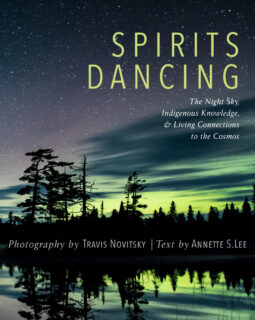

Spirits Dancing: The Night Sky, Indigenous Knowledge, & Living Connections to the Cosmos

- Year

- 2024

- Creators

- Reviewed by Meredith Cummings

- Topics

Spirits Dancing: The Night Sky, Indigenous Knowledge, & Living Connections to the Cosmos

Photography by Travis Novitsky; Text by Annette S. Lee

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2023

154 pages; paperback, 117 color illustrations, $19.95

“. . . my number one passion is making pictures of the night sky. I love photographing it, but I also love the simple act of being with it and experiencing it. The night sky is the anchor that keeps me grounded and centered.”[1]

These are personal notes of photographer Travis Novitsky, a member of the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. He collaborated with astrophysicist Annette S. Lee, a mixed-race Native American of Lakota, Chinese, and Irish ancestry, to create a stunning book—Spirits Dancing: The Night Sky, Indigenous Knowledge, & Loving Connections to the Cosmos.

Minnesotans who live in less-populated areas or who have the chance to escape the light pollution of the cities, may have gazed in awe at the starlit universe and witnessed the dancing lights of the aurora borealis across the far reaches of our northern state. It’s considered a “bucket-list experience,” as evidenced by night watchers on social media platforms desperate to witness the phenomenon, asking impatiently, Will ‘The Lady’ dance tonight? Can I see the lights with my own eyes, or do I need a camera? What if I travel three hours north and see nothing? The anticipation is palpable. The lack of knowledge about how an aurora works and the disappointment when the sky remains quiet is even more so.

That’s why this inviting book is a must. It will pique interest, but, more importantly, engage and teach readers about the aurora from three distinct perspectives—Western science, Indigenous beliefs and teachings, and anecdotes from the author and photographer.

The first captivating image is a silhouette of a being reaching toward a night sky blanketed with stars and the long, mystical path of the Milky Way. Readers will instinctively take a breath, slow down, and lose themselves in the beauty as Lee introduces readers to the concept of Etauptmumk (Two-Eyed Seeing). This idea helps us “. . . see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing . . .” and encourages us to “. . . use both eyes for the benefit of all.”[2]

Nearly every page provides a visual buffet. Novitsky gifts 120 images of the northern lights and a night sky bejeweled with stars through carefully curated galleries. But don’t think he instinctively senses the perfect location for a viewing, jumps in his car, snaps his shots, and captures the beauty of our universe just like that. Rather, he’s spent years hiking our state’s majestic woods and around its myriad lakes, envisioning opportunities where calm dark waters will mirror an exhibition in the sky, and silhouetted pines will “pop” in front of an illuminated backdrop. As a bonus, Novitsky reflects on the solitary hours spent communing with nature, his ancestors, and himself.

Praise, too, to Lee. In chapter two, she explains the science of the aurora and solar cycles, beginning with the history of early scientists who eventually answered the questions about which so many have wondered: What is the sun’s role in making an aurora come to life? How many colors can be seen, when, and why? Do the northern lights make noise? Can a sun storm cause problems at home? Do other planets experience auroras? This section can help readers better appreciate and understand the phenomenon before experiencing nature’s most impressive light show themselves.

Of course, Indigenous peoples have studied and connected with the night sky for millennia. In chapter three, Lee introduces earth/sky relationships of the Ojibwe, Dakota, and Lakota here in Mnísota Makhočhe along with the Ininew (Cree) in Canada, the Dene in the Northwest, and the Diné (Navajo) in the Southwest. For example, the Ojibwe teach that “[w]hen the soul departs, it travels a path to the west. . . . after other trials the soul comes to a great shining river, one whose reflection can be seen in the night sky . . . the Milky Way.” This serves as a pathway to transport the departed to ancestors in the great beyond. The Lakota believe babies are born with a wanáǧi or star spirit. At life’s end, the wanáǧi returns to the cup of the Big Dipper. And the Dene refer to the aurora borealis as éthen-kponé (reindeer fire)—“electric sparks escaping from the fur of the celestial white reindeers.”[3]

In this thorough book, Novitsky offers photography tips, including websites that track the solar flares that can spark an aurora. He also adds notes on every photograph—the camera used, the lens, the focal and exposure length, and more. Spirits Dancing concludes with an extensive source list and recommended readings for the curious.

Additional gifts offered here are personal stories that encourage readers to reflect. What can the sky teach us today—following a global pandemic, an escalating climate crisis, and the unknowns of technological innovation (or destruction)? Lee points to stillness; Novitsky to patience. Both invite readers to slow down, focus, and find clarity. Journey into nature’s night world, and just be. Maybe you’ll experience an aurora. Maybe you won’t, but you aren’t likely to be disappointed once you look up and witness the star-studded sky in its glory.

Meredith Cummings is editor of Ramsey County History magazine. She is a past editor of So It Goes: The Literary Journal of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library. She hopes to experience the majesty of the aurora borealis someday.

NOTES

[1] Travis Novitsky and Annette S. Lee, Spirits Dancing: The Night Sky, Indigenous Knowledge, & Living Connections to the Cosmos (St. Paul, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2023), 136.

[2] Novitsky and Lee, 2.

[3] Novitsky and Lee, 74, 76, 81-82.

- Year

- 2024

- Creators

- Reviewed by Meredith Cummings

- Topics