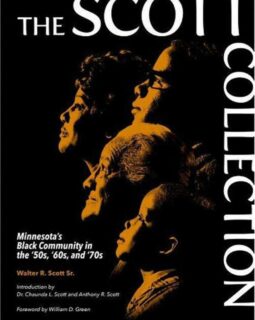

The Scott Collection: Minnesota’s Black Community in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s

- Year

- 2018

- Creators

- Reviewer: Earl Ross

- Topics

The Scott Collection: Minnesota’s Black Community in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s

Author: Walter R. Scott Sr.

Introduction by Anthony R. Scott; Preface by Chaunda L. Scott; Foreword by William D. Green

St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018

500 pages; softcover; 500 photos; $29.95

Published previously under separate titles, 1956, 1968, and 1976

Just over fifty years ago, the United States, indeed the world, seemed to be coming apart at the seams. That year, 1968, saw heightened student activism on college campuses against the Vietnam War, a more intense push for civil rights that spilled onto the streets, the Poor People’s Campaign for economic justice, the Fair Housing Act, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, to name just a few events that headlined the news. Here in the Twin Cities, an eleven-mile stretch between Minneapolis and St. Paul along Interstate 94 opened after ten years in the works, compressing the travel time and linking more directly Minnesota’s two largest cities into one large metropolitan center. This section of freeway was both a symbol of expanded opportunity and, sadly, of the disaggregation of neighborhoods like Rondo in St. Paul.

In this same year, an important and somewhat rare publication titled, Minneapolis Negro Profile: A Pictorial Resume of the Black Community, Its Achievements, and Its Immediate Goals, became available. Advertised as a book “for everyone who needs to know the truth about the Negro in Minneapolis,” Profile showcased the “inspiring successes achieved by the Black members of the Minneapolis community.” It featured employment biographies of the most prominent African Americans living and working in the city at the time as well as lesser-known individuals in the professional class. In its pages were doctors, lawyers, nurses, ministers, journalists, barbers, beauticians, athletes, educators, social service providers, and entertainers. For those lucky enough to own the original copy, Profile, like its companion books, Centennial Edition of the Minneapolis Beacon (1956) and Minnesota’s Black Community (1976) comprised the essential primary source of “Who’s Who” of African American Minnesotans working in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. Out of print for many years, these publications are now available in the eponymous single volume, The Scott Collection (2018).

Walter Scott, Sr., a journalist, editor, and publisher, produced the original volumes to raise awareness about the accomplishments of African American men and women in the region. He also hoped to inspire educational and career development among youth and to share the often hidden or untold stories about the contributions Black people have made to the state. Meticulously compiled, the subjects covered in each volume provide a window into the lives and activities of Black people during an era of great social change. Like community yearbooks, the trilogy operated as boosters for the Twin Cities black community at a time when many African Americans were relocating to the area to attend school and establish their careers. The profiles reflect not just the range of employment pursued by African Americans but the diversity of regions from which they came. It’s likely some newcomers to the area were introduced to the broader community through these publications.

The Scott Collection is divided into three sections of the unedited volumes with a new foreword from historian William D. Green and introductions by Chaunda and Anthony R. Scott. Chronologically arranged, the first volume focuses exclusively on Minneapolis in the 1950s. It is the shortest and most idiosyncratic of the three volumes. In the second volume, Profile, short overviews were added to the beginning of each chapter to provide context. Still focused primarily on Minneapolis, the 1960s’ publication expanded to include persons connected to the East Metro. However, for those seriously interested in St. Paul, the third volume, Minnesota’s Black Community, is where you want to start. St. Paul’s African American community features much more prominently. A bifold highlighting St. Paul’s Urban League stands out. References to Control Data Corporation, several African American churches, and persons working or living in St. Paul highlight the vibrancy of the Black community in the 1970s. That said, after reading such publications as Kate Cavett’s Voices of Rondo: Oral History of Saint Paul’s Historic Black Community (2005) and Days of Rondo by Evelyn Fairbanks (1990), one wishes Mr. Scott had completed a St. Paul edition of the Beacon and Profile that captured that city’s Black community in the two previous decades.

Another significant addition to the third volume includes a chapter devoted to Black women. Although women had always been featured in these volumes, starting with the very first publication, they never had a chapter of their own. By the 1970s, African American women had emerged as a critical mass entering the workforce. Their contributions to Minnesota are profiled in this new edition. They are powerful as an inspiration to all, but especially to children, then and now.

There is much to appreciate about this new publication. Perhaps the most exciting are the pages upon pages of pictures documenting the era. With nearly 2000 photos, The Scott Collection is one of the most extensive compilations of Black Minnesotans ever published. The photo portraits alone are a marvel and will assuredly have readers who worked or grew up in the Twin Cities during this period clamoring to identify earlier versions of themselves, parents, mentors, colleagues, and others. The real gems are the photos of everyday activities, men and women caught in motion doing various jobs. There are also photos of Black activism and of group shots from numerous social clubs. The images, more than the text (which may seem a bit dated in its language to some readers of today), reflect what Dr. Green writes in the foreword, “a most glorious legacy that was so easily overlooked.”

Earl Ross currently consults for the W. Haywood Burns Institute and The Annie E. Casey Foundation on juvenile justice reform and racial disparities. A passionate student of history, he often engages historical data in his work to better understand a community’s capacity for reform.

- Year

- 2018

- Creators

- Reviewer: Earl Ross

- Topics