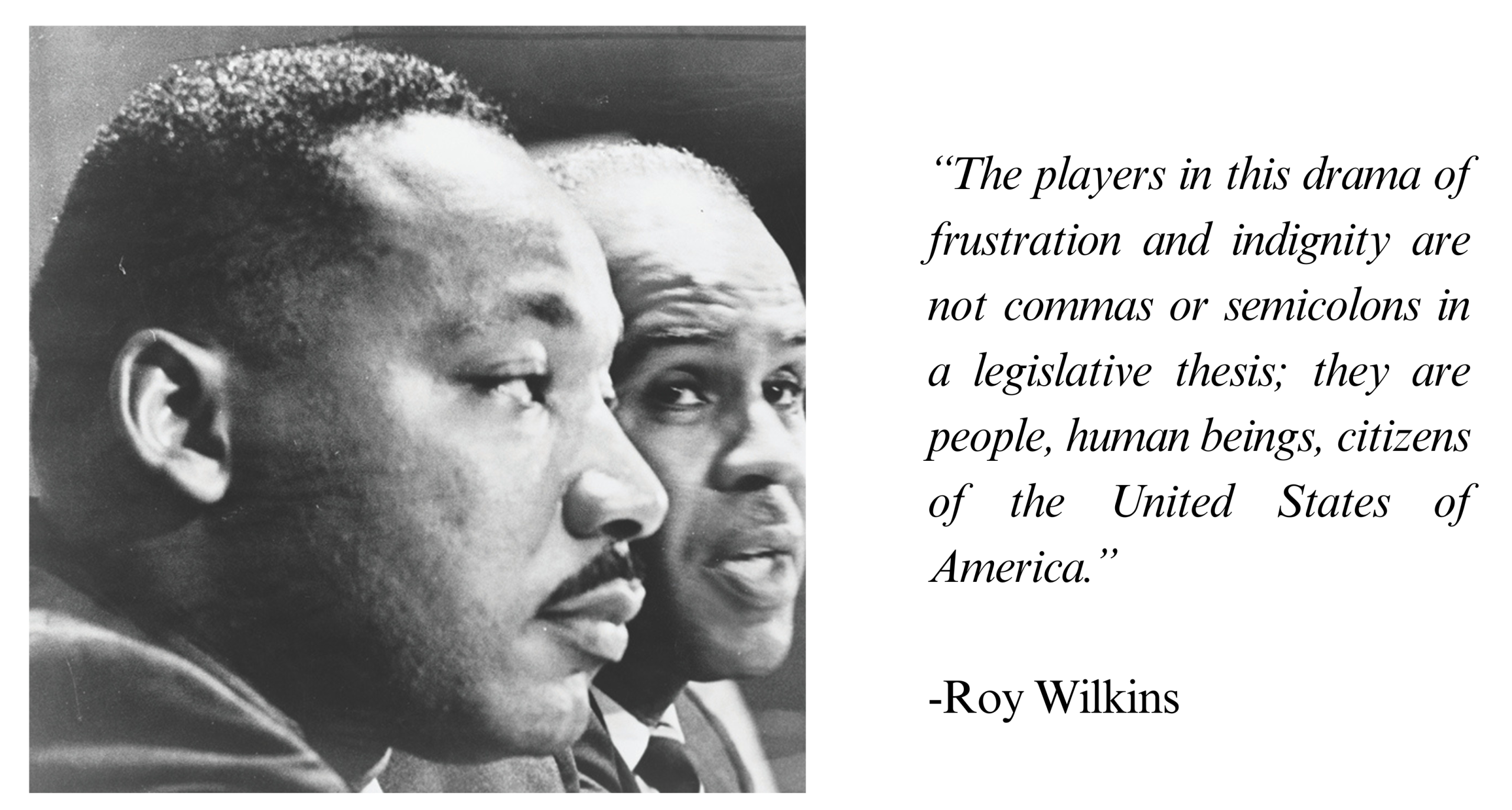

Organized in 1957, following the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, and led by Martin Luther King, Jr., SCLC was committed to nonviolent resistance. Unlike other organizations with similar goals, SCLC acted as an umbrella organization that supported local, affiliated organizations. It was tied closely to Black churches and they actively trained community members in their non-violence approach.

Photo by Benedict J. Fernandez (February 1968).

[Source National Gallery of Art]

Photo courtesy of the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

The SCLC is a nation-wide organization, today headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. Committed to non-violent action to achieve change, the organization continues to fight discrimination, police brutality, hate crimes, and racial profiling as it pursues social, economic, and political justice. More information at www.nationalsclc.org.

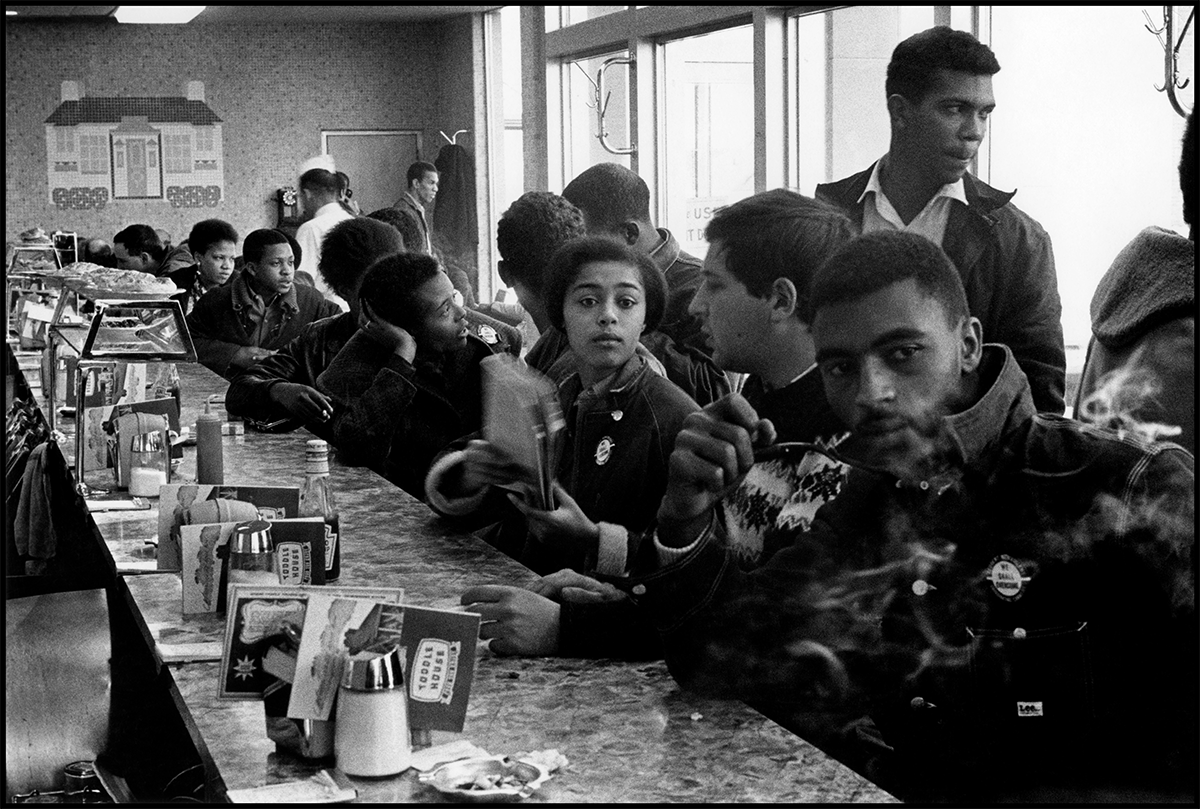

Founded in April 1960, SNCC focused on students taking direct action using nonviolent means. While aligned in its goals with the SCLC, it remained independent, and was sometimes at odds with fellow activist organizations.

By the time of the killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson in 1965, future congressmen John Lewis was the Chairman of SNCC. He would lead the non-violent marchers on that fateful day we now call “Bloody Sunday.” Lewis spent two days in the hospital having suffered a fractured skull after being beaten by Alabama State Troopers.

Photo by George Elfie Ballis (Date unknown). [Source Civil Rights Teaching]

Photo courtesy of the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

Members of SNCC would go on to start other civil rights organizations, most notably the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, a precursor to the Black Panther Party. Following “Bloody Sunday,” the organization started to move away from non-violence, alienating many of its supporters, and faded away by 1970.

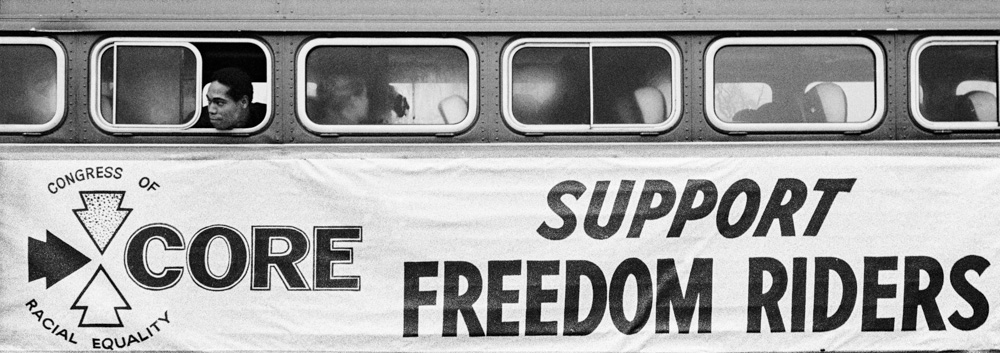

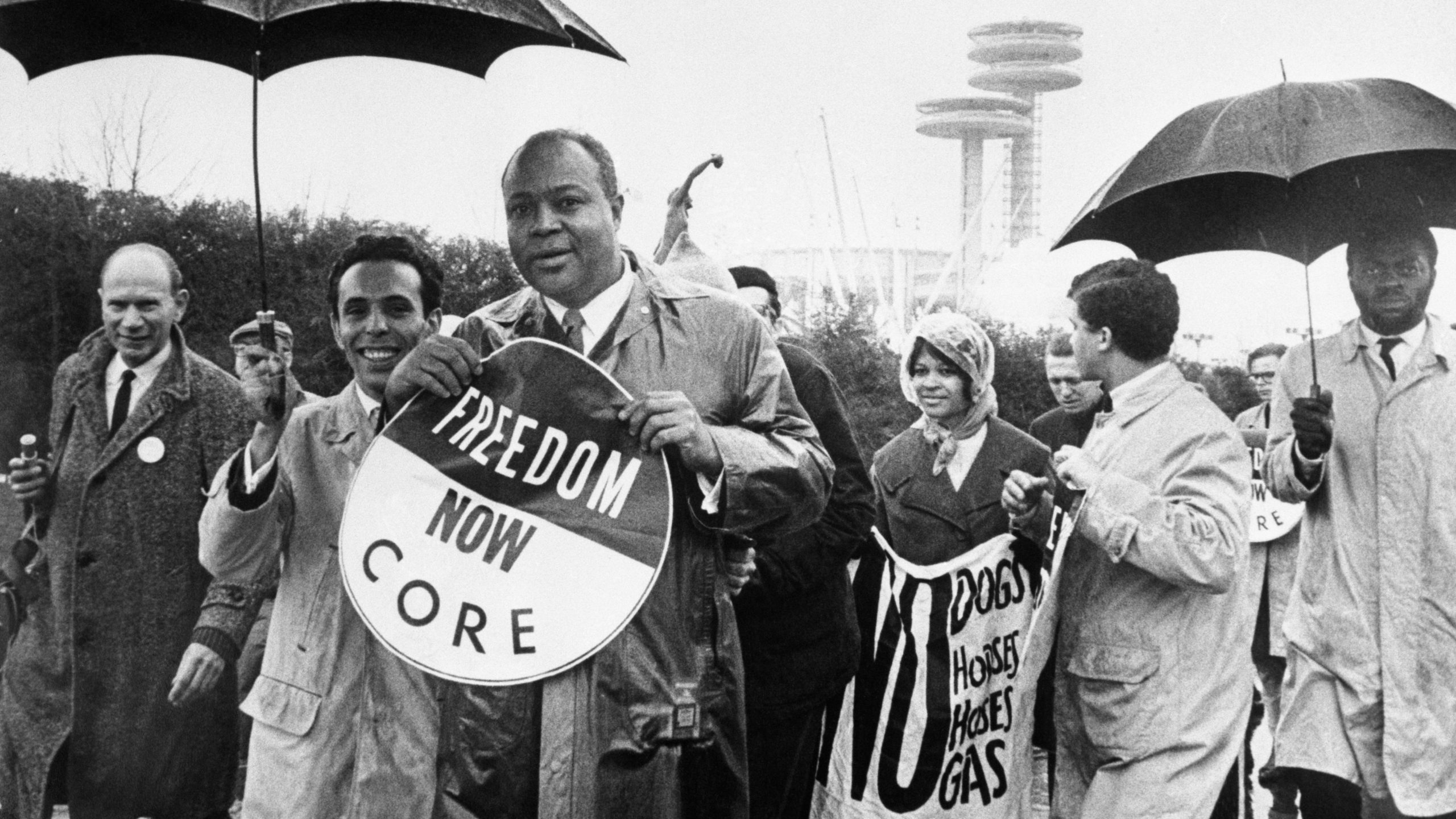

Founded in 1942 by students in Chicago, CORE was a leader in the development of non-violent direct action. In additions to sit-ins and other actions in Chicago, they organized the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, an integrated bus ride through the Upper South, meant to test whether or not Southern communities were complying with the 1946 Supreme Court ruling against segregation in interstate travel. They were not. While this effort did not attract the same kinds of violence later actions would, members of the group were jailed and harassed, with two members sentenced to serve on a chain gang in North Carolina.

CORE organized the more well-known Freedom Rides starting in 1961, which were met with far more violence. Departing from Washington D.C. on May 4, 1961, headed to New Orleans, two buses of Freedom Riders were harassed in Virginia and violently assaulted in South Carolina. On May 14 in Anniston, Alabama, a White mob of 100+ people firebombed one bus and assaulted the riders.

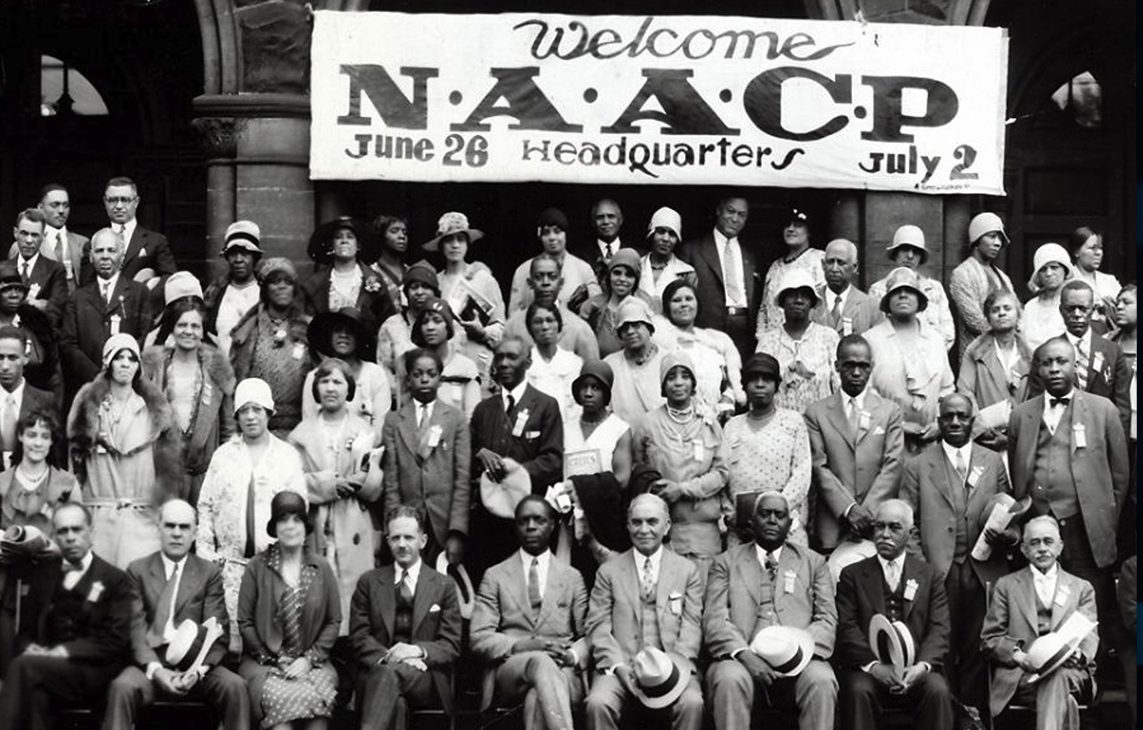

A deadly race riot in the city of Springfield, Illinois in 1908, set against a backdrop of lynchings and violence targeting African Americans, led to the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. On February 12, 1909, the nation’s largest and most widely-recognized civil rights organization was founded in New York City.

The NAACP was established to secure the rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Unlike SCLC, SNCC, and other direct-action organizations, the NAACP chose to focus much of its work within the legal and political systems of the time. They also provided legal assistance to the non-violent, direct-action activists that were frequently and unjustly jailed.

[Source NAACP]

Photo by Anonymous (1964). [Source New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper]

The NAACP still pursues its mission today: to achieve equity, political rights, and social inclusion by advancing policies and practices that expand human and civil rights, eliminate discrimination, and accelerate the well-being, education, and economic security of Black people and all persons of color. More information at www.naacp.org.

Photo by Stanley Wolfson (March 1965). [Source New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper]

• Housing: Racial disparities in homeownership persist despite anti-discrimination laws. In Minnesota, the Mapping Prejudice project has brought national attention to the practice of redlining and is an excellent resource for learning more about housing discrimination. More information at www.mappingprejudice.umn.edu.

• Employment: Workplace discrimination remains a battle for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Minnesota Department of Human Rights. More information at www.eeoc.gov/employees and www.mn.gov/mdhr.

• Voting Rights: Obstacles like gerrymandering and strict voter ID laws make it harder for minorities to vote. The American Civil Liberties Union, Take Action Minnesota, and League of Women Voters are all active organizations in this arena. More information at www.aclu-mn.org, www.takeactionminnesota.org, and www.lwvmn.org.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis Police in an incident captured on camera that touched off a summer of protests and riots around the world. Four police officers were convicted of Mr. Floyd’s murder.

The protests, called by many an uprising, followed several years of very visible killings of unarmed Black individuals by law enforcement, which garnered international attention. The uprising of 2020 catapulted organizations like Black Lives Matter onto the national stage and galvanized action by institutions and communities that had been largely ignoring the violence being perpetuated against Black citizens.

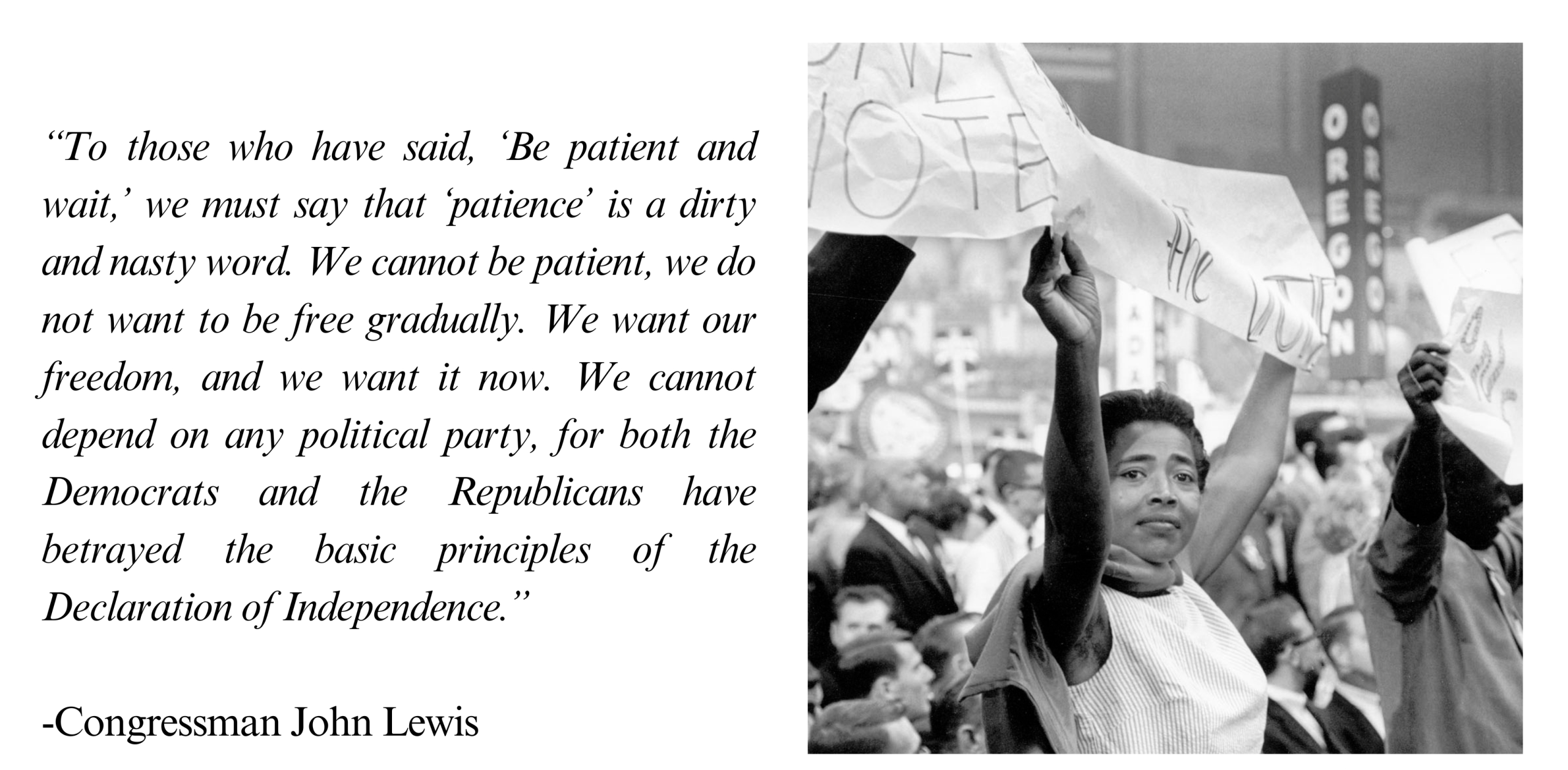

National Public Radio research released in 2021 identified 135 unarmed, Black individuals killed by police between 2015 and 2021. The data for this study showed a dramatically disproportionate level of violence directed against Black individuals. It also showed that significant repercussions for law enforcement in these cases were rare. Against this background of violence, some 60 years later, the sentiments expressed by the late Congressman John Lewis when he was the young chair of the SNCC in the 1960s seemed even more relevant:

“To those who have said, ‘Be patient and wait,’ we must say that ‘patience’ is a dirty and nasty word. We cannot be patient, we do not want to be free gradually. We want our freedom, and we want it now.”

As we reflect on the journey from Saint Paul to Selma and mark the now 60 years since “Bloody Sunday,” we invite you to share your experiences with racism and your thoughts on societal progress.

Share your story or express your hopes for a more inclusive and just world via the form below. All expressions shared will be collected by Ramsey County Historical Society and showcased in our collection. Your input adds to our understanding of how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go.

Selma 70 Reflections

Some organizations working to make our communities better have already been identified, here are a few more that are working towards positive change in our community, there are many more. These are some organizations that are making an impact in our community: